Edmund Burke, an Irish-born British statesman and philosopher (1729–1797), served in the British House of Commons and is best known for his opposition to the French Revolution. Burke’s Reflections on the Revolution in France (1790) is a seminal work in political philosophy and a cornerstone of modern conservatism. Written as a response to the French Revolution and the revolutionary enthusiasm, Burke articulates a critique of radical change and a defense of tradition, gradual reform, and practical wisdom.

Figure 35. Edmund Burke

Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:EdmundBurke1771.jpg

Reflections was initially composed as a letter, ostensibly addressed to a French correspondent, but aimed at influencing the British public, whom he feared might emulate the revolution’s radical politics. The work sparked significant debate, and remains a classic text in political theory, history, and literature.

Main Ideas and Detailed Explanation

- Conservatism and Tradition:

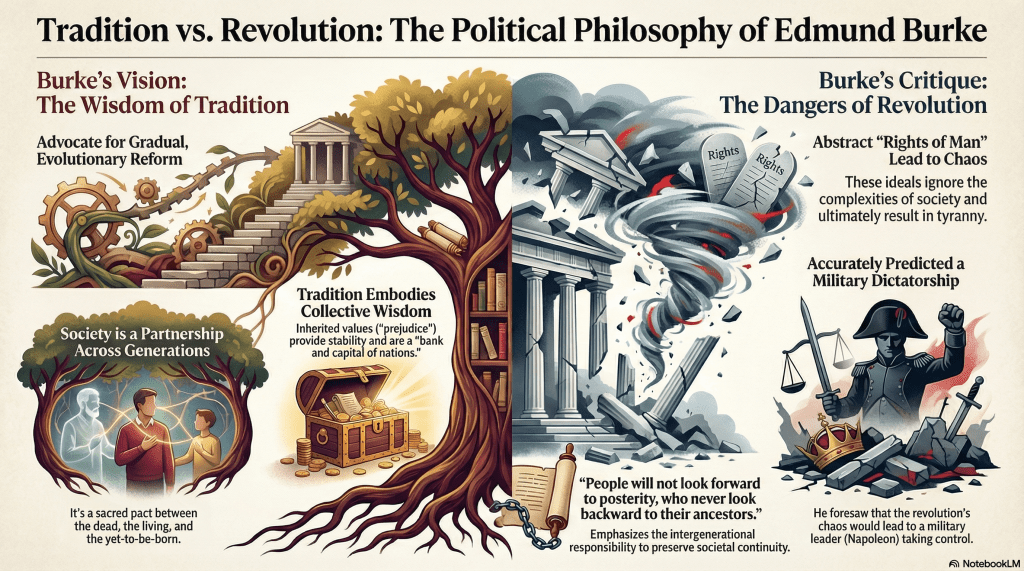

- Burke is widely regarded as the father of modern conservatism, transforming traditionalism into a self-conscious political philosophy. He argues that society and government should be based on inherited traditions and institutions, as seen in his praise for the British Constitution, which evolved gradually through historical experience.

- He emphasizes the role of “prejudice” (adherence to traditional values without rational basis) as a stabilizing force, stating, “[prejudice] renders a man’s virtue his habit,” drawing from the “general bank and capital of nations and ages”. This reflects his belief that traditions embody collective wisdom, providing stability and continuity.

- Critique of the French Revolution:

- Burke vehemently opposes the French Revolution, viewing it as a dangerous experiment based on abstract ideals like liberty, equality, and the “rights of man.” He argues these principles ignore the complexities of human nature and society, leading to chaos and eventual tyranny.

- He predicts the revolution’s rejection of tradition would dissolve the “pleasing illusions” and “moral imagination” that sustain civilization, resulting in a society ruled by force, such as preventive murder and confiscation”. His prediction of a military dictatorship, fulfilled by Napoleon’s rise on 18 Brumaire (two years after Burke’s death in 1797), underscores his foresight.

- Gradual Reform vs. Radical Change:

- Burke advocates for gradual, constitutional reform rather than revolutionary upheaval. He believes political systems should evolve through practical experience and historical precedent, not sudden, sweeping changes based on theoretical ideals.

- He contrasts the French Revolution with the British Glorious Revolution of 1688, which he supported as a legitimate reform that preserved existing traditions and institutions while addressing specific grievances. This reflects his belief that change should be incremental, building on what works.

- Rights and Duties:

- Burke rejects the notion of abstract, universal rights, seeing them as detached from historical and cultural contexts. Instead, he argues that rights are “entailed inheritances” from forefathers, embedded in specific traditions like the Magna Carta and the Declaration of Rights.

