Introduction

Niccolò de Bernardo dei Machiavelli, born in 1469 and died in 1527, is a central figure in the transition from ancient and medieval thought to modern politics.

He lived in Renaissance Florence, a period of political instability, rivalries between city-states, foreign invasions, and the decline of medieval theocentric politics.

He served as a diplomat and secretary in the Florentine Republic. He witnessed the rise and fall of leaders such as Cesare Borgia and the Medici family.

He was exiled after the Medici’s return, during which time he wrote The Prince (1513) and Discourses on Livy.

Figure 10. Niccolò Machiavelli

Author: Lorenzo Bartollini (1777-1850)

Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Niccolo_Machiavelli_uffizi.jpg

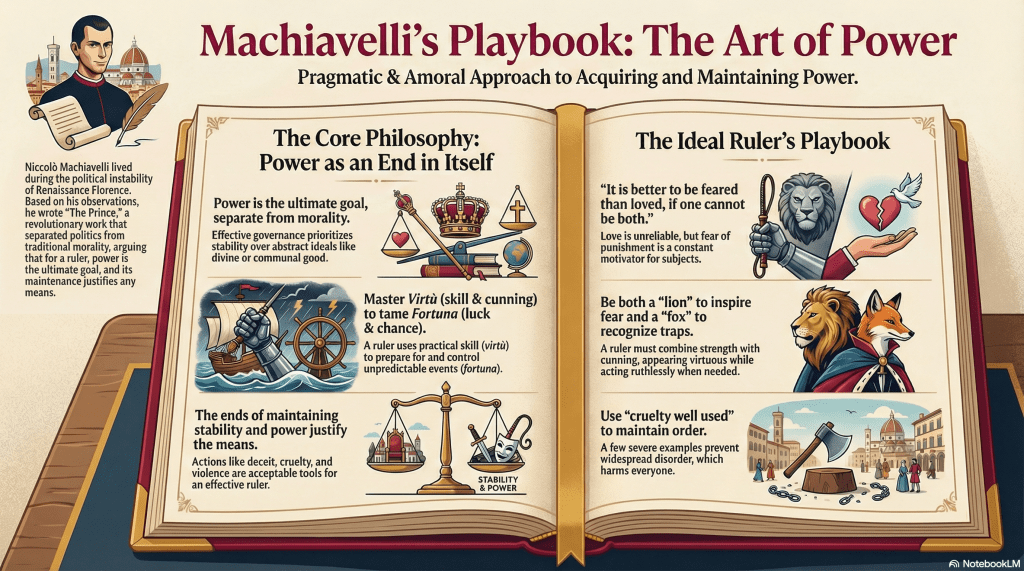

With his view of power as an end in itself, distinct from moral or divine considerations, he shaped the way of seeing power for some ideological currents, distancing it from the search for the common good, typical of traditional moral structures (for example, the divine law of Thomas Aquinas), arguing that the acquisition and maintenance of power justify the means.

Central Political Ideas: Power as the Ultimate Goal

The Prince:

Machiavelli’s central thesis is that effective governance prioritizes virtù (skill, cunning, adaptability) and fortuna (luck, chance) over moral virtue. Power is an end in itself, not a means to the divine or communal good (in contrast to Thomas Aquinas or Augustine).

His famous maxim is: “It is better to be feared than loved, if one cannot be both” (The Prince, Chapter XVII).

Virtue and Fortune

Machiavelli introduces concepts that challenge traditional political ethics:

Virtù: A ruler’s ability to shape events through cunning, courage, and adaptability. It is not a moral virtue, but a practical skill. Cesare Borgia, with his ability to unify Romagna through ruthless tactics, is the paradigmatic example of virtù.

Fortuna: Luck or chance, compared to a torrential river that can devastate or be controlled by dikes. A wise ruler uses virtù to tame fortune, like a leader preparing defenses before a crisis (The Prince, Chapter XXV).

