Russell Kirk (1918–1994) was an American political philosopher, considered one of the most important figures in the American conservatism.

Figure: Russell Kirk

Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Kirk_1962.jpg

Born in Plymouth, Michigan, he earned his doctorate from the University of St. Andrews in Scotland and spent much of his early career as a professor at Michigan State University. Kirk was a prolific writer, authoring over 30 books, founding influential journals like Modern Age and The University Bookman, and contributing thousands of columns and essays to outlets such as National Review. He lived a reclusive, nocturnal life at his ancestral home in Mecosta, Michigan, where he hosted seminars and mentored young conservatives until his death in 1994.

Politically, he supported Barry Goldwater’s 1964 presidential campaign but viewed himself primarily as a man of letters rather than an activist, emphasizing moral and cultural dimensions over partisan politics. Kirk critiqued ideologies across the spectrum, including unrestrained capitalism, libertarianism (which he saw as promoting “social atomism”), and socialism, arguing that true conservatism rejects all forms of fanaticism and ideology in favor of prudence, natural law, and inherited wisdom.

Kirk’s most influential work is The Conservative Mind: From Burke to Eliot, first published in 1953 as an expansion of his doctoral dissertation.

| Russell Kirk on Rationalism in politics Russell Kirk’s opposition to rationalism in politics stemmed from his belief that it prioritized abstract reasoning over the accumulated wisdom of tradition and experience. He argued that rationalism presupposed that human reason could conceive of perfect social systems, disregarding the complexities of human nature and society. Kirk believed that this approach led to the rejection of historical customs and institutions that had proven their value over time. He saw rationalism as inherently utopian, often resulting in unintended consequences when applied to political and social reforms. For Kirk, genuine conservatism required humility in recognizing the limits of human reason, relying instead on the guidance of established traditions and moral order. Kirk argued that rationalism undermined the social fabric by promoting radical changes based on theoretical ideals rather than practical wisdom. He emphasized the importance of preserving “the permanent things”—the enduring elements of human experience that provide stability and meaning. By relying solely on reason, rationalists neglected the moral and spiritual dimensions of life, which Kirk considered crucial for a healthy society. He believed that politics should be based on respect for historical continuity and the recognition of transcendent truths, rather than the pursuit of abstract, rationalistic designs for society. This opposition to rationalism highlighted Kirk’s commitment to a conservative philosophy rooted in tradition, community, and moral imagination. He warns that rationalism erodes the “prejudices” (deep-seated convictions shaped by generations) that provide social cohesion, leading to ideologies that prioritize individual autonomy or state planning at the expense of community ties and divine order. Instead of rationalistic designs, Kirk advocates for a conservatism based on organic development, where change occurs gradually and in harmony with inherited institutions, rejecting the Enlightenment’s emphasis on progress, secularism, and rationality as simplistic and ultimately destructive. This position distinguishes Kirk’s thought from what he calls “conservative rationalism,” which may incorporate reason tempered by tradition, but he firmly opposes unbridled rationalism as a symptom of cultural decay that undermines the moral and imaginative foundations essential for a just society. |

This book traces the development of conservative thought in the Anglo-American tradition, starting with Edmund Burke and extending to figures like T.S. Eliot. It highlights contributions from statesmen (e.g., John Adams, Alexander Hamilton, Benjamin Disraeli), writers (e.g., Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Irving Babbitt), and thinkers (e.g., Alexis de Tocqueville, John Henry Newman).

Kirk positions conservatism as a moral and imaginative disposition—a “negation of ideology”—rooted in religious faith, poetry, tradition, and the “politics of prudence,” rather than in economics or abstract theory. He contrasts it sharply with liberalism’s faith in human perfectibility, rapid change, secularism, and rejection of tradition, as well as with other modern “errors” like collectivism, atomistic individualism, industrialism, and mass society.

