Introduction

Roger Vernon Scruton (1944 –2020) was a prominent British philosopher, writer, and public intellectual, widely regarded as one of the leading conservative thinkers of the late 20th and early 21st centuries.

Figure 37. Roger Vernon Scruton

Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Roger_Scruton_by_Pete_Helme.jpg

He authored over 50 books and thousands of articles addressing conservatism, theology, aesthetics, and politics on topics ranging from aesthetics and politics to religion and environmentalism, and was knighted in 2016 for his services to philosophy, teaching, and public education.

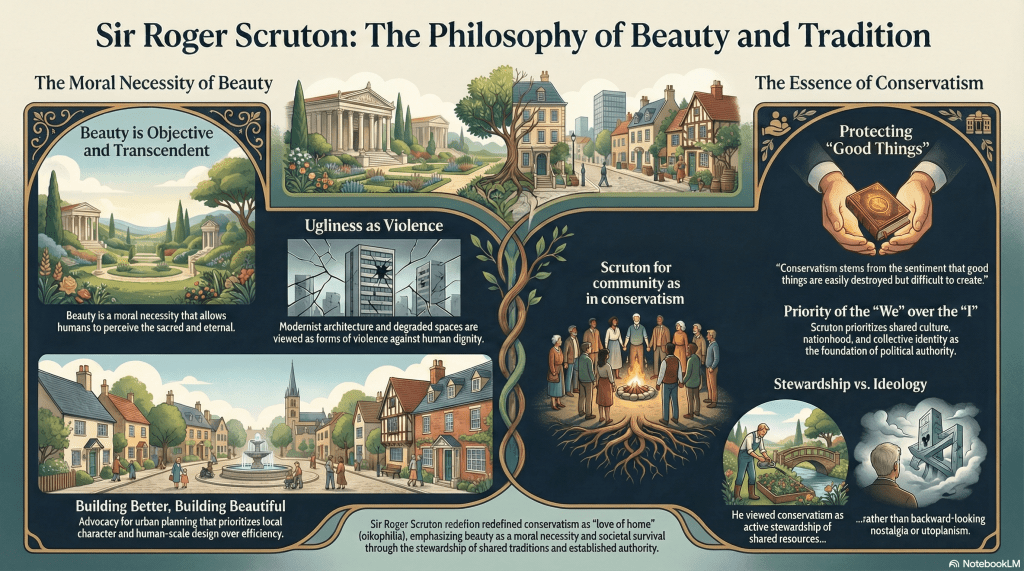

The Quest for Beauty

To Roger Scruton beauty is objective, transcendent, and morally essential rather than merely subjective preference. He argues that beauty functions as “a glimpse of the transcendental,” a way for mortal beings to perceive something eternal and to stand “in the presence of the sacred without needing theology.” Scruton insists that genuine beauty differs fundamentally from mere prettiness—while prettiness is consumable and serves the observer’s pleasure, beauty demands recognition and makes an objective claim on us. He contends that experiencing natural beauty “contains a reassurance that this world is a right and fitting place to be—a home in which our human powers find confirmation,” and that aesthetic judgment reveals genuine truths about reality through a mode of knowing that argument alone cannot reach.

Scruton transforms beauty from an optional luxury into a moral obligation and necessity for human dignity and flourishing. He argues that allowing ugliness to dominate our environments—whether through brutalist architecture, degraded public spaces, or contempt for classical design—constitutes “a form of violence against human dignity.” Beauty in architecture, art, and shared spaces creates homecoming and social cohesion, fostering the bonds that hold communities together. For Scruton, defending beauty becomes defending the sacred itself; we bear a moral duty to create and preserve beautiful things not as elitist preferences but as essential nourishment for human souls and as a resistance against modernity’s impoverishment of meaning, transcendence, and spiritual orientation.

| Building Better, Building Beautifully Scruton supported public policies that promote traditional and aesthetically beautiful architecture in urban planning and housing development, as exemplified in his chairmanship of the UK’s “Building Better, Building Beautifully Commission” in 2018. This initiative aimed to reform building regulations and incentives to prioritize beauty, local character, and human-scale design over purely functional or modernist approaches. It reflected his anti-rationalism in rejecting technocratic and vertical urban planning based on abstract efficiency and rationalist ideologies (such as those inspired by Le Corbusier), favoring instead organic traditions and cultural biases that foster a sense of belonging and continuity with the past. (read more at https://www.gov.uk/government/groups/building-better-building-beautiful-commission) In the United States, in his manifesto “A Plea for Beauty: A Manifesto for a New Urbanism,” Scruton argues that the decline of American cities, which corrodes their social, cultural, economic, and political vitality, stems primarily from the ugliness of their centers and the failure of both market solutions and centralized master planning to promote attractive urban environments. He argues that urban renewal requires secondary aesthetic constraints—limits on height, scale, materials, and architectural details—to ensure that new buildings harmonize with existing ones, reducing uncontrolled urban sprawl and creating urban centers that attract middle-class residents, similar to prosperous European cities like Paris and Florence. Based on examples such as the broken windows theory, in which initial neglect generates further deterioration, Scruton posits that beauty, as a non-instrumental end, encourages people to live, work, and socialize in urban centers, thus revitalizing public life and preventing the degeneration of urban spaces into mere commercial districts or abandoned vacant lots. (available at https://www.aei.org/research-products/report/a-plea-for-beauty-a-manifesto-for-a-new-urbanism/) |

