Introduction: Historical Context and Biography

Aurelius Augustine, known as Saint Augustine, born in 354 in Tagaste (present-day Algeria) and died in 430, was one of the most influential Christian thinkers, converting to Christianity in 386 and becoming Bishop of Hippo (present-day Annaba, Algeria) in 396. His period was marked by the decline of the Roman Empire, especially after the sack of Rome by the Visigoths in 410, an event that strongly influenced his work, The City of God, completed between 413 and 426.

Figure 8. Saint Augustine of Hippo receiving the Most Sacred Heart of Jesus.

Author: Philippe de Champaigne (1602-1674), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Saint_Augustine_by_Philippe_de_Champaigne.jpg

Augustine’s ideas reflect the transition from the ancient to the medieval world, with a significant impact on theology and political philosophy.

On Free Choice of the Will

‘On Free Choice of the Will‘ is Augustine’s central work, reflecting his view of human nature. The work’s theme is the problem of human freedom and the origin of moral evil (sin).

Augustine argues that God created man with the ability to choose between good and evil. Thus, committing evil is nothing more than submitting one’s will to passions, seeking personal satisfaction in earthly things rather than the eternal goods that come from faith.

The City of Man and the City of God

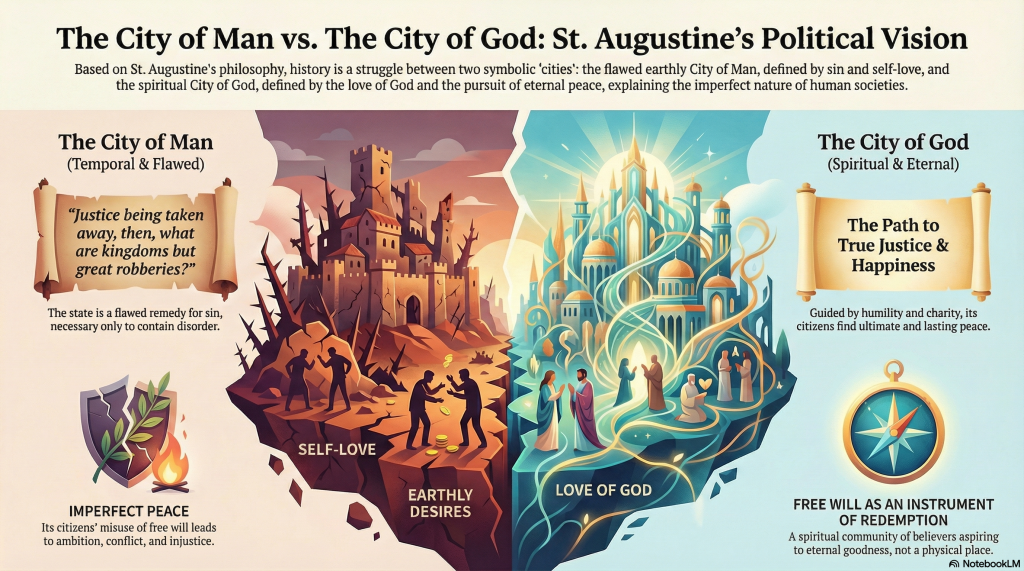

Also at the heart of Augustine’s political thought is the distinction between the city of man and the city of God, detailed in “The City of God.“

The city of man is described as “temporal and flawed,” reflecting the idea that human societies are imperfect due to the misuse of free will. This city is characterized by self-love, leading to ambition, conflict, and injustice.

In the city of man, governments and institutions are products of this fallibility, where free will often leads to ambition, conflict, and injustice. The state, necessary to contain evil, is seen as a remedy for sin, but also flawed, as rulers, using their free will, can abuse their power, resulting in tyranny or unjust wars.

In contrast, the city of God is founded on love for God and the aspiration for eternal good. It is not a physical entity, but a spiritual community of believers, guided by justice, charity, and humility, where true happiness is found.

Augustine details the story as a narrative of the conflict between these two cities. Throughout history, the citizens of both cities coexist, creating tensions. In the city of men, free will perpetuates disorder; in the city of God, it is an instrument of redemption. This interaction reflects the fragility of human institutions, always vulnerable to moral failure.