- He insists that rights come with corresponding duties and are not absolute, stating, “there are no rights without corresponding duties, or without some strict qualifications”. This reflects his view that rights are practical benefits derived from living in a well-ordered society, not universal entitlements.

- Society as a Partnership:

- Burke describes society as a “partnership in all science; a partnership in all art; a partnership in every virtue, and in all perfection,” between the living, the dead, and those yet to be born. This partnership is not a temporary contract but a continuous connection across generations, emphasizing the importance of preserving traditions for the future.

- He famously writes, “People who never look back to their ancestors will not look forward to posterity,” highlighting the intergenerational responsibility to maintain societal continuity.

- Role of Manners, Religion, and Moral Imagination:

- Burke underscores the importance of manners, religion, and the moral imagination in maintaining social order and civilization. He believes these elements, often associated with the aristocracy and clergy, provide a framework for virtue and learning.

- He warns that the French Revolution’s rejection of these traditions would lead to a “swinish multitude” and the debasement of learning, with European civilization depending on the “spirit of a gentleman and religion”.

- Practicality over Theory:

- Burke prioritizes practical wisdom and the lessons of history over abstract philosophical theories. He argues that governing is an “experimental science” that requires experience and cannot be reduced to simple, universal principles, stating, “Constructing or renovating a commonwealth is not teachable a priori”.

- He criticizes the French revolutionaries for their reliance on “extravagant and presumptuous speculations” that disregard the intricacies of human nature and society.

- Prediction of Negative Outcomes:

- Burke accurately predicts that the French Revolution’s chaos would lead to a military takeover, with the army becoming mutinous and a “popular general” becoming “master of your assembly, the master of your whole republic”. This was later realized with Napoleon’s rise, validating Burke’s concerns about the dangers of radical change.

| Moral Imagination Edmund Burke’s moral imagination is the human capacity to perceive the moral shape and long-term consequences of actions, institutions, and policies through sympathy, memory, and sympathetic feeling rather than abstract formulae. For Burke it includes several interrelated elements: Respect for tradition and inherited wisdom: the imagination sees political and social arrangements as the product of accumulated moral learning and prudence, not mere conveniences to be redesigned on abstract principles. Sympathy and moral feeling: imagination extends our sympathies across time and among people, enabling us to apprehend the interests, duties, and dignity of others and of future generations. Prudential foresight: it projects the probable consequences of political change, weighing unseen effects and unintended harms; this foresight grounds Burke’s conservative caution about radical reform. Moral taste and sensibility: influenced by his aesthetics (the Sublime and the Beautiful), Burke treats moral judgment as akin to taste—cultivated by literature, religion, and custom, not reducible to pure reason or utility. Moral order and obligation: the imagination apprehends social bonds (filial, civic, religious) that generate obligations and loyalties essential to a stable moral-political order. In short, Burke’s moral imagination is the cultivated power to judge rightly about public life by appreciating tradition, sympathizing with others, and forecasting moral consequences—countering abstract, atomistic theories of society. |

Additional Insights

- Burke’s support for the British and American revolutions, even though he opposed the French revolution, demonstrates that even conservatives defend revolutions, depending on the context. He saw the former as operating within traditions and institutions, while he categorically rejected the latter, suggesting a distinct nature between the Glorious and American revolutions in contrast to the French revolution.

- Burke’s critique of the revolutionary assembly, noting its “poverty of conception, crudeness, vulgarity” and lack of true freedom, underscores his disdain for the radical politics of the French Enlightenment, stemming from intellectuals like Rousseau and Voltaire.

| Tradition and democracy Gilbert Keith Chesterton (1874 – 11936) was an English author and philosopher. In his book Orthodoxy, he explains why, in his view, tradition is a kind of democracy. “Tradition means giving votes to the most obscure of all classes, our ancestors. It is the democracy of the dead. Tradition refuses to submit to the small and arrogant oligarchy of those who merely happen to be walking about. All democrats object to men being disqualified by the accident of birth; tradition objects to their being disqualified by the accident of death.” |

Some Quotes

The following table summarizes key quotes and their relevance to Burke’s main ideas:

| Idea | Quote |

|---|---|

| Tradition and Prejudice | “Prejudice is of ready application in the emergency; it previously engages the mind in a steady course of wisdom and virtue, and does not leave the man hesitating in the moment of decision, sceptical, puzzled, and unresolved. Prejudice renders a man’s virtue his habit; and not a series of unconnected acts. Through just prejudice, his duty becomes a part of his nature.” |

| Critique of French Revolution | “The very idea of the fabrication of a new government is enough to fill us with disgust and horror.” |

| Rights and Duties | “Men have a right to live by that rule; they have a right to do justice, as between their fellows, whether their fellows are in public function or in ordinary occupation.” |

| Society as Partnership | “People will not look forward to posterity, who never look backward to their ancestors” |

| Practicality over Theory | “The science of constructing a commonwealth, or renovating it, or reforming it, is, like every other experimental science, not to be taught a priori.” |