| Russell Kirk on Goldwater’s fusionism Russell Kirk’s stance on Goldwater’s fusionism (read about this topic in the next chapter) was characterized by skepticism and philosophical opposition, despite his practical involvement in the campaign. Fusionism attempted to unite libertarian and traditionalist conservatism. Kirk opposed fusionism because he believed it attempted to reconcile fundamentally incompatible worldviews—libertarianism and traditionalist conservatism. He argued that libertarianism’s emphasis on individual freedom and rationalism conflicted with the core conservative principles of transcendent moral order, religious faith, and respect for tradition. Kirk saw these elements as essential to genuine conservatism, while libertarianism prioritized individual choice over communal values and historical wisdom. This philosophical divergence, he felt, could not be resolved through fusionism’s ideological synthesis, which he viewed as undermining the integrity and coherence of the conservative movement. Despite these objections, Kirk engaged with Goldwater’s campaign, recognizing the pragmatic necessity of coalition-building in the conservative movement. Kirk believed compromising on foundational conservative principles would undermine the movement’s credibility. However, his strategic involvement in Goldwater’s campaign illustrated a willingness to engage pragmatically with the broader conservative coalition, despite ideological differences. This tension between maintaining philosophical purity and achieving political viability reflects a broader challenge within American conservatism, as the ideological divide between libertarian and traditionalist elements continues to influence the movement’s trajectory. |

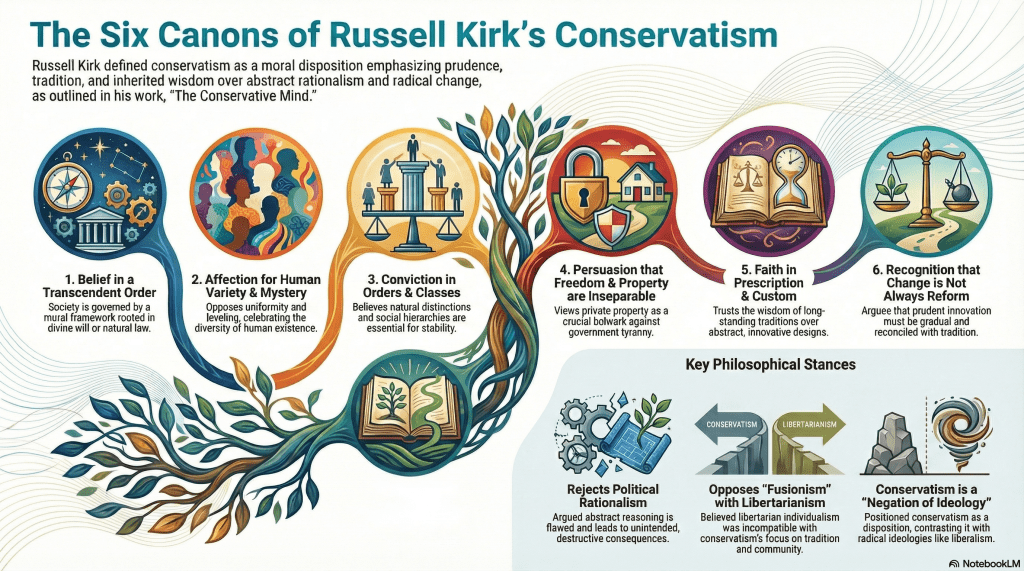

At the heart of Kirk’s ideas are six “canons” of conservative thought, which he outlines early in the book as guiding principles. These are not rigid dogmas but a synthesis of enduring values drawn from historical conservatives:

- Belief in a transcendent order: Society is governed by a moral framework based on divine revelation, natural law, or ancient tradition, rather than human invention alone.

- Affection for the variety and mystery of human existence: Conservatism celebrates diversity in customs, classes, and individual differences, opposing uniformity or leveling. en.wikipedia.org

- Conviction that civilized society requires orders and classes: Natural distinctions and hierarchies are essential for social stability, rejecting egalitarian flattening. en.wikipedia.org

- Persuasion that freedom and property are inseparably connected: Private property is a bulwark against tyranny and a foundation for personal liberty. en.wikipedia.org

- Faith in prescription (custom, convention, and old usage): Long-standing practices and institutions carry more wisdom than rationalist innovations. en.wikipedia.org

- Recognition that change may not be salutary reform: Prudent innovation must be gradual and reconciled with traditions, avoiding hasty or radical alterations. en.wikipedia.org

These canons emphasize reverence for ancestors, responsibility to future generations, the role of imagination and poetry in politics, and the dangers of hubris or unchecked progress.

