Historical and Biographical Context

Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274), a medieval Dominican, is a central figure in political philosophy, known for integrating Aristotelian philosophy with Christian theology.

In his Summa Theologica (1265-1273), he addresses the nature of law, ethics, and governance. His vision reflects the mindset that Christian morality should guide state action, characterizing him as a traditionalist conservative (which we classify as an authoritarian conservative, very close to the moderates), but whose ideals influenced authoritarian and moderate conservative thinkers, and even classical liberals.

Figure 9. Saint Thomas Aquinas.

Autor: Bartolomé Esteban Murillo (1617-1682)

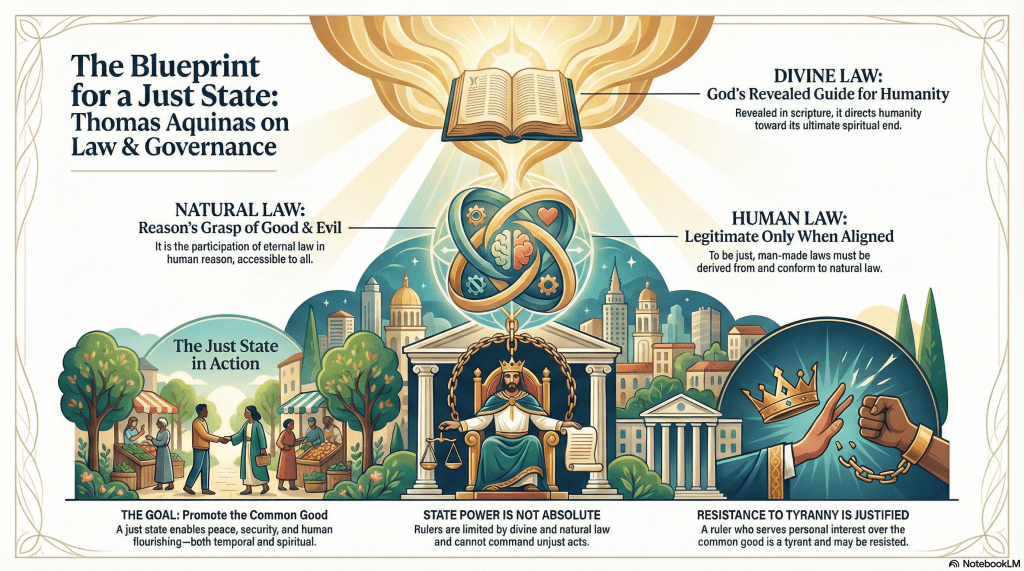

Concept of Divine Law

Aquinas defines divine law as revealed by God, primarily through the Bible.

He distinguishes the law of the Old Testament (e.g., the Ten Commandments) from the New Testament (e.g., the Gospels), considering the former imperfect, external, and based on fear, a mere preparation for the latter, considered perfect, internal, and based on love and charity.

The Old Law prepared the way for Christ, acting as a “pedagogue” (Galatians 3:24), with its temporary ceremonial and judicial precepts, while the moral ones remain.

The New Law justifies directly through Christ, explaining the true meaning of the ancient precepts and adding counsels of perfection (“justification”, for Aquinas, refers to the theological process by which a sinner is transformed from a state of sin and separation from God into a state of righteousness, or justice, and friendship with God). This law is part of the eternal law, the divine wisdom governing the universe, but directed to humans to guide them to salvation.