At the end of time, in the city of God, free will is redeemed, allowing the faithful to choose love for God and align themselves with divine will, achieving true peace and justice.

| Ronald Reagan on Religious Liberty Ronald Wilson Reagan (1911 – 2004) was an American politician who served as the 40th president of the United States from 1981 to 1989. At a Conference on Religious Liberty held in April 16, 1985, he said: “The history of religion and its impact on civilization cannot be summarized in a few days or — never mind minutes. But one of the great shared characteristics of all religions is the distinction they draw between the temporal world and the spiritual world. All religions, in effect, echo the words of the Gospel of St. Matthew: “Render, therefore, unto Caesar the things which are Caesar’s; and unto God the things that are God’s.” What this injunction teaches us is that the individual cannot be entirely subordinate to the state, that there exists a whole other realm, an almost mysterious realm of individual thought and action which is sacred and which is totally beyond and outside of state control. This idea has been central to the development of human rights. Only in an intellectual climate which distinguishes between the city of God and the city of man and which explicitly affirms the independence of God’s realm and forbids any infringement by the state on its prerogatives, only in such a climate could the idea of individual human rights take root, grow, and eventually flourish. We see this climate in all democracies and in our own political tradition. The founders of our republic rooted their democratic commitment in the belief that all men are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights. And so, they created a system of government whose avowed purpose was and is the protection of those God-given rights. But as all of you know only too well, there are many political regimes today that completely reject the notion that a man or a woman can have a greater loyalty to God than to the state. Marx’s central insight when he was creating his political system was that religious belief would subvert his intentions. Under the Communist system, the ruling party would claim for itself the attributes which religious faith ascribes to God alone, and the state would be final arbiter of youth — or truth, I should say, justice and morality. I guess saying youth there instead of truth was just a sort of a Freudian slip on my part. [Laughter] Marx declared religion an enemy of the people, a drug, an opiate of the masses. And Lenin said: “Religion and communism are incompatible in theory as well as in practice . . . We must fight religion.” All of this illustrates a truth that, I believe, must be understood. Atheism is not an incidental element of communism, not just part of the package; it is the package. In countries which have fallen under Communist rule, it is often the church which forms the most powerful barrier against a completely totalitarian system. And so, totalitarian regimes always seek either to destroy the church or, when that is impossible, to subvert it.“ (The full speech can be read at: https://www.reaganlibrary.gov/archives/speech/remarks-conference-religious-liberty) |

The Nature of Power and the State

Augustine sees the state as a remedy for sin, necessary to contain disorder, but not as an end in itself. In “The City of God,” he defines the state as an association of people united by a consensus on the common good, evaluating their morality by the ultimate goal. The city of men seeks peace, understood as natural order and subordination, from emotional control to state hierarchy, but this peace is always precarious and incomplete.

The concept of free will influences Augustine’s view of power and authority. He argues that rulers must use their free will to promote the common good, but they must recognize that their authority derives from God and govern with justice and humility. Human law, for Augustine, must be guided by divine law, for only then can free will be channeled toward good. This reflects his belief in the supremacy of the city of God over the city of men, where free will, without grace, often leads to abuses such as religious coercion or unjust wars.

Regarding slavery, Augustine sees it as an evil useful for maintaining order, but not morally justified.

War and Peace: Just War Theory

Augustine develops the theory of just war (bellum iustum), arguing that war can be legitimate if declared by a competent authority, with a just cause, and the intention of promoting peace. However, he recognizes that war is a result of sin and is a necessary evil in a fallen world. Perfect peace exists only in the city of God, while temporal peace is always fragile and morally neutral, pursued by both cities.

Augustine’s just war theory is also connected to free will. For him, free will is both the cause of the necessity of war and the basis for the possibility of a just war, reflecting the ambiguity of the human condition in the city of men.

Church and State: Distinction and Influence

Augustine advocates a distinction between Church and State, with the Church providing moral guidance and the State maintaining civil order. However, he believes that the State should support Christianity, reflecting the supremacy of divine law. This view influenced the medieval idea of the “two swords,” with the Church having spiritual authority and the State temporal, but subordinate to the Church’s moral principles. He also justifies religious coercion, defending the use of force to compel heretics (such as the Donatists) to return to the Church, arguing that this is an act of paternalistic love, comparable to a father disciplining children or restraining a madman.