Kirk’s work remains a cornerstone text, reprinted in multiple editions and languages, for understanding conservatism as a timeless defense of order, virtue, and the human soul against the excesses of modernity.

| The conservative ability to reshape one’s beliefs to adapt to the times. Mike Lee (U.S. Senator from Utah), in his speech “What’s Next for Conservatives” at the Heritage Foundation on October 29, 2013, said: By 1977, the Republican Party was in disarray. The party establishment had been discredited by political failure and policy debacles, foreign and domestic. A new generation of grassroots conservatives was rising up to challenge the establishment. The culmination of that challenge was Ronald Reagan’s 1976 primary campaign against a far-less conservative, establishment incumbent. That campaign failed, of course, and was derided by Washington insiders as a foolish “civil war” that ultimately served only to elect Democrats. In other words, we have been here before. And of course, we know now that Reagan and the conservative movement were vindicated in 1980. So it is tempting for conservatives today to believe that history is on the verge of repeating itself, that our struggles with the Republican establishment are only a prelude to pre-ordained victory and that our own vindication – our generation’s 1980 – is just around the corner. But there is still a piece missing, a glaring difference between the successful conservative challenge to the Washington establishment in the late 1970s, and ourchallenge to the establishment today. Much of the difference can be found in what happened between 1976 and 1980 – the hard, heroic work of translating conservatism’s bedrock principles into new and innovative policy reforms. In The Conservative Mind, Russell Kirk observed that “conservatives inherit from [Edmund] Burke a talent for re-expressing their convictions to fit the time.” That is precisely what the conservatives of the late 1970s did. The ideas that defined and propelled the Reagan Revolution did not come down from a mountain etched in stone tablets, they were forged in an open, roiling, diverse debate about how conservatism could truly meet the challenges of that day. That debate invited all conservatives and as we know, elevated the best. (full speech at https://www.lee.senate.gov/2013/10/what-s-next-for-conservatives) |

Selected text

RUSSELL KIRK. THE CONSERVATIVE MIND. From Burke to Eliot. 1953.

The Idea of Conservatism

(…)

Any informed conservative is reluctant to condense profound and intricate intellectual systems to a few pretentious phrases; he prefers to leave that technique to the enthusiasm of radicals. Con servatism is not a fixed and immutable body of dogmata; conservatives inherit from Burke a talent for reexpressing their convictions to fit the time. As a working premise, nevertheless, one can observe here that the essence of social conservatism is preservation of the ancient moral traditions of humanity. Conservatives respect the wisdom of their ancestors (this phrase was Strafford’s, and Hooker’s, before Burke illuminated it); they are dubious of wholesale alteration. They think society is a spiritual reality, possessing an eternal life but a delicate constitution: it cannot be scrapped and recast as if it were a machine. “What is conservatism?” Abraham Lincoln inquired once. “Is it not adherence to the old and tried, against the new and untried?” It is that, but it is more. F.J.C. Hearnshaw, in his Conservatism in England, lists a dozen principles of conservatives, but possibly these may be comprehended in a briefer catalogue. I think that there are six canons of conservative thought

(1) Belief in a transcendent order, or body of natural law, which rules society as well as conscience. Political problems, at bottom, are religious and moral problems. A narrow rationality, what Coleridge called the Understanding, cannot of itself satisfy human needs. “Every Tory is a realist,’ says Keith Feiling: “he knows that there are great forces in heaven and earth that man’s philosophy cannot plumb or fathom. “3 True politics is the art of apprehending and applying the justice which ought to prevail in a community of souls.

(2) Affection for the proliferating variety and mystery of human existence, as opposed to the narrowing uniformity, egalitarianism, and utilitarian aims of most radical systems; conservatives resist what Robert Graves calls “Logicalism” in society. This prejudice has been called “the conservatism of enjoyment”-a sense that life is worth living, according to Walter Bagehot “the proper source of an animated Conservatism.”

(3) Conviction that civilized society requires orders and classes, as against the notion of a “classless society.” With reason, conservatives often have been called “the party of order.” If natural distinctions are effaced among men, oligarchs fill the vacuum. U1-timate equality in the judgment of God, and equality before courts of law, are recognized by conservatives; but equality of condition, they think, means equality in servitude and boredom.

(4) Persuasion that freedom and property are closely linked: separate property from private possession, and Leviathan becomes master of all. Economic levelling, they maintain, is not economic progress. (5) Faith in prescription and distrust of “sophisters, calculators, and economists” who would reconstruct society upon abstract designs. Custom, convention, and old prescription are checks both upon man’s anarchic impulse and upon the innovator’s lust for power.

(6) Recognition that change may not be salutary reform: hasty innovation may be a devouring conflagration, rather than a torch of progress. Society must alter, for prudent change is the means of social preservation; but a statesman must take Providence into his calculations, and a statesman’s chief virtue, according to Plato and Burke, is prudence.