Table. Distinctions between the Old Testament and the New Testament law

| Aspect | Old Testament Law | New Testament Law |

| End | Submission to God, but imperfect, based on fear | Same end, but perfect, based on charity (caritas in Latin, meaning divine love or agape) |

| Nature | Imperfect, external, as a pedagogue, focused on external acts | Perfect, internal, focused on internal disposition, law of love |

| Grace: | Did not bestow the Holy Spirit in a manner that directly infuses and spreads divine love into the hearts of believers as a general or intrinsic effect of the Law itself, though some did receive it (such as the patriarchs and the prophets). | His higher nature derives its preeminence from spiritual grace, spreading charity in hearts |

| Precepts | Moral, ceremonial, and judicial, many external acts (e.g., circumcision) | Fewer additional precepts, focused on moral and sacramental precepts (e.g., Eucharist) |

| Fulfillment | Prefigured justification, ceremonials as shadows | Fulfills the Old, justifies by Christ, explains true meaning |

| Burden | Heavier due to ceremonies, external, easier without virtue | Lighter, internal, difficult without virtue, but lightened by love |

| Containment | Contains the New Law virtually, as a seed | Explicitly states the implicit, e.g., faith |

The divine law is complemented by natural law, the participation of eternal law in human reason, allowing human beings to discern good and evil.

In political terms, human laws must align with natural and divine law to be legitimate, reflecting universal moral principles. For example, in the Summa Theologica (ST I-II q. 90 a. 2), he argues that law “is nothing more than an ordinance of reason for the common good, promulgated by the head of the community,” guided by divine reason.

The Common Good as a Goal

The common good, for Aquinas, is the ultimate end of the political community. This includes peace, justice, security, and conditions for human flourishing, encompassing both temporal and spiritual goods, since the ultimate end is God. The state, as a “complete community,” must promote this, but is limited by moral norms derived from divine law, such as not killing innocents, not lying, or not engaging in extramarital sex. These limitations ensure that state actions align with the common good, promoting virtue, especially justice, but without coercively imposing private virtues beyond the public, such as a relationship with God.

| Marco Rubio on promoting the common good. Marco Antonio Rubio (1971) is an American politician and lawyer, currently serving as the United States Secretary of State. In his opening remarks before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee on January 15, 2025, he mentioned that he was called, as Secretary of State, to promote the common good: I also want to acknowledge all the blessings that God has bestowed upon me in my life. My faith is critical and it’s something I will lean and rely on heavily in the months that are ahead. In a tumultuous world where my faith – we are called to promote the cause of peace and the common good, and that task has gotten harder than it’s ever been. And I will rely heavily on my faith and pray for God’s blessings, that he’ll provide me the strength, the wisdom, and the courage to do what is right in these tenuous moments. (The full speech can be read at https://www.state.gov/opening-remarks-by-secretary-of-state-designate-marco-rubio-before-the-senate-foreign-relations-committee) |

Relationship Between Divine Law and State Action

Aquinas argues that divine law should guide the state because the common good includes the spiritual end of citizens. Rulers have a duty to promote virtue, but recognize limits, such as not coercively imposing faith, respecting religious freedom.

In the Summa Theologica (ST I-II q. 98 a. 1, q. 100 a. 2), he limits the state’s coercive jurisdiction to external acts affecting the public good, not private morality beyond justice. In cases of conflict, human laws contrary to divine law are not true laws, and citizens are not obliged to obey them.

Furthermore, he considers laws that serve only the ruler’s interests to be tyrannical, a “perversion of the law” (ST I-II q. 92 a. 1 ad 4 & 5; II-II q. 69 a. 4). In this context, he justifies resistance and, in extreme cases, the deposition of tyrants, as long as there is a public authority to assume the common good, although he prefers passive disobedience due to possible collateral damage (ST II-II q. 42 a. 2 ad 3, q. 104 a. 6 ad 3).

Contemporary Relevance

Although his vision is deeply theological, his principles, such as the primacy of the common good, moral limitations on state power, and the right to resist tyranny, resonate in modern debates across the political right, especially among traditionalist conservatives.

