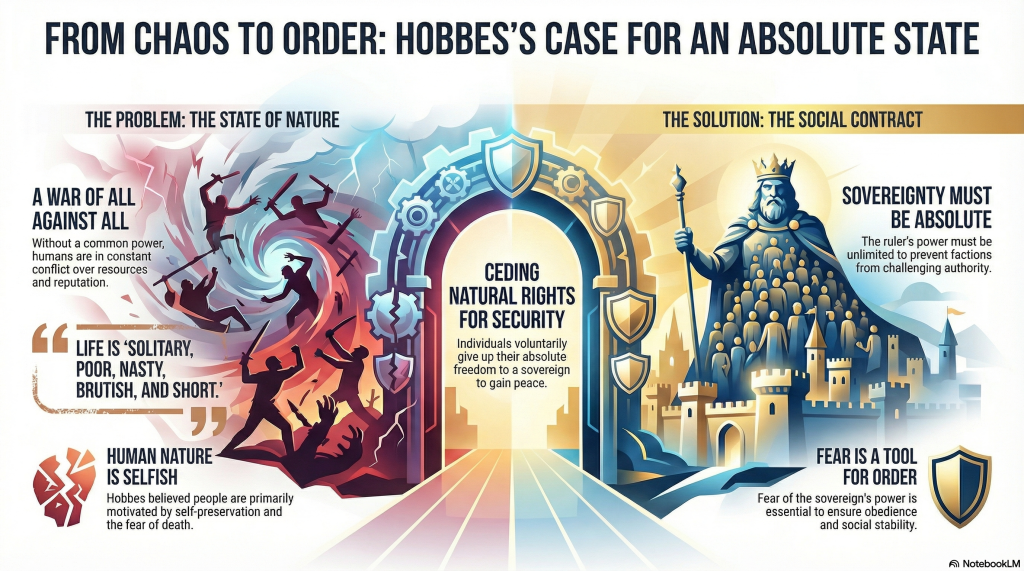

Introduction

Thomas Hobbes, an English political philosopher born in 1588 and died in 1679, is a central figure in modern political thought, especially known for his advocacy of an absolute state as a solution to the disorder and fear inherent in the human condition. His masterpiece, Leviathan (1651), was written during his exile in France, a period marked by the English Civil War (1642-1651), a conflict between King Charles I and Parliament that resulted in the monarch’s execution and the rise of a republic under Oliver Cromwell. This context of profound instability profoundly influenced his philosophy, which sought to respond to the anarchy and violence he observed.

Figure 11: Portrait of Thomas Hobbes.

Author: John Michael Wrigth (1617-1694)

Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Thomas_Hobbes_(portrait).jpg

Historical Context and Influences

Hobbes witnessed the devastating effects of civil war firsthand, seeing it as an example of the “state of nature,” a hypothetical condition where human beings, without a central power, live in constant conflict due to competition for resources and a lack of security. He served as a tutor and secretary to English nobles, but, as a royalist, fled to France to avoid persecution by the parliamentarians. During this exile, he wrote Leviathan, a treatise arguing for the need for an absolute sovereign to maintain social order. His experience was also shaped by scientific influences, such as Francis Bacon’s inductive philosophy and the geometric method, which he applied to politics, seeking to create a “science of politics.”

Central Political Ideas

Hobbes’s ideas revolve around fundamental concepts that challenge previous views, such as those of Aristotle and Thomas Aquinas, which saw the state as a means to the common good or virtue. Instead, Hobbes argued that the state must be absolute, with unlimited power, to prevent chaos. His key concepts include:

State of Nature: A condition of absolute equality and freedom, but also of constant conflict and insecurity, where “the life of man is solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short,” as described in Leviathan, Chapter XIII.

Human Nature: Hobbes saw human beings as motivated primarily by the desire for self-preservation and the fear of death, believing that, unchecked, they are selfish and competitive, leading to the need for a social contract.

Social Contract: An agreement in which individuals cede their natural rights to a sovereign, who then has the power to make and enforce laws to maintain peace, as detailed in Leviathan, Chapter XVII, where he explains that the purpose is to enjoy the benefits of union and mutual protection.

Absolute Sovereignty: The sovereign must have unlimited power to ensure that no faction can challenge his authority, preventing a return to the state of nature.