The Meaning of Conservatism

In The Meaning of Conservatism (1980), Roger Scruton redefines conservatism as a coherent philosophy fundamentally grounded in the preservation of tradition, authority, and inherited institutions rather than as rigid market ideology or reactionary resistance to change. Scruton argues that society coheres through established rules and authority, with genuine freedom emerging paradoxically through obedience to social order rather than its rejection. He contends that traditions and institutions embody accumulated wisdom from previous generations that cannot be replaced through abstract rational design, making respect for the past essential to good governance. The work distinguishes conservatism from both progressive utopianism, which Scruton saw as dangerously revolutionary, and from economic libertarianism, arguing instead that conservatives must balance free enterprise with a broader social ethic that subordinates business interests to cultural and moral considerations.

| Michael Oakeshott and Roger Scruton shared foundational elements in their conservative philosophies | |

| Similarity | Description |

| Hegelian Influence and Shared Cultural Frameworks | Both recognize the centrality of inherited, shared modes of experience and view a cultural and institutional framework as an indispensable precondition for civilized life. |

| Anti-Rationalism in Politics | They critique rationalism, preferring tradition and practical knowledge over ideological abstractions or Enlightenment confidence in reason to improve the world. |

| Emphasis on Intermediary Institutions | Both highlight the role of social institutions (e.g., family, property) in shaping moral identity and freedom, rejecting abstract individualism. |

| Conservatism as Disposition | They see conservatism more as a practical disposition or attitude—preferring the familiar and tried—rather than a strict ideology or set of doctrines. |

| Value of Tradition and Social Order | Both value tradition as a source of stability and meaning, with society seen as an inheritance to be preserved and passed on, involving shared experiences and order. |

Central to Scruton’s thesis is his emphasis that people naturally possess limited loyalties centered on their own communities and nations, making loyalty to one’s country essential for legitimate political authority. He critiques postmodernism’s relativistic rejection of transcendent truth, contending that such thinking corrodes the foundations of Western civilization. Rather than viewing conservatism as static defense of the status quo, Scruton presents it as active stewardship of shared resources—social, cultural, economic, and spiritual—that must be thoughtfully preserved and adapted to changing circumstances. This philosophical framework positions conservatism not as backward-looking nostalgia but as a prudent defense of proven institutions and moral order against ideological experimentation that threatens human dignity and social stability.

| Michael Oakeshott and Roger Scruton divergences in focus, application, and implications of conservatism | ||

| Aspect | Michael Oakeshott | Roger Scruton |

| Primary Focus of Conservatism | Emphasizes individual liberty and enabling people to pursue their own enterprises, with conservatism as a means to restrict the state to negative laws for peaceful coexistence. | Focuses on preserving shared culture, nationhood, and collective identity as a rearguard action against threats like liberalism and progressivism, prioritizing the “we” before the “I.” |

| Role of the State | Views governing as a limited activity to “keep the boat afloat,” avoiding positive purposes like wealth creation or welfare, with minimal intervention for orderly conduct. | Sees the state as having obligations to citizens, actively defending cultural inheritance and authority, without automatic hostility but with a role in repelling threats to order and tradition. |

| Approach to Tradition and Culture | Treats tradition procedurally to maintain liberty and inherited legal processes, without emphasizing collective defense or consensus on cultural elements. | Views tradition as a collective inheritance to energetically defend against ideological attacks, deriving values, meanings, and standards from social frameworks like language and religion. |

| View on Corporate Personality | Rejects corporate personality, emphasizing plurality and individuality over holistic or organic views of society and state. | Revives corporate personality, seeing the state and institutions as moral persons with accountability, rooted in Idealism and jurisprudence. |

| Philosophical Style and Engagement | Quiet, dispassionate academic focused on philosophy, avoiding public debate and viewing conservatism as contingent and non-ideological. | Pugilistic public intellectual actively battling cultural and political enemies, with a more dogmatic and activist conservatism. |

| Historicism and Relativism | More historicist, leading to relativist tendencies that prioritize the present and existing arrangements without strong substantive claims for conservation. | Assumes permanent things and values inform history, providing a non-relativist foundation for conserving cultural and aesthetic elements. |

Thinkers of the New Left

Roger Scruton’s Thinkers of the New Left (1985), revised as Fools, Frauds and Firebrands (2015), is a sustained polemic against major postwar leftist intellectuals—Sartre, Foucault, Habermas, Althusser, Lacan, Deleuze, Badiou, Žižek, and others—whom he accuses of promoting obscurantist jargon, relativism, and anti‑Western sentiment. Drawing on his experience with dissidents in communist Czechoslovakia, Scruton traces a genealogy of New Left thought (arranged under headings like “Resentment in Britain,” “Nonsense in Paris,” and “Culture Wars Worldwide”) and argues these thinkers trade philosophical rigor for utopian projects that undermine truth, morality, and social order.