Summary Table: Key Ideas of Thomas Aquinas

| Concept | Description |

| Divine Law | Revealed by God, guide to salvation, complements natural law. |

| Natural Law: | Participation of eternal law in human reason, basis for just laws. |

| Common Good: | Social conditions for human flourishing, includes temporal and spiritual goods. |

| Limitations of the State: | Must follow moral norms (e.g., not kill innocents) and avoid tyranny. |

| Resistance to Tyranny: | Justified if there is public authority to assume the common good, preference for passive disobedience. |

Conclusion

Thomas Aquinas proposed that divine law should guide state action to seek the common good, integrating faith and reason. His philosophy, rooted in Christian theology, emphasizes moral limits to state power and justifies resistance to tyranny, positioning itself between Authoritarian Conservatives and Moderates. Despite controversies in secular contexts, his ideas remain relevant, especially in debates about religion and the state, reflecting their lasting influence on political philosophy.

Key Points

- The Law of Love, in the New Testament, is the divine law par excellence, having supplanted the imperfect laws of the Old Testament, which virtually contain the New Law as a seed.

- Divine law should guide state actions to achieve the common good, emphasizing moral and spiritual flourishing.

- Resistance to tyrannical rulers who prioritize personal interests over the common good is justifiable, advocating a balance between order and freedom.

Selected Texts

Thomas Aquinas. Summa Theologiae. https://www.newadvent.org/summa/

Question 93. The eternal law

- What is the eternal law?

- Is it known to all?

- Is every law is derived from it?

- Are necessary things subject to the eternal law?

- Are natural contingencies subject to the eternal law?

- Are all human things subject to it?

Article 1. Whether the eternal law is a sovereign type [ratio] existing in God?

(…)

I answer that, Just as in every artificer there pre-exists a type of the things that are made by his art, so too in every governor there must pre-exist the type of the order of those things that are to be done by those who are subject to his government. And just as the type of the things yet to be made by an art is called the art or exemplar of the products of that art, so too the type in him who governs the acts of his subjects, bears the character of a law, provided the other conditions be present which we have mentioned above (Article 90). Now God, by His wisdom, is the Creator of all things in relation to which He stands as the artificer to the products of his art, as stated in the I:14:8. Moreover He governs all the acts and movements that are to be found in each single creature, as was also stated in the I:103:5. Wherefore as the type of the Divine Wisdom, inasmuch as by It all things are created, has the character of art, exemplar or idea; so the type of Divine Wisdom, as moving all things to their due end, bears the character of law. Accordingly the eternal law is nothing else than the type of Divine Wisdom, as directing all actions and movements.

(…)

Article 3. Whether every law is derived from the eternal law?

(…)

I answer that, As stated above (Question 90, Articles 1 and 2), the law denotes a kind of plan directing acts towards an end. Now wherever there are movers ordained to one another, the power of the second mover must needs be derived from the power of the first mover; since the second mover does not move except in so far as it is moved by the first. Wherefore we observe the same in all those who govern, so that the plan of government is derived by secondary governors from the governor in chief; thus the plan of what is to be done in a state flows from the king’s command to his inferior administrators: and again in things of art the plan of whatever is to be done by art flows from the chief craftsman to the under-crafts-men, who work with their hands. Since then the eternal law is the plan of government in the Chief Governor, all the plans of government in the inferior governors must be derived from the eternal law. But these plans of inferior governors are all other laws besides the eternal law. Therefore all laws, in so far as they partake of right reason, are derived from the eternal law. Hence Augustine says (De Lib. Arb. i, 6) that “in temporal law there is nothing just and lawful, but what man has drawn from the eternal law.”

(…)

Question 94. The natural law

- What is the natural law?

- What are the precepts of the natural law?

- Are all acts of virtue prescribed by the natural law?

- Is the natural law the same in all?

- Is it changeable?

- Can it be abolished from the heart of man?

Article 1. Whether the natural law is a habit?

(…)

I answer that, A thing may be called a habit in two ways. First, properly and essentially: and thus the natural law is not a habit. For it has been stated above (I-II:90:1 ad 2) that the natural law is something appointed by reason, just as a proposition is a work of reason. Now that which a man does is not the same as that whereby he does it: for he makes a becoming speech by the habit of grammar. Since then a habit is that by which we act, a law cannot be a habit properly and essentially.

