All models are wrong, but some are useful.

George E.P. Box

Although the history of political ideas is always receiving new contributions, it is observed that most of them are related to certain fairly characteristic political mentalities, related to the way people see aspects of life – such as religiosity, moral issues or even the meaning of existence -, economic issues, politics (such as what is law and justice) and power relations, among other aspects.

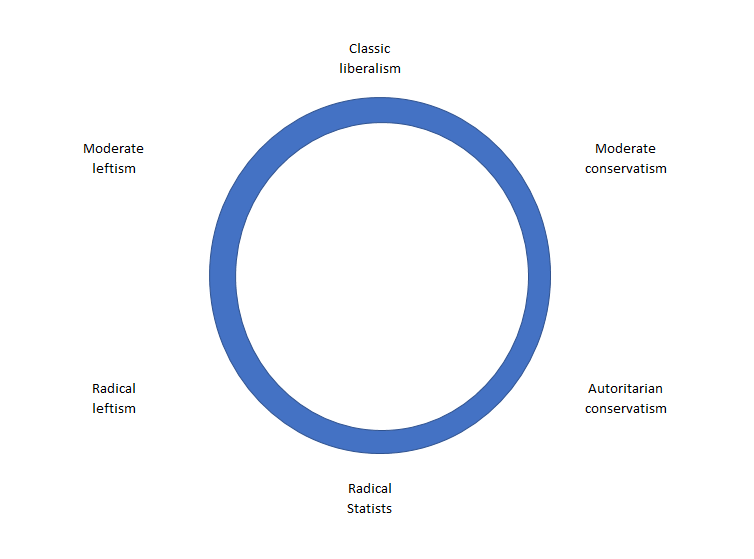

To facilitate the understanding of these ideals, in this book we classify political mentalities into six groups, using a circular diagram: classical liberals, moderate conservatives, authoritarian conservatives, radical statists, radical leftists and democratic leftists. The ideals (or political ideologies) are related to these six groups.

Figure 1: The basic scheme of the circular diagram of political mentalities

This model suggests that political ideals (or ideologies) are not adequately represented in a straight line, but rather relate to mindsets organized in a circle where adjacent groups share ideas and characteristics, while opposing groups are fundamentally opposed, representing fundamental conflicts.

Furthermore, the proposed circular diagram aligns with existing discussions in political science about non-linear models of political ideologies. Traditionally, political spectra are linear, with the left (e.g., socialism) opposite the right (e.g., conservatism). However, a circular model of mindsets seems to better explain where extreme ideologies, such as communism (a type of radical extremism) and fascism (a type of radical statism), share totalitarian tendencies, positioned adjacently. This challenges the linear model’s diametric opposition assumption and supports the idea of a circle where ideologies blend at the edges. Furthermore, unlike the horseshoe theory, which twists the straight line and only brings the extremes closer together, the circular diagram suggests how all mentalities connect, forming a fluid continuum. It is important to note that the diagram is a simplified representation of reality (like all models), since people’s real beliefs (like my own) often mix elements from several groups. Still, it is useful in helping to understand political ideas and even the reality of political dynamics. Note that the names given to the groups do not correspond to the names of political parties or groups. In fact, the six groups indicated refer to the mentality of the people in these groups, who may or may not be organized into parties or other forms of political grouping (such as non-governmental organizations, for example). Often, distinct political groups can be grouped into a single mentality that shares common elements. This continuum between mentalities makes it easier to understand, for example, how Benito Mussolini (originally a socialist, a radical leftist), as well as many other socialists, became a fascist (one of the groups classified as radical statists) during and after the First World War; in the same way that authoritarian conservatives (such as the traditionalist Francisco Franco) followed the opposite path to often become almost indistinguishable from radical statists.

Or how Friedrick Hayek (Nobel Prize in Economics in 1974) went from a moderate leftist (during the First World War) to a pro-market classical liberalism (after the First World War) and a great defender of the natural order (a concept so dear to moderate conservatism).

Although people evolve and change their political positions (after all, some people learn something from experience), transitions to similar mentalities (gradually) are much simpler and more common (although radical changes occur for some people).

Furthermore, throughout the texts to be studied, we will see how new and other ideas fit into or evolved from these categories without losing the central elements of these mentalities.

Leave a comment