Connection to the Circular Diagram of Political Mentalities

Augustine’s thought is one of the foundations of Traditionalist Conservative thought, one of the branches of Authoritarian Conservatives, characterized by its support for legitimate authority and the need for order to curb sin, with a strong emphasis on moral and religious foundations. His view of the city of man as flawed resonates with conservative perspectives that emphasize human imperfection and the need for moral structures.

Influence on Later Political Thought

Augustine profoundly influenced medieval political theory, especially the idea of the “two swords,” which justified the distinction between spiritual and temporal power, but also the supremacy of the Church in moral matters. His legacy includes a pessimistic view of human capacity to create perfect societies, emphasizing the need for humility and vigilance, and remains relevant in contemporary discussions about the role of religion in politics and the limitations of state power.

Summary Table: Central Aspects of Augustine’s Political Thought

| Aspect | Description |

| City of Men: | Temporal, flawed, marked by sin, self-love, and conflict. |

| City of God: | Spiritual, eternal, based on the love of God, true justice, and happiness. |

| State: | Necessary for order, but limited, incapable of salvation, subordinate to the Church. |

| Just War: | Legitimate if by competent authority, just cause, and intention of peace, resulting from sin. |

| Church and State: | Clear distinction, with the Church providing moral guidance and the State supporting religion. |

| Influence: | Founded the medieval theory of the “two swords,” impacted Saint Thomas Aquinas and beyond. |

| Conversion: | Justifies religious coercion, defending the use of force to compel heretics. |

Conclusion

Saint Augustine offers profound insight into the fallibility of the human city and the hope of the city of God, highlighting the limitations of human institutions and the need for a divine moral foundation. His philosophy, rooted in the Christian context, provides enduring insights into justice, authority, and the role of religion, and is one of the foundational authors for Traditionalist Conservatives (one type of authoritarian conservative) in the circle diagram.

Selected Texts

Augustine. On the Free Choice of the Will, On Grace and Free Choice, and Other Writings edited and translated by Peter King. University of Toronto

On the Free Choice of the Will

Book 1

augustine: (…) First of all, tell me whether promulgating a written law is helpful to human beings living this present life.

evodius: Obviously. States and societies are made up out of these human beings.

augustine: Well, these human beings and societies are the same sort of things. Are they eternal and completely unable to change or perish? Or are they instead changeable and subject to time?

evodius: Changeable, plainly, and subject to time; who could doubt it?

augustine: Suppose that a society were well ordered, responsible, and a watchful guardian of the common welfare, one in which each person regards his private interest as less valuable than the public interest. Then is it not right to enact a law whereby this society is allowed to create its own governing officials, through whom the public interest is overseen?

evodius: Quite right.

augustine: Well, now suppose that the same society gradually becomes corrupted. Private interest is put before public interest; votes are bought and sold; degraded by those who covet honors, society hands its rulership over to disgraceful criminals. Would it not again be right if a good person were then found, someone more capable than the rest, who would take the power to confer honors away from society and restrict its choice to a few good people, or even to just one good person?

evodius: Rightly so.

augustine: Then, although these two laws7 seem to be contrary to one another – one of them vests the power of conferring honors in the society, whereas the other takes it away – and although the latter was enacted so that the two laws cannot both hold simultaneously in one state, are we to say that one of them is unjust and hardly ought to have been enacted?

evodius: Not at all.

augustine: Then let us call a law temporal if, although it is just, it can justly be changed in the course of time. Do you agree?

evodius: Fine.

augustine : Well, consider the law referred to as “supreme reason.”8 It should always be obeyed; through it good people deserve a happy life and evil people an unhappy one; and finally through it temporal law is both rightly enacted and rightly changed. Any intelligent person can see that it is unchangeable and eternal. Can it ever be unjust that evil people are unhappy while good people are happy? Can it ever be unjust that an orderly and responsible society sets up governing officials for itself while a dissolute and worthless society lacks this privilege?

evodius: I see that this law is eternal and unchangeable.

augustine: I think you also see, along with this, that nothing in the temporal law is just and legitimate which human beings have not derived from the eternal law. If a given society justly conferred honors at one time but not at another, this shift in the temporal law, to be just, must derive from the eternal law whereby it is always just for a responsible society to confer honors and not for an irresponsible one. Is your view different?

evodius: No, I agree.

augustine: So to explain concisely as far as I can the notion of eternal law that is stamped on us: I t is the law according to which it is just for all things to be completely in order. If you think otherwise, say so.

evodius: I have no objection. What you say is true.

augustine : This law, on the basis of which all temporal laws made to govern human beings are altered [at different times], is one. Therefore it cannot itself be altered in any way, can it?

evodius: I understand that this cannot happen at all. No force, no chance, no disaster could ever make it not just for things to be completely in order.

