Much has been said in the political arena about science. ‘We must follow the science’, many said (must we?). ‘Science, science, and science’, others said, without really knowing what they were talking about. But what are we talking about? After all, what is science?

George Edward Pelham Box (1919–2013) was a British statistician, one of the great statistical minds of the 20th century.

Karl Raimund Popper (1902-1994) was an Austro-British philosopher and professor.

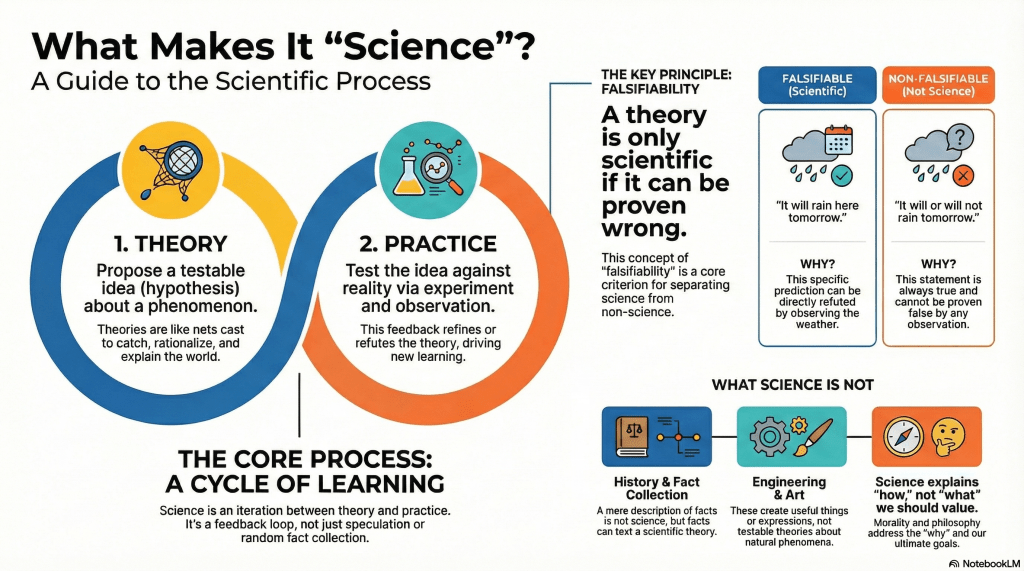

In 1976, GEP Box published an article entitled “Science and Statistics,” in which he conceptualized science:

Science is a means by which learning is achieved, not by mere theoretical speculation, on the one hand, nor by the undirected accumulation of practical facts, on the other, but rather by a motivated iteration between theory and practice, as illustrated in Figure A(1).

Figure A.

Author: G. E. P. Box.

Or, in other words, there are various forms of learning and knowledge acquisition (the end product of the learning process is acquired knowledge). Among them (I insist, there are several other valid forms) is the scientific process, or simply, science [in the strict sense].

Many people call what is called here science [or science in the strict sense] natural science and what is called here knowledge science. I will not adopt this nomenclature for a simple reason: its adoption is generally related to the attempt to give knowledge other than scientific knowledge (in the strict sense) an authority it lacks.

What characterizes the scientific process is the formulation of testable hypotheses about phenomena.

| Einstein and Eddington Einstein and Eddington is a British film that tells the story of how Sir Arthur Stanley Eddington (1882-1944) designed an experiment to test Albert Einstein’s (1879-1955) general theory of relativity, proposed in 1915. Eddington and astronomer Frank Watson Dyson organized two expeditions to observe the solar eclipse of 1919, to conduct the first test of Einstein’s theory: measuring the deflection (or lack thereof) of light by the Sun’s gravitational field. Worth watching. |

Hypotheses, models, conjectures, theories, or ideas are the product of the scientific process. Science always requires a hypothesis (or a model, or a conjecture, or a theory, or an idea) to explain a phenomenon.

A phenomenon is what is observed in nature, and can be a state or a transition between states. Science always requires a hypothesis (or a model, etc.) about a phenomenon.

Thus, knowledge that does not aim to explain a phenomenon is not a scientific theory.

A mere collection or description of facts is not science (therefore, history, fundamental knowledge for understanding the human condition, is not science).

