Introduction

Justice Antonin Scalia, who served as an Associate Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court from 1986 until his death in 2016, was renowned for his conservative judicial philosophy that emphasized fidelity to the Constitution and statutes as they were originally understood. Below, I’ll outline his main ideas, drawing from his writings, opinions, and scholarly analyses.

Figure 40. Justice Antonin Scalia,

Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Antonin_Scalia_Official_SCOTUS_Portrait.jpg

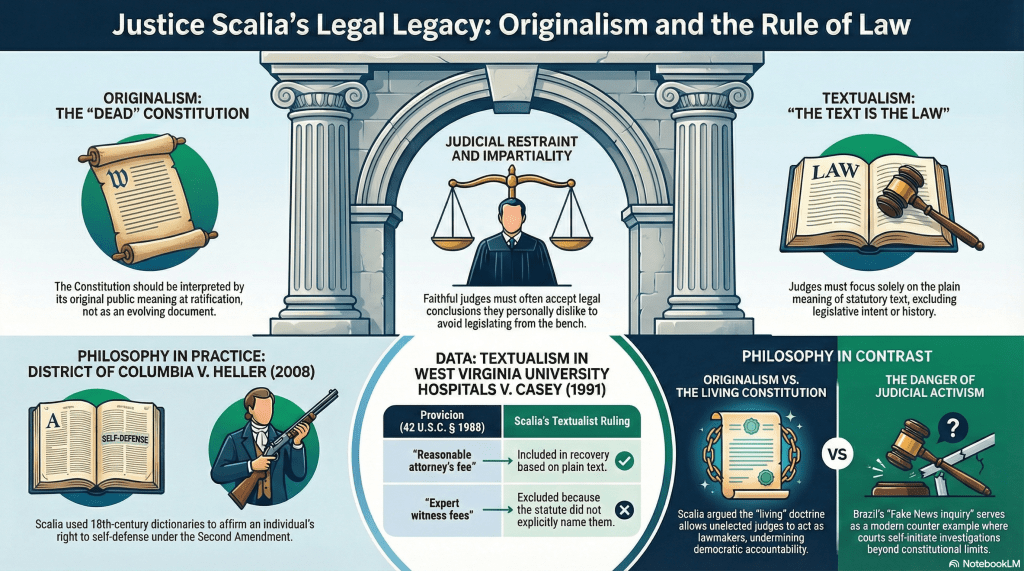

Originalism

Scalia was the leading proponent of originalism, the theory that the Constitution should be interpreted according to its original public meaning at the time it was ratified. He argued that this approach prevents judges from imposing their own policy preferences and ensures democratic accountability, as changes to the Constitution should come through amendments rather than judicial reinterpretation. He famously criticized the “living Constitution” doctrine, which views the document as evolving with societal changes, calling it a threat to the rule of law because it allows unelected judges to act as lawmakers.

| District of Columbia v. Heller (2008) A prominent example of interpreting the U.S. Constitution based on its original public meaning at the time of ratification is District of Columbia v. Heller (2008), where Scalia authored the majority opinion. The case challenged a D.C. law that banned handgun possession in the home and required firearms to be kept unloaded and disassembled or bound by a trigger lock. The issue centered on the Second Amendment: “A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed.” Scalia applied originalism by extensively examining historical sources, including 18th-century dictionaries, state constitutions, and contemporary writings, to determine the amendment’s meaning when ratified in 1791. He concluded that the amendment protects an individual’s right to possess firearms for traditionally lawful purposes, such as self-defense in the home, unconnected to militia service. This historical analysis showed that the prefatory clause (“A well regulated Militia…“) announces a purpose but does not limit the operative clause (“the right of the people to keep and bear Arms…“). Scalia emphasized that the Constitution is “enduring” and means today what it meant when adopted, rejecting arguments that it should evolve with changing views on gun control. The Court struck down the D.C. ban, marking a landmark victory for individual gun rights grounded in original meaning. |

Textualism

For statutory interpretation, Scalia championed textualism, insisting that judges should focus solely on the plain meaning of the text as understood by reasonable people at the time of enactment, without delving into legislative history or intent. He believed this method promotes predictability and curbs judicial overreach, as it treats laws as fixed rules rather than vague standards open to manipulation. In his view, textualism is constitutionally mandated, and deviations from it undermine the separation of powers.