(…)

Book 2

evodius: Now if possible, explain to me why God gave human beings free choice of the will. If we had not received it, we surely would not be able to sin.

augustine: Do you already know for sure that God gave us something which you think we should not have been given?

evodiust: As far as I seemed to understand matters in Book 1, we have free choice of the will, and we sin through it alone.

augustine: I too remember that this was made evident to us then. But I have just asked you whether you know that God clearly gave us what we have and through which we sin.

evodius: No one else, I think. We have our existence from God; whether we sin or act rightly, we deserve penalty or reward from Him.

augustine: I would also like to know whether you know this unequivocally, or you are induced by authority to believe it readily, even though you do not know it.

evodius: I grant that at first I believed this on authority. But what is more true than that every good is from God, that everything just is good, that a penalty for sinners and a reward for those acting rightly is just? From this it follows that it is God who bestows unhappiness on sinners and happiness on those acting rightly.

augustine: I do not disagree, but I am asking about the other point, namely: How do you know that we have our existence from God? You did not explain this now. Instead, you explained that we deserve penalty or reward from God.

evodius: The answer to this question also seems to be clear, precisely on the grounds that God redresses sins – at least, if all justice comes from Him; for while conferring benefits on strangers is a sign of someone’s goodness, redressing [the wrongdoings] of strangers is not thereby a sign of someone’s justice. Accordingly, it is clear that we belong to God, since

He is not only most generous to us in His excellence, but also is most just in redressing [wrongdoing]. In addition, I proposed and you granted that everything good is from God; human beings can also be understood to be from God on this score. For a human being qua human being is something good, since he can live rightly when he wills to.

augustine: Obviously, if these things are so, the question you raised has been solved, [as follows].

[1] If a person is something good and could act rightly only because he willed to, then he ought to have free will, without which he could not act rightly. We should not believe that, because a person also sins through it, God gave it to him for this purpose. The fact that a person cannot live rightly without it is therefore a sufficient reason why it should have been given to him.

[2] Free will can also be understood to be given for this reason: If anyone uses it in order to sin, the divinity redresses him [for it]. This would happen unjustly if free will had been given not only for living rightly but also for sinning. How would God justly redress someone who made use of his will for the purpose for which it was given? Now, however, when God punishes the sinner, what does He seem to be saying but: “Why did you not make use of free will for the purpose for which I gave it to you?” – that is, for acting rightly.

[3] If human beings lacked free choice of the will, how could there be the good in accordance with which justice itself is praised in condemning sins and honoring right deeds? For what does not come about through the will would neither be sinning nor acting rightly. Consequently, penalty and reward would be unjust if human beings did not have free will. There ought to be justice in punishment and in reward, since justice is one of the goods that are from God.

Hence God ought to have given free will to human beings.

(…)

THE WORKS OF AURELIUS AUGUSTINE, BISHOP OF HIPPO. A NEW TRANSLATION. Edited by the REV. MARCUS DODS, M.A.

4. How like kingdoms without justice are to robberies.

Justice being taken away, then, what are kingdoms but great robberies? For what are robberies themselves, but little kingdoms? The band itself is made up of men; it is ruled by the authority of a prince, it is knit together by the pact of the confederacy; the booty is divided by the law agreed on. If, by the admittance of abandoned men, this evil increases[Pg 140] to such a degree that it holds places, fixes abodes, takes possession of cities, and subdues peoples, it assumes the more plainly the name of a kingdom, because the reality is now manifestly conferred on it, not by the removal of covetousness, but by the addition of impunity. Indeed, that was an apt and true reply which was given to Alexander the Great by a pirate who had been seized. For when that king had asked the man what he meant by keeping hostile possession of the sea, he answered with bold pride, “What thou meanest by seizing the whole earth; but because I do it with a petty ship, I am called a robber, whilst thou who dost it with a great fleet art styled emperor.”