Music theory is a knowledge of utmost human relevance, but it is not a science. If someone is interested in composing fugues, they can always turn to Johann Sebastian Bach’s “Art of Fugue.” However, composing music is not a pursuit of knowledge about a phenomenon.

The study of a country’s legal norms is not science.

However, it is possible to formulate a scientific theory of how revolutions occur and use historical facts to support such a theory (which can, for example, predict the conditions for the occurrence of a future revolution). Or to formulate a scientific theory about musical tastes or how jurisprudence is formed in light of certain norms.

Engineering knowledge is extremely rich and important. But engineering is also not a process of producing knowledge. It is a process of constructing utilities or improving utility-building processes for the benefit of people.

Furthermore, to construct such utilities, engineers often use scientific knowledge (in this case it is said that engineering used a technology), often not (in this case it is said that the engineering used a technique). Engineering knowledge should not be confused with science. Consider the construction of pyramids by the Egyptians, Greek temples, Roman aqueducts, and beautiful Gothic churches long before any knowledge that could be called science [in the strict sense] existed on such subjects.

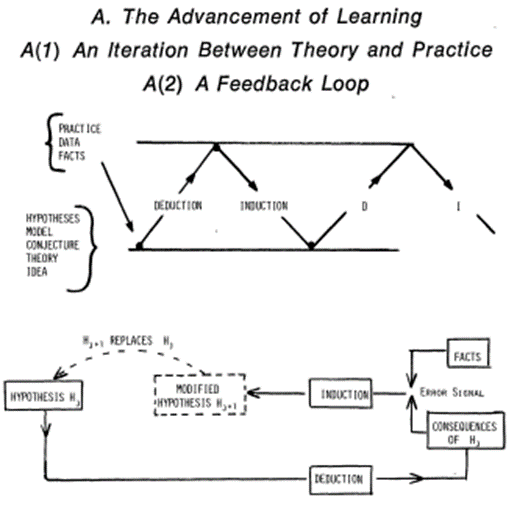

As a result of this concept of science, every scientific hypothesis must be falsifiable, a concept dear to K. Popper. That is, any hypothesis (etc.) must be capable of being compared with reality (with phenomena), and it can be verified whether the hypothesis reasonably explains the phenomenon (within reasonable accuracy).

If a hypothesis cannot be falsified (compared with reality), it is not scientific. The process of phasing a theory is done through what is called an experimental design.

Figure B.

Author: G. E. P. Box.

As already stated, science produces knowledge about phenomena. Therefore, science has much to say about how to achieve the ends we desire. We are talking here about phenomena and theories about phenomena (states – desired ends – and state transitions – how to get from where we are to where we want to be).

However, science does not have so much to say about what ends we should desire (why I should desire this end and not another). What are the limits we must respect and which we are not willing to violate to achieve our ends (our values). These are human choices in which religion, morality, and philosophy (non-scientific knowledge) can be much more relevant.

Selected texts

K. R. Popper. The Logic of Scientific Discovery. London: 1959.

A scientist, whether theorist or experimenter, puts forward statements, or systems of statements, and tests them step by step. In the field of the empirical sciences, more particularly, he constructs hypotheses, or systems of theories, and tests them against experience by observation and experiment.

(…)

According to the view that will be put forward here, the method of critically testing theories, and selecting them according to the results of tests, always proceeds on the following lines. From a new idea, put up tentatively, and not yet justified in any way—an anticipation, a hypothesis, a theoretical system, or what you will—conclusions are drawn by means of logical deduction. These conclusions are then compared with one another and with other relevant statements, so as to find what logical relations (such as equivalence, derivability, compatiblity, or incompatibility) exist between them.

(…)

But I shall certainly admit a system as empirical or scientific only if it is capable of being tested by experience. These considerations suggest that not the verifiability but the falsifiability of a system is to be taken as a criterion of demarcation. In other words: I shall not require of a scientific system that it shall be capable of being singled out, once and for all, in a positive sense; but I shall require that its logical form shall be such that it can be singled out, by means of empirical tests, in a negative sense: it must be possible for an empirical scientific system to be refuted by experience.

(Thus the statement, ‘It will rain or not rain here tomorrow’ will not be regarded as empirical, simply because it cannot be refuted; whereas the statement, ‘It will rain here tomorrow’ will be regarded as empirical.)