Secondly, the term habit may be applied to that which we hold by a habit: thus faith may mean that which we hold by faith. And accordingly, since the precepts of the natural law are sometimes considered by reason actually, while sometimes they are in the reason only habitually, in this way the natural law may be called a habit. Thus, in speculative matters, the indemonstrable principles are not the habit itself whereby we hold those principles, but are the principles the habit of which we possess.

(…)

Question 95. Human law

- Its utility

- Its origin

- Its quality

- Its division

(…)

Article 2. Whether every human law is derived from the natural law?

(…)

I answer that, As Augustine says (De Lib. Arb. i, 5) “that which is not just seems to be no law at all”: wherefore the force of a law depends on the extent of its justice. Now in human affairs a thing is said to be just, from being right, according to the rule of reason. But the first rule of reason is the law of nature, as is clear from what has been stated above (I-II:91:2 ad 2). Consequently every human law has just so much of the nature of law, as it is derived from the law of nature. But if in any point it deflects from the law of nature, it is no longer a law but a perversion of law.

But it must be noted that something may be derived from the natural law in two ways: first, as a conclusion from premises, secondly, by way of determination of certain generalities. The first way is like to that by which, in sciences, demonstrated conclusions are drawn from the principles: while the second mode is likened to that whereby, in the arts, general forms are particularized as to details: thus the craftsman needs to determine the general form of a house to some particular shape. Some things are therefore derived from the general principles of the natural law, by way of conclusions; e.g. that “one must not kill” may be derived as a conclusion from the principle that “one should do harm to no man”: while some are derived therefrom by way of determination; e.g. the law of nature has it that the evil-doer should be punished; but that he be punished in this or that way, is a determination of the law of nature.

Accordingly both modes of derivation are found in the human law. But those things which are derived in the first way, are contained in human law not as emanating therefrom exclusively, but have some force from the natural law also. But those things which are derived in the second way, have no other force than that of human law.

(…)

Question 96. The power of human law

- Should human law be framed for the community?

- Should human law repress all vices?

- Is human law competent to direct all acts of virtue?

- Does it bind man in conscience?

- Are all men subject to human law?

- May those who are under the law act beside the letter of the law?

Article 1. Whether human law should be framed for the community rather than for the individual?

(…)

I answer that, Whatever is for an end should be proportionate to that end. Now the end of law is the common good; because, as Isidore says (Etym. v, 21) that “law should be framed, not for any private benefit, but for the common good of all the citizens.” Hence human laws should be proportionate to the common good. Now the common good comprises many things. Wherefore law should take account of many things, as to persons, as to matters, and as to times. Because the community of the state is composed of many persons; and its good is procured by many actions; nor is it established to endure for only a short time, but to last for all time by the citizens succeeding one another, as Augustine says (De Civ. Dei ii, 21; xxii, 6).

(…)

Article 4. Whether human law binds a man in conscience?

(…)

I answer that, Laws framed by man are either just or unjust. If they be just, they have the power of binding in conscience, from the eternal law whence they are derived, according to Proverbs 8:15: “By Me kings reign, and lawgivers decree just things.” Now laws are said to be just, both from the end, when, to wit, they are ordained to the common good—and from their author, that is to say, when the law that is made does not exceed the power of the lawgiver—and from their form, when, to wit, burdens are laid on the subjects, according to an equality of proportion and with a view to the common good. For, since one man is a part of the community, each man in all that he is and has, belongs to the community; just as a part, in all that it is, belongs to the whole; wherefore nature inflicts a loss on the part, in order to save the whole: so that on this account, such laws as these, which impose proportionate burdens, are just and binding in conscience, and are legal laws.