Central to Scruton’s critique is the charge of “moral asymmetry”: the Left’s appropriation of moral language while applying double standards to Western institutions and excusing totalitarian abuses. He contends Marxist and post‑structuralist currents foster resentment, political correctness, deconstruction, and cultural fragmentation—eroding family, nation, religion, and aesthetic values. In the revised edition he updates this critique for identity politics and multiculturalism, denounces the “newspeak” that masks power claims, and urges a return to intellectual rigor and the preservation of communal bonds and objective values.

| Extensive Welfare State Programs Roger Scruton opposed policies that expanded the welfare state in ways he believed created dependency and a socially dysfunctional underclass. This opposition stemmed from his critique of socialism and modern liberalism, which he saw as promoting resentment, egalitarianism, and central planning at the expense of individual responsibility and traditional social structures. Scruton argued that such policies disrupted the organic bonds of society—rooted in customs, institutions, and mutual obligations—by fostering a culture of entitlement that weakened family ties, community self-reliance, and moral virtues like obedience and piety. Instead, he favored market mechanisms tempered by conservative values, where poverty alleviation occurs through localized initiatives like microloans for small businesses, rather than top-down state interventions that he believed perpetuated cycles of dysfunction and eroded the rule of law. |

Key Quotes

“Conservatism starts from a sentiment that all mature people can readily share: the sentiment that good things are easily destroyed, but not easily created.” (How to be a Conservative)

“Intellectuals are naturally attracted by the idea of a planned society, in the belief that they will be in charge of it.” (Fools, Frauds and Firebrands: Thinkers of the New Left)

“A writer who says that there are no truths, or that all truth is ‘merely relative,’ is asking you not to believe him. So don’t.” (Modern Philosophy: An Introduction and Survey).

“Conservatism is more an instinct than an idea. But it’s the instinct that I think we all ultimately share, at least if we are happy in this world. It’s the instinct to hold on to what we love, to protect it from degradation and violence and to build our lives around it.” (The Future of Conservatism)

“The doctrine of original sin, which is contained in the story of Genesis – one of the most beautiful concentrated metaphors in existence – is about the way we human beings fall from treating each other as subjects to treating each other as objects. Love, respect and forgiveness come from that. When we treat each other as objects, then we get the concentration camps.” (The Soul of the World)

“It is not the truth of Marxism that explains the willingness of intellectuals to believe it, but the power that it confers on intellectuals, in their attempts to control the world. And since…it is futile to reason someone out of a thing that he was not reasoned into, we can conclude that Marxism owes its remarkable power to survive every criticism to the fact that it is not a truth-directed but a power-directed system of thought.” (A Political Philosophy)

Questions for reflection

1. How does Scruton’s idea of “oikophilia” (love of home) inform conservative approaches to environmental conservation? Or does it affect the notion that public works should aim to beautify cities?

2. In Scruton’s philosophy, how does religion provide a foundation for morality, and what implications does this have for secular societies facing ethical dilemmas like euthanasia?

3. How might Scruton’s emphasis on “duty, loyalty, and gratitude” as central to political life address contemporary concerns about social fragmentation and declining civic participation?

4. Scruton criticizes postmodernism for promoting relativism and rejecting objective truth. How does this critique bear on contemporary debates about misinformation and epistemological pluralism?

5. Scruton contends that modernity has broken our sense of continuity with nature and cultural inheritance, with modern art often celebrating ugliness. Can contemporary art and architecture be rehabilitated according to his framework, or is the damage irreversible?

6. How did Scruton defend traditional marriage and family structures, and how might this perspective address modern issues like declining birth rates?

7. What insights does Scruton’s philosophy offer on the alienation caused by remote work and digital lifestyles in post-pandemic societies?

8. Scruton argues that “true freedom comes from obedience” to authority and the rule of law. How similar or different is his concept from Montesquieu’s: “…political liberty does not consist in an unlimited freedom. In governments, that is, in societies directed by laws, liberty can consist only in the power of doing what we ought to will, and in not being constrained to do what we ought not to will.“

9. Scruton supported constitutional monarchy as a force for stability and peace, viewing it as transcending daily politics. What relevance does this argument have in republics or in monarchies facing legitimacy crises?

10. If Scruton is correct in asserting that multiculturalism and identity politics fragment the sense of national belonging, what institutional or cultural measures could maintain or restore what he calls “common identity and national heritage” without constituting ethnic or cultural exclusivism?

Leave a comment