| West Virginia University Hospitals, Inc. v. Casey (1991) An illustrative case of textualism is West Virginia University Hospitals, Inc. v. Casey (1991), where Scalia wrote the majority opinion. The dispute arose under 42 U.S.C. § 1988, a civil rights statute allowing prevailing parties to recover “a reasonable attorney’s fee as part of the costs” in certain lawsuits. West Virginia hospitals sued Pennsylvania officials over reimbursement for treating indigent patients, won, and sought to recover not only attorney’s fees but also expert witness fees. Scalia employed textualism by strictly adhering to the plain language: the statute mentions “attorney’s fee,” not “expert witness fee.” He used the “whole code” canon, comparing § 1988 to over 30 other federal statutes where Congress explicitly included expert fees alongside attorney’s fees when intended. This textual comparison led him to conclude that Congress deliberately omitted expert fees from § 1988, reasoning that if such fees were meant to be covered, the text would say so. Scalia dismissed arguments based on legislative intent or policy, focusing solely on what the enacted words reasonably conveyed to an ordinary reader. The Court ruled that expert fees were not recoverable, exemplifying how textualism promotes predictability and restrains judicial discretion. |

Judicial Restraint and the Role of Judges

Scalia stressed that judges must interpret law, not create it, to preserve democracy and the proper balance of government branches. He advocated for judicial restraint, warning against the “common law mindset” that treats precedents as malleable, which he saw as a post-realist error leading to activist judging. His philosophy often led him to conservative outcomes, such as supporting states’ rights and dissenting in cases like Planned Parenthood v. Casey, where he argued there is no constitutional right to abortion.

Rule of Law, Separation of Powers, and Federalism

A core tenet was the importance of clear, predictable rules over flexible standards, which he believed upholds the rule of law and protects individual liberties. Scalia was a strong defender of separation of powers and federalism, arguing that these principles limit federal overreach and empower states. He also emphasized historical context and text in First Amendment cases, balancing free speech with other constitutional values.

Scalia’s ideas influenced generations of legal scholars and judges, inspiring coherent philosophies like textualism and originalism, even if his conservative views sometimes failed to sway majorities on the Court.

An assessment of his legacy depends on the evaluator’s political and social position. On the one hand, ordinary citizens and right-wing admirers praise his restraint and commitment to democratic principles, and on the other, judges, lawyers, and left-wing critics see him as an obstacle to their desire for an activist judiciary in which their respective groups gain power illegitimately, disregarding and usurping the role of the legislature.

| The Brazilian Supreme Federal Court’s “Fake News Inquiry” (Inquérito 4.781) One prominent example of a Brazilian Supreme Federal Court (STF) decision that exemplifies judicial activism contrary to an originalist interpretation (while showing bias in favor of the government) is the initiation and ongoing handling of Inquérito 4.781, commonly known as the “Fake News Inquiry.” Launched in March 2019 by then-STF President José Antonio Dias Toffoli, this inquiry empowered the STF to investigate and prosecute alleged dissemination of fake news, slander, defamation, and threats directed at the court, its ministers, and their families. Under Minister Alexandre de Moraes as rapporteur since its inception, the inquiry has led to sweeping actions including account suspensions on social media platforms like X (formerly Twitter), Facebook, and Instagram; searches and seizures; arrests of critics such as Congressman Daniel Silveira in 2021 for online insults; and even the temporary blocking of entire platforms, as seen in the 2022 suspension of Telegram and the 2024 nationwide ban on X over noncompliance with content removal orders. Why This Is Contrary to Originalist Interpretation Brazil’s 1988 Constitution, drafted post-military dictatorship to emphasize democracy, separation of powers, and individual rights, explicitly assigns investigative and prosecutorial roles to the Public Ministry (Ministério Público) under Article 129, while limiting the judiciary to adjudication in an adversarial system (Articles 2 and 5). The STF justified the inquiry under Article 43 of its Internal Regulations, claiming authority to probe crimes against its honor or security—but critics argue this internal rule cannot override the Constitution’s clear allocation of powers, nor does the original text envision the court self-initiating broad, inquisitorial probes without external oversight. In a 10-1 decision in June 2020 upholding the inquiry (ADPF 572), the STF majority deviated from this textual constraint by invoking “necessity” to protect democracy amid perceived threats, effectively adopting a living constitution approach that allows judicial evolution beyond the framers’ intent. Dissenting Minister Marco Aurélio Mello highlighted this as a violation of impartiality and due process, arguing it creates an unconstitutional “ad hoc tribunal” where the STF acts as victim, investigator, prosecutor, and judge—roles not contemplated in the Constitution’s original design. This activism echoes inquisitorial systems rejected by the 1988 framers, who aimed to prevent authoritarian overreach, and contradicts the STF’s own prior rulings (e.g., ADI 4.693 in 2018) deeming similar state-court practices unconstitutional. Evidence of Bias in Favor of the Government The inquiry has been wielded disproportionately against critics of the STF and political opponents of the ruling government, particularly under President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva since 2023, aligning with leftist administrations that have supported or benefited from Moraes’ actions. Targets have included Bolsonaro allies, journalists, businessmen, and right-wing figures accused of spreading “disinformation” or supporting alleged coup attempts post-2022 elections, with actions like the 2022 investigations into pro-Bolsonaro entrepreneurs and the 2024 inclusion of former President Jair Bolsonaro himself in the probe. In contrast, similar petitions against Lula or his allies (e.g., for false claims) have been handled leniently or ignored, suggesting selective enforcement. Critics, including legal scholars and human rights groups, describe the inquiry as an “inquisitorial attack” on the rule of law, intended to suppress dissent and advance the executive branch’s agenda, such as combating “fake news” without legislative backing (e.g., the stalled “Fake News Bill”). Public trust in the Supreme Court has plummeted, with polls showing only 14% full confidence by 2023, amid accusations of authoritarianism reminiscent of Brazil’s dictatorial past. The inquiry’s expansion of state censorship powers, without constitutional provision, highlights a pro-government bias and institutional self-preservation at the expense of original textual limits. |