On the other hand laws may be unjust in two ways: first, by being contrary to human good, through being opposed to the things mentioned above—either in respect of the end, as when an authority imposes on his subjects burdensome laws, conducive, not to the common good, but rather to his own cupidity or vainglory—or in respect of the author, as when a man makes a law that goes beyond the power committed to him—or in respect of the form, as when burdens are imposed unequally on the community, although with a view to the common good. The like are acts of violence rather than laws; because, as Augustine says (De Lib. Arb. i, 5), “a law that is not just, seems to be no law at all.” Wherefore such laws do not bind in conscience, except perhaps in order to avoid scandal or disturbance, for which cause a man should even yield his right, according to Matthew 5:40-41: “If a man . . . take away thy coat, let go thy cloak also unto him; and whosoever will force thee one mile, go with him other two.”

Secondly, laws may be unjust through being opposed to the Divine good: such are the laws of tyrants inducing to idolatry, or to anything else contrary to the Divine law: and laws of this kind must nowise be observed, because, as stated in Acts 5:29, “we ought to obey God rather than man.”

(…)

Thomas Aquinas. DE REGNO. ON KINGSHIP. TO THE KING OF CYPRUS. https://laisve.lt/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/Aquitane-De-Regno.pdf

BOOK ONE

CHAPTER 1. WHAT IS MEANT BY THE WORD ‘KING’

[2] The first step in our undertaking must be to set forth what is to be understood by the term king.

[3] In all things which are ordered towards an end, wherein this or that course may be adopted, some directive principle is needed through which the due end may be reached by the most direct route. A ship, for example, which moves in different directions. according to the impulse of the changing winds, would never reach its destination were it not brought to port by the skill of the pilot. Now, man has an end to which his whole life and all his actions are ordered; for man is an intelligent agent, and it is clearly the part of an intelligent agent to act in view of an end. Men also adopt different methods in proceeding towards their proposed end, as the diversity of men’s pursuits and actions clearly indicates. Consequently man needs some directive principle to guide him towards his end.

(…)

CHAPTER 3. WHETHER IT IS MORE EXPEDIENT FOR A CITY OR PROVINCE TO BE RULED BY

ONE MAN OR BY MANY

[16] Having set forth these preliminary points we must now inquire what is better for a

province or a city: whether to be ruled by one man or by many.

[17] This question may be considered first from the viewpoint of the purpose of government. The aim of any ruler should be directed towards securing the welfare of that which he undertakes to rule. The duty of the pilot, for instance, is to preserve his ship amidst the perils of the sea. and to bring it unharmed to the port of safety. Now the welfare and safety of a multitude formed into a society lies in the preservation of its unity, which is called peace. If this is removed, the benefit of social life is lost and, moreover, the multitude in its disagreement becomes a burden to itself. The chief concern of the ruler of a multitude, therefore, is to procure the unity of peace. It is not even legitimate for him to deliberate whether he shall establish peace in the multitude subject to him, just as a physician does not deliberate whether he shall heal the sick man encharged to him, for no one should deliberate about an end which he is obliged to seek, but only about the means to attain that end. Wherefore the Apostle, having commended the unity of the faithful people, says: “Be ye careful to keep the unity of the spirit in the bond of peace.” Thus, the more efficacious a. government is in keeping the unity of peace, the more useful it will be. For we call that more useful which leads more directly to the end. Now it is manifest that what is itself one can more efficaciously bring about unity than several—just as the most efficacious cause of heat is that which is by its nature hot. Therefore the rule of one man is more useful than the rule of many.

(…)

CHAPTER 4. THAT THE DOMINION OF A TYRANT IS THE WORST

[21] Just as the government of a king is the best, so the government of a tyrant is the worst.

[22] For democracy stands in contrary opposition to polity, since both are governments carried on by many persons, as is clear from what has already been said; while oligarchy is the opposite of aristocracy, since both are governments carried on by a few persons; and kingship is the opposite of tyranny since both are carried on by one person. Now, as has been shown above, monarchy is the best government. If, therefore, “it is the contrary of the best that is worst.” it follows that tyranny is the worst kind of government.