Conclusion

Edmund Burke’s Reflections on the Revolution in France is a defense of tradition, gradual reform, and practical wisdom against the radicalism of the French Revolution. He argues that society must be preserved as an inheritance from past generations, with rights and liberties rooted in historical experience rather than abstract theories. His work remains a cornerstone of conservative political thought, emphasizing the importance of stability, continuity, and the complexities of human nature, and continues to influence debates on political reform and societal change.

| Russell Kirk discusses Edmund Burke. In his classic book The Conservative Mind, the political philosopher Russell Kirk (1918-1994) wrote about Burke: Conservatism, steadily; but conservation of what? Burke stood resolutely for preservation of the British constitution, with its traditional division of powers, a system buttressed in Burke’s mind by the arguments of Hooker and Locke and Montesquieu, as the system most friendly to liberty and order to be discerned in all Europe. And he stood for preservation of the still larger constitution of civilization. Anacharsis Cloots might claim to be the orator of the human race; Burke was the conservator of the species. A universal constitution of civilized peoples is implied in Burke’s writings and speeches, and these are its chief articles: reverence for the divine origin of social disposition; reliance upon tradition and prejudice for public and private guidance; conviction that men are equal in the sight of God, but equal only so; devotion to personal freedom and private property; opposition to doctrinaire alteration. In the Reflections, these beliefs severally find their most burningly earnest expression: (…) A moral order, good old prescription, cautious reform-these are elements not merely English, but of general application; for Burke, they were as valid in Madras as in Bristol; and his French and German disciples, throughout the nineteenth century, found them applicable to Continental institutions. The intellectual system of Burke, then, is not simply a guarding of British political institutions. If it were only this, half his significance for us would be merely antiquarian. Yet a brief glance at the particular Constitution which Burke praised may repay attention-a glance at that eighteenth-century society upon which it rested, and which, in turn, depended upon that political constitution. Recently much nostalgic eulogy has been lavished upon the eighteenth century; but there are sound reasons why modern men may admire that age. The constitution of England existed for the protection of Englishmen in all walks of life, Burke said: to ensure their liberties, their equality in the eyes of justice, their opportunity to live with decency. What were its origins? The tradition of English rights, the statutes conceded by the kings, the arrangement established between sovereign and parliament after 1688. In the government of the nation, the people participated through their representatives-not delegates, but representatives, elected from the ancient corporate bodies of the nation, rather than from an amorphous mass of subjects. What constituted the people? In Burke’s opinion, the public consisted of some four hundred thousand free men, possessed of leisure or property or membership in a responsible body which enabled them to apprehend the elements of politics. (Burke granted that the extent of the suffrage was a question to be determined by prudence and expedience, varying with the character of the age.) The country gentlemen, the farmers, the professional classes, the merchants, the manufacturers, the university graduates, in some constituencies the shopkeepers and prosperous artisans, the forty-shilling freeholders: men of these orders had the franchise. It was a proper balancing and checking of the several classes competent to exercise political influence-the crown, the peerage, the squirearchy, the middle classes, the old towns and the universities of the realm. Within one or another of these categories, the real interest of every person in England was comprehended. In good government, the object of voting is not to enable every man to express his ego, but to represent his interest, whether or not he casts his vote personally and directly. |

Selected texts

Edmund Burke. Reflections on The Revolution in France and on the Proceedings in Certain Societies in London Relative to that Event in a Letter Intended to have been sent to a Gentleman in Paris.