Fear as a Tool: Hobbes recognized that fear, both of the sovereign and of anarchy, is essential to maintaining obedience and social order, an idea that reflects his pessimistic view of humanity.

| The Social Contract in the COVID-19 Pandemic The COVID-19 pandemic provides a modern example of the Hobbesian mindset in action. During the crisis, many governments implemented strict measures such as lockdowns, mask mandates, mandatory vaccinations, and mobility restrictions, under the guise of protecting public health. Many citizens, frightened by the virus, accepted significant limitations on their individual freedoms and supported the demand that less fearful citizens be forced to submit to such limitations, even at the substantial cost not only to their freedoms but also to their savings and the lives of themselves, their children, and other relatives. In general, instilling fear, whether justified or not, in the population has been a frequent strategy of authoritarian governments to climb the ladder of power. |

Connection to the Diagram of Political Mindsets

Hobbes clearly aligns himself with the “Radical Statists,” who advocate strong, centralized state control. His emphasis on absolute sovereignty and the suppression of dissent places him in direct opposition to the “Classical Liberals,” who value individual liberties and limited government. However, his ideas also influence other authoritarian mindsets, such as the “Authoritarian Conservatives,” who prioritize order and stability, and the “Radical Leftists,” with their desire to impose the social order they aspire to.

Historical Impact and Modern Relevance

Hobbes’s ideas had a profound impact on modern political thought, serving as a justification for authoritarian states with centralized power.

Conclusion

Thomas Hobbes offered a powerful and influential vision of the need for a strong state to prevent anarchy and protect citizens. His theory of the social contract, though controversial, continues to shape political thought and provide insights into the challenges of governing complex societies. In the diagram of political mentalities, he positions himself as a defender of state order, challenging classical liberals and influencing both authoritarian conservatives and radical leftists.

Selected Texts

Thomas Hobbes of Malmesbury. Leviathan or the Matter, Forme, & Power of a Common-wealth Ecclesiasticall and Civill. London, 1651.

(avalilable at: https://www.gutenberg.org/files/3207/3207-h/3207-h.htm)

(…)

So that in the nature of man, we find three principal causes of quarrel. First, competition; secondly, diffidence; thirdly, glory.

The first maketh men invade for gain; the second, for safety; and the third, for reputation. The first use violence, to make themselves masters of other men’s persons, wives, children, and cattle; the second,

to defend them; the third, for trifles, as a word, a smile, a different opinion, and any other sign of undervalue, either direct in their persons or by reflection in their kindred, their friends, their nation, their profession, or their name.

Hereby it is manifest that during the time men live without a common power to keep them all in awe, they are in that condition which is called war; and such a war as is of every man against every man. For

war consisteth not in battle only, or the act of fighting, but in a tract of time, wherein the will to contend by battle is sufficiently known: and therefore the notion of time is to be considered in the nature of war, as it is in the nature of weather. For as the nature of foul weather lieth not in a shower or two of rain, but in an inclination thereto of many days together: so the nature of war consisteth not in actual fighting, but in the known disposition thereto during all the time there is no assurance to the contrary. All other time is peace.

Whatsoever therefore is consequent to a time of war, where every man is enemy to every man, the same consequent to the time wherein men live without other security than what their own strength and their own invention shall furnish them withal. In such condition there is no place for industry, because the fruit thereof is uncertain: and consequently no culture of the earth; no navigation, nor use of the commodities that may be imported by sea; no commodious building; no instruments of moving and removing such things as require much force; no knowledge of the face of the earth; no account of time; no arts; no letters; no society; and which is worst of all, continual fear, and danger of violent death; and the life of man, solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.

(…)

Howsoever, it may be perceived what manner of life there would be, where there were no common power to fear, by the manner of life which men that have formerly lived under a peaceful government use to degenerate into a civil war.

But though there had never been any time wherein particular men were in a condition of war one against another, yet in all times kings and persons of sovereign authority, because of their independency, are in continual jealousies, and in the state and posture of gladiators, having their weapons pointing, and their eyes fixed on one another; that is, their forts, garrisons, and guns upon the frontiers of their kingdoms, and continual spies upon their neighbours, which is a posture of war. But because they uphold thereby the industry of their subjects, there does not follow from it that misery which accompanies the liberty of particular men.

To this war of every man against every man, this also is consequent; that nothing can be unjust. The notions of right and wrong, justice and injustice, have there no place. Where there is no common power, there is no law; where no law, no injustice. Force and fraud are in war the two cardinal virtues. Justice and injustice are none of the faculties neither of the body nor mind. If they were, they might be in a man that were alone in the world, as well as his senses and passions. They are qualities that relate to men in society, not in solitude. It is consequent also to the same condition that there be no propriety, no dominion, no mine and thine distinct; but only that to be every man’s that he can get, and for so long as he can keep it. And thus much for the ill condition which man by mere nature is actually placed in; though with a possibility to come out of it, consisting partly in the passions, partly in his reason.