(…)

CHAPTER 6. THAT IT IS A LESSER EVIL WHEN A MONARCHY TURNS INTO TYRANNY THAN

WHEN AN ARISTOCRACY BECOMES CORRUPT

[36] When a choice is to be made between two things, from both of which danger impends, surely that one should be chosen from which the lesser evil follows. Now, lesser evil follows from the corruption of a monarchy (which is tyranny) than from the corruption of an aristocracy.

[37] Group government [polyarchy] most frequently breeds dissension. This dissension runs counter to the good of peace which is the principal social good. A tyrant, on the other hand, does not destroy this good, rather he obstructs one or the other individual interest of his subjects—unless, of course, there be an excess of tyranny and the tyrant rages against the whole community. Monarchy is therefore to be preferred to polyarchy, although either form of government might become dangerous.

[38] Further, that from which great dangers may follow more frequently is, it would seem, the more to be avoided. Now, considerable dangers to the multitude follow more frequently from polyarchy than from monarchy. There is a greater chance that, where there are many rulers, one of them will abandon the intention of the common good than that it will be abandoned when there is but one ruler. When any one among several rulers turns aside from the pursuit of the common good, danger of internal strife threatens the group because, when the chiefs quarrel, dissension will follow in the people. When, on the other hand, one man is in command, he more often keeps to governing for the sake of the common good. Should he not do so, it does not immediately follow that he also proceeds to the total oppression of his subjects. This, of course, would be the excess of tyranny and the worst wickedness in government, as has been shown above. The dangers, then, arising from a polyarchy are more to be guarded against than those arising from a monarchy.

[39] Moreover, in point of fact, a polyarchy deviates into tyranny not less but perhaps more frequently than a monarchy. When, on account of there being many rulers, dissensions arise in such a government, it often happens that the power of one preponderates and he then usurps the government of the multitude for himself. This indeed may be clearly seen from history. There has hardly ever been a polyarchy that did not end in tyranny. The best illustration of this fact is the history of the Roman Republic. It was for a long time administered by the magistrates but then animosities, dissensions and civil wars arose and it fell into the power of the most cruel tyrants. In general, if one carefully considers what has happened in the past and what is happening in the present, he will discover that more men have held tyrannical sway in lands previously ruled by many rulers than in those ruled by one.

[40] The strongest objection why monarchy, although it is “the best form of government”, is not agreeable to the people is that, in fact, it may deviate into tyranny. Yet tyranny is wont to occur not less but more frequently on the basis of a polyarchy than on the basis of a monarchy. It follows that it is, in any case, more expedient to live under one king than under the rule of several men.

Questions for Reflection

1. If a tradition was the fruit of human reason (at some historical moment), is it sensible to discard a tradition without first analyzing whether the historical reason that originated the tradition was incorrect or no longer correct?

2. In many countries, positive law precedes customs and traditions as a source of law. What are the risks arising from a legal system structured in this way? What are the risks of a reversal of precedence? What is gained by a reversal of precedence?

3. What are the norms that make up God-given law?

4. The rule of one person is defended by Thomas Aquinas because it best preserves the unity of the city. To what extent does this argument hold up in a country like the United States or Brazil? Are there other arguments that can justify this preference?

5. How might Aquinas’s justification for resisting tyranny—when rulers act against divine or natural law—parallel contemporary protest movements against corrupt or oppressive governments in regions like the Middle East or Latin America?

6. Reflect on the role of reason in participating in natural law according to Aquinas; what implications does this have for educating citizens in democratic societies to discern just laws from unjust ones?

7. How does Aquinas’s concept of eternal law as the divine plan governing all creation influence contemporary debates on whether moral absolutes should underpin international human rights treaties?

Leave a comment