Key Quotes

On Textualism

- “Textualism means you are governed by the text. That’s the only thing that is relevant to your decision. Not whether the outcome is desirable, not whether legislative history says this or that. But the text of the statute.”

- “The text is the law.”

On Originalism

- “Originalism says that when you consult the text, you give it the meaning it had when it was adopted, not some later modern meaning.”

- “The Constitution is not a living organism. It is a legal document.“

- “The Constitution is ‘not a living document.’ It’s dead, dead, dead.”

- “Our manner of interpreting the Constitution is to begin with the text, and to give that text the meaning that it bore when it was adopted by the people.”

- “My Constitution is a very flexible Constitution. You think the death penalty is a good idea — persuade your fellow citizens and adopt it. You think it’s a bad idea — persuade them the other way and eliminate it. You want a right to abortion — create it the way most rights are created in a democratic society, persuade your fellow citizens it’s a good idea and enact it. You want the opposite — persuade them the other way. That’s flexibility.”

On Judicial Philosophy and Restraint

- “If you’re going to be a good and faithful judge, you have to resign yourself to the fact that you’re not always going to like the conclusions you reach. If you like them all the time, you’re probably doing something wrong.“

- “The judge who always likes the results he reaches is a bad judge.“

- “A Bill of Rights that means what the majority wants it to mean is worthless.“

- “Words have meaning. And their meaning doesn’t change.”

Questions for reflection

1. What is the core principle of originalism as articulated by Justice Antonin Scalia, and how does it differ from the “living Constitution” approach?

2. Why did Scalia argue that the Constitution is “dead, dead, dead,” and how does this phrase encapsulate his rejection of evolving interpretations?

3. What role does historical context play in originalism, and why did Scalia argue it is essential for constitutional fidelity?

4. How did Scalia apply originalism in his majority opinion in District of Columbia v. Heller, particularly regarding the Second Amendment’s historical meaning?

5. How could originalism be applied to contemporary issues like digital privacy under the Fourth Amendment?

6. Provide an example from Scalia’s philosophy where originalism might lead to outcomes that a judge personally dislikes, emphasizing his view on impartiality.

7. How does the Brazilian STF’s “Fake News Inquiry” exemplify a non-originalist approach, and in what ways does it deviate from textual constraints in Brazil’s 1988 Constitution?

8. Explain textualism in the context of statutory interpretation, and why Scalia believed it promotes judicial restraint over activism.

9. In West Virginia University Hospitals, Inc. v. Casey, how did Scalia’s textualist approach lead to the exclusion of expert witness fees from recoverable costs under 42 U.S.C. § 1988?How does originalism ensure democratic accountability, according to Scalia, and what role do constitutional amendments play in this framework?

10. Contrast Scalia’s textualism with the use of legislative history in interpretation, using one of his key quotes to illustrate the point.

11. Using Scalia’s quote, “The text is the law,” discuss how textualism could be applied to a modern statutory dispute, such as one involving ambiguous language in federal regulations.

Leave a comment