(…)

Two simple examples of methodological rules may be given. They will suffice to show that it would be hardly suitable to place an inquiry into method on the same level as a purely logical inquiry. (1) The game of science is, in principle, without end. He who decides one day that scientific statements do not call for any further test, and that they can be regarded as finally verified, retires from the game. (2) Once a hypothesis has been proposed and tested, and has proved its mettle, it may not be allowed to drop out without ‘good reason’. A ‘good reason’ may be, for instance: replacement of the hypothesis by another which is better testable; or the falsification of one of the consequences of the hypothesis. (The concept ‘better testable’ will later be analysed more fully.) These two examples show what methodological rules look like. Clearly they are very different from the rules usually called ‘logical’. Although logic may perhaps set up criteria for deciding whether a statement is testable, it certainly is not concerned with the question whether anyone exerts himself to test it.

(…)

Scientific theories are universal statements. Like all linguistic representations they are systems of signs or symbols. Thus I do not think it helpful to express the difference between universal theories and singular statements by saying that the latter are ‘concrete’ whereas theories are merely symbolic formulae or symbolic schemata; for exactly the same may be said of even the most ‘concrete’ statements.

Theories are nets cast to catch what we call ‘the world’: to rationalize, to explain, and to master it. We endeavour to make the mesh ever finer and finer

(…)

To give a causal explanation of an event means to deduce a statement which describes it, using as premises of the deduction one or more universal laws, together with certain singular statements, the initial conditions. For example, we can say that we have given a causal explanation of the breaking of a certain piece of thread if we have found that the thread has a tensile strength of 1 lb. and that a weight of 2 lbs. was put on it. If we analyse this causal explanation we shall find several constituent parts. On the one hand there is the hypothesis: ‘Whenever a thread is loaded with a weight exceeding that which characterizes the tensile strength of the thread, then it will break’; a statement which has the character of a universal law of nature. On the other hand we have singular statements (in this case two) which apply only to the specific event in question: ‘The weight characteristic for this thread is 1 lb.’, and ‘The weight put on this thread was 2 lbs

We have thus two different kinds of statement, both of which are necessary ingredients of a complete causal explanation. They are (1) universal statements, i.e. hypotheses of the character of natural laws, and (2) singular statements, which apply to the specific event in question and which I shall call ‘initial conditions’. It is from universal statements in conjunction with initial conditions that we deduce the singular statement, ‘This thread will break’. We call this statement a specific or singular prediction*

The initial conditions describe what is usually called the ‘cause’ of the event in question. (The fact that a load of 2 lbs. was put on a thread with a tensile strength of 1 lb. was the ‘cause’ of its breaking.) And the prediction describes what is usually called the ‘effect’. Both these terms I shall avoid. In physics the use of the expression ‘causal explanation’ is restricted as a rule to the special case in which the universal laws have the form of laws of ‘action by contact’; or more precisely, of action at a vanishing distance, expressed by differential equations. This restriction will not be assumed here. Furthermore, I shall not make any general assertion as to the universal applicability of this deductive method of theoretical explanation. Thus I shall not assert any ‘principle of causality’ (or ‘principle of universal causation’). The ‘principle of causality’ is the assertion that any event whatsoever can be causally explained—that it can be deductively predicted. According to the way in which one interprets the word ‘can’ in this assertion, it will be either tautological (analytic), or else an assertion about reality (synthetic). For if ‘can’ means that it is always logically possible to construct a causal explanation, then the assertion is tautological, since for any prediction whatsoever we can always find universal statements and initial conditions from which the prediction is derivable. (Whether these universal statements have been tested and corroborated in other cases is of course quite a different question.) If, however, ‘can’ is meant to signify that the world is governed by strict laws, that it is so constructed that every specific event is an instance of a universal regularity or law, then the assertion is admittedly synthetic. But in this case it is not falsifiable, as will be seen later, in section 78. I shall, therefore, neither adopt nor reject the ‘principle of causality’; I shall be content simply to exclude it, as ‘metaphysical’, from the sphere of science.

(…)

Questions for reflection

- What can we say about a politician who, in order to secure approval of a legislative measure that restricts citizens’ rights, argues that we should follow science?

Leave a comment