Justification of the Means:

The ends (stability, power) justify morally questionable means (deceit, violence, betrayal), citing Cesare Borgia’s ruthless tactics as a model of effective government.

Rejection of Idealism:

Criticism of utopian or morally oriented governance (e.g., Plato’s philosopher-king or Christian ethics).

Emphasis on human nature as selfish and prone to conflict, requiring strong and pragmatic leadership.

The Role of Lying:

Rulers must appear virtuous, acting ruthlessly when necessary (metaphor of the “fox and the lion,” The Prince, Chapter XVIII).

Public perception (the appearance of virtue) is as crucial as actual power.

| Lying as a Method In a well-known video, Brazilian President Luiz Ignácio Lula da Silva stated: “I’m tired of traveling the world badmouthing Brazil. It was nice for us to travel the world saying, ‘There are 30 million street children in Brazil.’ We didn’t even know, ‘There are I don’t know how many millions of abortions.’ We just kept quoting numbers, you know? If someone asked for the source, we wouldn’t have it, but we kept quoting numbers.” (https://x.com/i/status/1640411264533839879) |

Characteristics of the Ideal Ruler, According to Machiavelli

Machiavelli’s ideal ruler is a pragmatic and adaptable figure who masters virtù to control fortune. Key characteristics include:

- A willingness to use cruelty and mercy strategically (e.g., Chapter 17: It is better to be feared than loved, but avoid hatred).

- Ability to deceive when necessary (e.g., Chapter 18: Appear virtuous, but act differently if necessary).

- Boldness in seizing opportunities (e.g., Chapter 6: Conquerors like Moses or Romulus who shape their own destiny).

- A focus on stability and power, even at a moral cost (e.g., Chapter 8: “Cruelty well used” to prevent disorder).

| Game of Thrones The series Game of Thrones is an extraordinary source of political learning. In one episode, there’s the following dialogue between two of the show’s most interesting characters, Lord Varys and Petyr “Littlefinger” Baelish. Petyr Baelish, a master manipulator, is the very embodiment of Machiavelli’s legacy, always scheming for power. On the other hand, Lord Varys always seeks to defend what he believes is best for the kingdom and the common good, symbolizing altruistic governance. When they meet in the throne room, built with the thousand blades of those defeated by Aegon the Conqueror, the conversation begins. Baelish boasts about how he forced young Sansa Stark to marry the dwarf Tyrion Lanister against her will and how, without scruples, he handed over an informant of Lord Varys to be shot dead by King Joffery Baratheon with arrows. Afterwards, he reveals his understanding of the power play: (…) Petyr “Littlefinger” Baelish: You’re so right. For instance, when I thwarted your plan to give Sansa Stark to the Tyrells, if I’m going to be honest, I did feel an unmistakable sense of enjoyment there. But your confidant, the one who fed you information about my plans, the one you swore to protect… you didn’t bring her any enjoyment, and she didn’t bring me any enjoyment. She was a bad investment on my part. Luckily, I have a friend who wanted to try something new. Something daring. And he was so grateful to me for providing this fresh experience. Lord Varys: I did what I did for the good of the realm. Petyr “Littlefinger” Baelish: The realm. Do you know what the realm is? It’s the thousand blades of Aegon’s enemies, a story we agree to tell each other over and over, until we forget that it’s a lie. Lord Varys: But what do we have left, once we abandon the lie? Chaos? A gaping pit waiting to swallow us all. Petyr “Littlefinger” Baelish: Chaos isn’t a pit. Chaos is a ladder. Many who try to climb it fail and never get to try again. The fall breaks them. And some, are given a chance to climb. They refuse, they cling to the realm or the gods or love. Illusions. Only the ladder is real. The climb is all there is. (…) An additional Machiavellian lesson from Petyr Belish that cannot be overlooked is that those who aspire to power at any cost desire (and often work toward) chaos. For them, chaos is a ladder… (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HDjNcqQs1yM) |

Machiavelli in the Circular Diagram of Political Mentalities

Primary Alignment: Radical Statist

Machiavelli’s focus on centralized power, control, and the suppression of opposition aligns with radical statist tendencies, as seen in later figures such as Mussolini and Hitler.