Augustine. Letter 93 (A.D. 408).To Vincentius.

Chapter 9

28. We, however, are certain that no one could ever have been warranted in separating himself from the communion of all nations, because every one of us looks for the marks of the Church not in his own righteousness, but in the Divine Scriptures, and beholds it actually in existence, according to the promises. For it is of the Church that it is said,As the lily among thorns, so is my

love among the daughters; Song of Songs 2:2 which could be called on the one hand thorns

only by reason of the wickedness of their manners, and on the other hand daughters

by reason of their participation in the same sacraments. Again, it is the Church which says, From the end of the earth have I cried unto You when my heart was overwhelmed;

and in another Psalm, Horror has kept me back from the

wicked that forsake Your law; and, I beheld the transgressors, and was grieved.

It is the same which says to her Spouse: Tell me where You feed, where You rest at noon: for why should I be as one veiled beside the flocks of Your companions?

Song of Songs 1:7 This is the same as is said in another place: Make

known to me Your right hand, and those who are in heart taught in wisdom; in whom, as they shine with light and glow with love, You rest as in noontide; lest perchance, like one veiled, that is, hidden and unknown, I should run, not to Your flock, but to the flocks of Your companions, i.e. of heretics, whom the bride here calls companions, just as He called the thorns Song of Songs 2:2 daughters,

because of common participation in the sacraments: of which persons it is elsewhere said: You were a

man, mine equal, my guide, my acquaintance, who took sweet food together with me; we walked unto the house of God in company. Let death seize upon them, and let them go down quick into hell, like Dathan and Abiram, the authors of an impious schism.

Questions for Reflection

1. Is there virtue without free will? Or can a person who merely obeys the law under penalty of punishment (or for another reason that renders them incapable of evil) be considered virtuous?

2. According to Augustine, the law should not attempt to force people to do what is right or avoid what is wrong, but rather guide them to be just. How can we create such a legal system? How can we reconcile such a prescription with Augustine’s understanding of the legitimacy of religious coercion (the use of force to compel heretics)?

3. Imagine a hypothetical Islamic invasion taking over some European countries. Would you advocate a just war against Islam? What about coercion as a mechanism for conversion? What is the limit of acceptable coercion?

4. What kind of people does a totalitarian state produce, regulating every aspect of human life with total surveillance (like the USSR, where children were indoctrinated to watch and report on their parents, or like the Chinese social credit system, which seeks to monitor every action of Chinese citizens by every available means and score their behavior for employment, credit, and other purposes)?

5. What legitimizes a government’s taxation (taxation is theft, some libertarians would say) and distinguishes it from a gang of thieves?

6. Is it possible for a government to be non-flawed and imperfect?

7. Consider that the church is composed of human beings, and therefore fallible. Still, are the Church’s moral guidelines for rulers a good check on state actions?

8. Consider the persecution of Jews in Nazi Germany. Consider also Hannah Arendt’s concept of the banality of evil in “Eichmann in Jerusalem” (evil is not necessarily motivated by people with demonic motivations or deep passions, but rather by people incapable of making moral judgments, acting bureaucratically, with excessive obedience and a lack of reflection). Was Augustine right when he saw evil as the absence of good (of God)? Can we consider as good men those who simply do not interfere (not my problem, some say) when they see evil occurring? What is the expected attitude of good men?

9. According to Augustine:

“(…) And generally in respect of all that we seek or shun, as a man’s will is attracted or repelled, so it is changed and turned into these different affections. Wherefore the man who lives according to God, and not according to man, ought to be a lover of good, and therefore a hater of evil. And since no one is evil by nature, but whoever is evil is evil by vice, he who lives according to God ought to cherish towards evil men a perfect hatred, so that he shall neither hate the man because of his vice, nor love the vice because of the man, but hate the vice and love the man. For the vice being cursed, all that ought to be loved, and nothing that ought to be hated, will remain.”

What exactly does it mean to love a man who has committed a heinous crime and hate only the crime? Does such a philosophy contradict or apply to criminal law? How?

Leave a comment