The passions that incline men to peace are: fear of death; desire of such things as are necessary to commodious living; and a hope by their industry to obtain them. And reason suggesteth convenient articles of peace upon which men may be drawn to agreement. These articles are they which otherwise are called the laws of nature, whereof I shall speak more particularly in the two following chapters.

XIV: Of the First and Second Natural Laws, and Of Contracts

The right of nature, which writers commonly call jus naturale, is the liberty each man hath to use his own power as he will himself for the preservation of his own nature; that is to say, of his own life; and consequently, of doing anything which, in his own judgement and reason, he shall conceive to be the aptest means thereunto.

By liberty is understood, according to the proper signification of the word, the absence of external impediments; which impediments may oft take away part of a man’s power to do what he would, but cannot hinder him from using the power left him according as his judgement and reason shall dictate to him.

A law of nature, lex naturalis, is a precept, or general rule, found out by reason, by which a man is forbidden to do that which is destructive of his life, or taketh away the means of preserving the same, and to omit that by which he thinketh it may be best preserved. For though they that speak of this subject use to confound jus and lex, right and law, yet they ought to be distinguished, because right consisteth in liberty to do, or to forbear; whereas law determineth and bindeth to one of them: so

that law and right differ as much as obligation and liberty, which in one and the same matter are inconsistent.

And because the condition of man (as hath been declared in the precedent chapter) is a condition of war of every one against every one, in which case every one is governed by his own reason, and there is nothing he can make use of that may not be a help unto him in preserving his life against his enemies; it followeth that in such a condition every man has a right to every thing, even to one another’s body. And therefore, as long as this natural right of every man to every thing endureth, there can be no security to any man, how strong or wise soever he be, of living out the time which nature ordinarily alloweth men to live. And consequently it is a precept, or general rule of reason: that every man ought to endeavour peace, as far as he has hope of obtaining it; and when he cannot obtain it, that he may seek and use all helps and advantages of war. The first branch of which rule containeth the first and fundamental law of nature, which is: to seek peace and follow it.

The second, the sum of the right of nature, which is: by all means we can to defend ourselves. From this fundamental law of nature, by which men are commanded to endeavour peace, is derived this second law: that a man be willing, when others are so too, as far forth as for peace and defence of himself he shall think it necessary, to lay down this right to all things; and be contented with so much liberty against other men as he would allow other men against himself. For as long as every man holdeth this right, of doing anything he liketh; so long are all men in the condition of war.

But if other men will not lay down their right, as well as he, then there is no reason for anyone to divest himself of his: for that were to expose himself to prey, which no man is bound to, rather than to dispose himself to peace. This is that law of the gospel: Whatsoever you require that others should do to you, that do ye to them. And that law of all men, quod tibi fieri non vis, alteri ne feceris.

(…)

Reflection Questions

1. To what extent does Hobbes’s view of the state of nature reflect human reality? Is there historical or contemporary evidence that supports or refutes his description?

2. Hobbes argued that sovereignty must be absolute to prevent anarchy. Is this view compatible with modern democratic systems, where power is distributed and there are checks and balances?

3. How do Hobbes’s ideas about human nature influence contemporary public policy?

4. In the diagram of political mindsets, why are Hobbes’s ideas associated with radical statists? How do they relate to other mindsets, such as authoritarian conservatives or classical liberals?

5. How does Hobbes’ depiction of the state of nature as a realm of constant fear and conflict, where life is “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short,” illustrate the potential breakdown of society without a strong central authority, and what parallels can be drawn to contemporary failed states or regions experiencing civil unrest?

6. Discuss the social contract in Hobbes’ philosophy, where individuals surrender natural rights to an absolute sovereign for security; how could this concept critique or support current debates on national security laws that limit civil liberties in democratic nations?

7. Considering the box’s reference to COVID-19 measures as a Hobbesian example of fear-driven compliance, what reflections arise on the ethical implications of governments using public health emergencies to impose lockdowns or mandates in today’s post-pandemic world?

8. How does Hobbes’ justification for an absolute state to remedy disorder and fear contrast with thinkers like Aquinas who prioritized the common good, and how could this tension inform contemporary discussions on balancing individual freedoms with collective security in policies like gun control?

Leave a comment