Various deviations from this body of opinion have occurred, and there are numerous appendages to it; but in general conservatives have adhered to these convictions or sentiments with some consistency, for two centuries. To catalogue the principles of their opponents is more difficult. At least five major schools of radical thought have competed for public favor since Burke entered politics: the rationalism of the philosophes, the romantic emancipation of Rousseau and his allies, the utilitarianism of the Benthamites, the positivism of Comte’s school, and the collectivistic materialism of Marx and other socialists. This list leaves out of account those scientific doctrines, Darwinism chief among them, which have done so much to undermine the first principles of a conservative order. To express these several radicalisms in terms of a common denominator probably is presumptuous, foreign to the philosophical tenets of conservatism. All the same, in a hastily generalizing fashion one may say that radicalism since 1790 has tended to attack the prescriptive arrangement of society on the following grounds.

(1) The perfectibility of man and the illimitable progress of society: meliorism. Radicals believe that education, positive legislation, and alteration of environment can produce men like gods; they deny that humanity has a natural proclivity toward violence and sin.

(2) Contempt for tradition. Reason, impulse, and materialistic determinism are severally preferred as guides to social welfare, trustier than the wisdom of our ancestors. Formal religion is rejected and various ideologies are presented as substitutes.

(3) Political levelling. Order and privilege are condemned; total democracy, as direct as practicable, is the professed radical ideal. Allied with this spirit, generally, is a dislike of old parliamentary arrangements and an eagerness for centralization and consolidation.

(4) Economic levelling. The ancient rights of property, especially property in land, are suspect to almost all radicals; and collectivistic reformers hack at the institution of private property root and branch

As a fifth point, one might try to define a common radical view of the state’s function; but here the chasm of opinion between the chief schools of innovation is too deep for any satisfactory generalization. One can only remark that radicals unite in detesting Burke’s description of the state as ordained of God, and his concept of society as joined in perpetuity by a moral bond among the dead, the living, and those yet to be born-the community of souls.

(…)

Questions for reflection

1. Kirk argued that conservatism requires belief in “an enduring moral order” grounded in “tradition, divine revelation, or natural law,” yet modern society increasingly rejects any universal standards, treating morality as culturally constructed and subjective. Can Kirk’s framework provide a coherent alternative to this relativism, or does his dependence on transcendent principles alienate conservatives from secular intellectual movements?

2. Kirk championed “a disposition to preserve and an ability to improve, taken together,” arguing that sudden reforms produce unintended consequences. Yet technological acceleration and social transformation seem to demand rapid policy responses; does Kirk’s conservatism offer practical wisdom for navigating genuine crises, or does it counsel passivity in the face of unprecedented technological disruption and rapid institutional change?

3. Kirk argued that “society requires orders and classes that emphasize natural distinctions”. How can contemporary conservatives adopt Kirk’s principle of natural variety without appearing to defend genuine injustice or to oppose legitimate democratic expansion?t appearing to defend genuine injustice or to oppose legitimate democratic expansion?

4. Kirk believed that “the human need for community is no less pressing than the need for food or shelter” and that communities require local decision-making grounded in “general agreement of those affected.” Can his concept of territorial democracy provide a framework for addressing contemporary regionalism, urban-rural divides, and the loss of local authority to centralized bureaucratic power?

5. Kirk argued that libertarians “bear no authority, temporal or spiritual” and lack commitment to “ancient beliefs and customs,” placing them fundamentally at odds with traditional conservatism. Has the fusion of libertarian and conservative thought, which Kirk rejected, proven unstable and uncapable of solving political and societal problemas? Is it still viable today?

6. Kirk criticized those who would remake society according to abstract ideals without deference to tradition or consideration of unintended consequences. Do contemporary progressive movements for gender ideology, historical reinterpretation, and institutional transformation exemplify the dangers Kirk identified, or does his framework unfairly dismiss legitimate reform efforts?

7. Kirk believed that “the moral imagination is the power of ethical perception that discerns and aspires toward right action” and that imaginative literature conveyed truths that philosophical treatises could not. Can Kirk’s humanistic approach to moral formation survive in an age of algorithmic content delivery and entertainment designed for engagement rather than wisdom?

8. Kirk maintained an uncompromising position that Christianity and Western civilization were “unimaginable apart from one another.” Does contemporary secularization vindicate his pessimism about cultural decline, or has secular civilization proven more resilient than Kirk anticipated?

9. Kirk embodied his philosophy through his home at Piety Hill, where he and his wife practiced Christian charity and community responsibility. How can Kirk’s vision of lived conservatism—grounded in religious faith, family stability, local community participation, and hospitality—be transmitted and practiced in a mobile, digitally connected, economically precarious society where traditional institutions have weakened?

Leave a comment