His amoral pragmatism foreshadows the totalizing state’s prioritization of power over individual liberties.

However, on the one hand, his valorization of order and strong leadership echoes authoritarian conservative regimes, such as Franco’s Spain, which prioritized stability over liberties.

On the other hand, his willingness to use revolutionary means to achieve political ends resonates with radical leftist groups, with vanguard tactics like those of Lenin.

Opposition to Classical Liberals:

His emphasis on stability over individual liberties places him in direct opposition to classical liberals, who value natural rights and limited government.

Fluidity Between Mindsets:

Machiavelli’s ideas influence a range of mentalities, from authoritarian regimes to pragmatic liberal strategies, especially those who have lost their moral references, reflecting the interconnectedness of the diagram.

Key Points

- Machiavelli prioritizes political effectiveness over morality, arguing that power justifies means such as deception and cruelty.

- In the circular diagram, he aligns himself with radical statists, as opposed to classical liberals, but influences diverse mindsets.

Selected Texts and Analyses

Niccolò Machiavelli. The Prince. Translated and Introduced by Tim Parks. UK: Penguin.

17. Cruelty and compassion. Whether it’s better to be feared or loved

Continuing with our list of qualities, I’m sure every leader would wish to be seen as compassionate rather than cruel.

All the same he must be careful not to use his compassion unwisely. Cesare Borgia was thought to be cruel, yet his cruelty restored order to Romagna and united it, making the region peaceful and loyal. When you think about it, he was much more compassionate than the Florentines whose reluctance to be thought cruel led to disaster in Pistoia. A ruler mustn’t worry about being labelled cruel when it’s a question of keeping his subjects loyal and united; using a little exemplary severity, he will prove more compassionate than the leader whose excessive compassion leads to public disorder, muggings and murder. That kind of trouble tends to harm everyone, while the death sentences that a ruler hands out

affect only the individuals involved. But of all rulers, a man new to power simply cannot avoid a reputation for cruelty, since a newly conquered state is a very dangerous place. Virgil puts these words in Queen Dido’s mouth:

“The difficult situation and the newness of my kingdom

Force me to do these things, and guard my borders everywhere.”*

*Res dura, et regni novitas me talia cogunt

Moliri, et late fines custode tueri.

All the same, a leader must think carefully before believing and responding to certain allegations and not get frightened over nothing. He should go about things coolly, cautiously and humanely: if he’s too trusting, he’ll get careless, and if he trusts no one he’ll make himself unbearable.

These reflections prompt the question: is it better to be loved rather than feared, or vice versa? The answer is that one would prefer to be both but, since they don’t go together easily, if you have to choose, it’s much safer to be feared than loved. We can say this of most people: that they are ungrateful and unreliable; they lie, they fake, they’re greedy for cash and they melt away in the face of danger. So long as you’re generous and, as I said before, not in immediate danger, they’re all

on your side: they’d shed their blood for you, they’d give you their belongings, their lives, their children. But when you need them they turn their backs on you. The ruler who has relied entirely on their promises and taken no other precautions is lost. Friendship that comes at a price, and not because people admire your spirit and achievements, may indeed have been paid for, but that doesn’t mean you really possess it and you certainly won’t be able to count on it when you need it. Men are less worried about letting down someone who has made himself loved than someone who makes himself feared. Love binds when someone recognizes he should be grateful to you, but, since men are a sad lot, gratitude is forgotten the moment it’s inconvenient. Fear means fear of punishment, and that’s something people never forget. All the same, while a ruler can’t expect to inspire love when making himself feared, he must avoid arousing hatred.

Actually, being feared is perfectly compatible with not being hated. And a ruler won’t be hated if he keeps his hands off his subjects’ property and their women. If he really has to have someone executed, he should only do it when he has proper justification and manifest cause. Above all, he mustn’t seize other people’s property. A man will sooner forget the death of his father than the loss of his inheritance. Of course there are always reasons for taking people’s property and a ruler who has started to live that way will never be short of pretexts for grabbing more. On the other hand, reasons for executing a man come more rarely and pass more quickly.

But when a ruler is leading his army and commanding large numbers of soldiers, then above all he must have no qualms about getting a reputation for cruelty; otherwise it will be quite impossible to keep the army united and fit for combat.

One of Hannibal’s most admirable achievements was that despite leading a huge and decidedly multiracial army far from home there was never any dissent among the men or rebellion against their leader whether in victory or defeat. The only possible explanation for this was Hannibal’s tremendous cruelty, which, together with his countless positive qualities, meant that his soldiers always looked up to him with respect and terror. The positive qualities without the cruelty wouldn’t have produced the same effect. Historians are just not thinking when they praise him for this achievement and then

condemn him for the cruelty that made it possible.

To show that Hannibal’s other qualities wouldn’t have done the job alone we can take the case of Scipio, whose army mutinied in Spain. Scipio was an extremely rare commander not only in his own times but in the whole of recorded history, but he was too easy-going and as a result gave his troops a freedom that was hardly conducive to military discipline.

Fabius Maximus condemned him for this in the Senate, claiming that he had corrupted the Roman army. When one of his officers sacked the town of Locri, Scipio again showed leniency; he didn’t carry out reprisals on behalf of the townsfolk and failed to punish the officer’s presumption, so much

so that someone defending Scipio in the Senate remarked that he was one of those many men who don’t make mistakes themselves, but find it hard to punish others who do. If Scipio had gone on leading his armies like this, with time his temperament would have undermined his fame and diminished his glory, but since he took his orders from the Senate, not only was the failing covered up but it actually enhanced his reputation.

Going back, then, to the question of being feared or loved, my conclusion is that since people decide for themselves whether to love a ruler or not, while it’s the ruler who decides whether they’re going to fear him, a sensible man will base his power on what he controls, not on what others have freedom to choose. But he must take care, as I said, that people don’t come to hate him.

25. The role of luck in human affairs, and how to defend against it

I realize that many people have believed and still do believe that the world is run by God and by fortune and that however shrewd men may be they can’t do anything about it and have no way of protecting themselves. As a result they may decide that it’s hardly worth making an effort and just leave events to chance. This attitude is more prevalent these days as a result of the huge changes we’ve witnessed and are still witnessing every day, things that no one could have predicted. Sometimes, thinking it over, I have leaned a bit that way myself.

All the same, and so as not to give up on our free will, I reckon it may be true that luck decides the half of what we do, but it leaves the other half, more or less, to us. It’s like one of those raging rivers that sometimes rise and flood the plain, tearing down trees and buildings, dragging soil from one place and dumping it down in another. Everybody runs for safety, no one can resist the rush, there’s no way you can stop it. Still, the fact that a river is like this doesn’t prevent us from preparing for trouble when levels are low, building banks and dykes, so that when the water rises the next time it can be contained in a single channel and the rush of the river in flood is not so uncontrolled and destructive.

Fortune’s the same. It shows its power where no one has taken steps to contain it, flooding into places where it finds neither banks nor dykes that can hold it back. And if you look at Italy, which has been both the scene of revolutionary changes and the agent that set them in motion, you’ll see it’s a land that has neither banks nor dykes to protect it. Had the country been properly protected, like Germany, Spain and France, either the flood wouldn’t have had such drastic effects or it wouldn’t have happened at all.

I think that is all that need be said in general terms about how to deal with the problem of luck. Going into detail, though, we’ve all seen how a ruler may be doing well one day and then lose power the next without any apparent change in his character or qualities. I believe this is mostly due to the attitude I mentioned above: that is, the ruler trusts entirely to luck and collapses when it changes. I’m also convinced that the successful ruler is the one who adapts to changing times; while the leader who fails does so because his approach is out of step with circumstances.

All men want glory and wealth, but they set out to achieve those goals in different ways. Some are cautious, others impulsive; some use violence, others finesse; some are patient, others quite the opposite. And all these different approaches can be successful. It’s also true that two men can both be cautious but with different results: one is successful and the other fails. Or again you see two men being equally successful but with different approaches, one cautious, the other impulsive. This

depends entirely on whether their approach suits the circumstances, which in turn is why, as I said, two men with different approaches may both succeed while, of two with the same approach, one may succeed and the other not.

This explains why people’s fortunes go up and down. If someone is behaving cautiously and patiently and the times and circumstances are such that the approach works, he’ll be successful. But if times and circumstances change, everything goes wrong for him, because he hasn’t changed his approach to match. You won’t find anyone shrewd enough to adapt his character like this, in part because you can’t alter your natural bias and in part because, if a person has always been successful with a particular approach, he won’t easily be persuaded to drop it. So when the time comes for the cautious man to act impulsively, he can’t, and he comes unstuck. If he did change personality in line with times and circumstances, his luck would hold steady.

Pope Julius II always acted impulsively and lived in times and circumstances so well suited to this approach that things always went well for him. Think of his first achievement, taking Bologna while Giovanni Bentivoglio was still alive.

The Venetians were against the idea, the King of Spain likewise, and Julius was still negotiating the matter with the French. All the same, and with his usual ferocity and impetuousness, the pope set out and led the expedition himself. This put the Venetians and Spanish in a quandary and they were unable to react, the Venetians out of fear and the Spanish because they hoped to recover the whole of the Kingdom of Naples. Meanwhile, the King of France was brought on board: he needed Rome as an ally to check the Venetians and decided that once Julius had made his move he couldn’t deny him armed support without too obviously slighting him.

With this impulsive decision, then, Julius achieved more than any other pope with all the good sense in the world would ever have achieved. Had he waited to have everything arranged and negotiated before leaving Rome, as any other pope would have done, the plan would never have worked.

The King of France would have come up with endless excuses and the Venetians and Spanish with endless warnings. I don’t want to go into Julius’s other campaigns, which were all of a kind and all successful. His early death spared him the experience of failure. Because if times had changed and circumstances demanded caution, he would have been finished. The man would never have changed his ways, because they were natural to him.

To conclude then: fortune varies but men go on regardless. When their approach suits the times they’re successful, and when it doesn’t they’re not. My opinion on the matter is this: it’s better to be impulsive than cautious; fortune is female and if you want to stay on top of her you have to slap and thrust. You’ll see she’s more likely to yield that way than to men who go about her coldly. And being a woman she likes her men young, because they’re not so cagey, they’re wilder and more daring when they master her.

Some questions for reflection:

1. What ends does Machiavelli intend? Who defines which ends justify the means?

2. In a complicated or complex environment, with many actors interfering without us being able to know their actions and true intentions, and therefore with low predictability of the results of individual actions (even if it is the ruler), is it reasonable to judge an individual (the ruler) based solely on the results, disregarding the nature of their actions?

3. What kind of person would rather be feared than loved? Will they be a good leader? Is this the kind of leadership we desire? Under what circumstances are we willing to be led by someone with this profile?

4. In what situations can Machiavelli’s amoral approach be justified? Are there ethical boundaries that a ruler should not cross, even in the name of stability?

5. Is Machiavelli’s view of human nature (selfish and fickle) realistic or overly pessimistic? Are ordinary people as he describes, or are rulers like that?

6. In what environment do Machiavelli’s lessons seem most relevant? Compare an unstable and chaotic regime with a regime of democratic stability?

7. Do rulers who are willing to take any action necessary to seize power need Machiavelli’s lessons?

8. Political science courses often begin with Machiavelli, highlighting his importance to the political thought they classify as modern. Considering the importance of classical authors for classical liberals and moderate conservatives, and considering the rootedness of the Machiavellian mentality in radical leftist thought, could this preference reflect the leftism of the authors in this discipline and/or a lack of intellectual honesty?

Leave a comment