(…)

The ceremony of cashiering kings, of which these gentlemen talk so much at their ease, can rarely, if ever, be performed without force. It then becomes a case of war, and not of constitution. Laws are com manded to hold their tongues amongst arms, and tribunals fall to the ground with the peace they are no longer able to uphold. The Revolution of 1688 was obtained by a just war, in the only case in which any war, and much more a civil war, can be just. Justa bella quibus necessaria. The question of dethroning or, if these gentlemen like the phrase better, “cashiering kings” will always be, as it has always been, an extraordinary question of state, and wholly out of the law—a question (like all other questions of state) of dispositions and of means and of probable consequences rather than of positive rights. As it was not made for common abuses, so it is not to be agitated by common minds. The speculative line of demarcation where obedience ought to end and resistance must begin is faint, obscure, and not easily definable. It is not a single act, or a single event, which determines it. Governments must be abused and deranged, indeed, before it can be thought of; and the prospect of the future must be as bad as the experience of the past. When things are in that lamentable condition, the nature of the disease is to indicate the remedy to those whom nature has qualified to administer in extremities this critical, ambiguous, bitter potion to a distempered state. Times and occasions and provocations will teach their own lessons. The wise will determine from the gravity of the case; the irritable, from sensibility to oppression; the high-minded, from disdain and indignation at abusive power in unworthy hands; the brave and bold, from the love of honor able danger in a generous cause; but, with or without right, a revolution will be the very last resource of the thinking and the good.

The third head of right, asserted by the pulpit of the Old Jewry, namely, the “right to form a government for ourselves,” has, at least, as little countenance from anything done at the Revolution, either in prece dent or principle, as the two first of their claims. The Revolution was made to preserve our ancient, indisputable laws and liberties and that ancient constitution of government which is our only security for law and liberty. If you are desirous of knowing the spirit of our constitution and the policy which predominated in that great period which has secured it to this hour, pray look for both in our histories, in our records, in our acts of parliament, and journals of parliament, and not in the

sermons of the Old Jewry and the after-dinner toasts of the Revolution Society. In the former you will find other ideas and another language.

Such a claim is as ill-suited to our temper and wishes as it is unsupported by any appearance of authority. The very idea of the fabrication of a new government is enough to fill us with disgust and horror. We wished at the period of the Revolution, and do now wish, to derive all we possess as an inheritance from our forefathers. Upon that body and stock of inheritance we have taken care not to inoculate any scion alien to the nature of the original plant. All the reformations we have hitherto made have proceeded upon the principle of reverence to antiquity; and I hope, nay, I am persuaded, that all those which possibly may be made hereafter will be carefully formed upon analogical recedent, authority, and example.

(…)

You will observe that from Magna Charta to the Declaration of Right it has been the uniform policy of our constitution to claim and assert our liberties as an entailed inheritance derived to us from our forefathers, and to be transmitted to our posterity—as an estate specially belonging to the people of this kingdom, without any reference whatever to any other more general or prior right. By this means our constitution preserves a unity in so great a diversity of its parts. We have an inheritable crown, an inheritable peerage, and a House of Commons and a people inheriting privileges, franchises, and liberties from along line of ancestors.

This policy appears to me to be the result of profound reflection, or rather the happy effect of following nature, which is wisdom without reflection, and above it. A spirit of innovation is generally the result of a selfish temper and confined views. People will not look forward to posterity, who never look backward to their ancestors. Besides, the people of England well know that the idea of inheritance furnishes a sure principle of conservation and a sure principle of transmission, without at all excluding a principle of improvement. It leaves acquisition free, but it secures what it acquires.

(…)

Far am I from denying in theory, full as far is my heart from with holding in practice (if I were of power to give or to withhold) the real rights of men. In denying their false claims of right, I do not mean to injure those which are real, and are such as their pretended rights would totally destroy. If civil society be made for the advantage of man, all the advantages for which it is made become his right. It is an institution of beneficence; and law itself is only beneficence acting by a rule. Men have a right to live by that rule; they have a right to do justice, as be tween their fellows, whether their fellows are in public function or in ordinary occupation. They have a right to the fruits of their industry and to the means of making their industry fruitful. They have a right to the acquisitions of their parents, to the nourishment and improvement of their offspring, to instruction in life, and to consolation in death. What ever each man can separately do, without trespassing upon others, he has a right to do for himself; and he has a right to a fair portion of all which society, with all its combinations of skill and force, can do in his favor. In this partnership all men have equal rights, but not to equal things. He that has but five shillings in the partnership has as good a right to it as he that has five hundred pounds has to his larger propor tion. But he has not a right to an equal dividend in the product of the joint stock; and as to the share of power, authority, and direction which each individual ought to have in the management of the state, that I must deny to be amongst the direct original rights of man in civil society; for I have in my contemplation the civil social man, and no other. It is a thing to be settled by convention.

(…)

The science of constructing a commonwealth, or renovating it, or reforming it, is, like every other experimental science, not to be taught a priori. Nor is it a short experience that can instruct us in that practical science, because the real effects of moral causes are not always immediate; but that which in the first instance is prejudicial may be excellent in its remoter operation, and its excellence may arise even from the ileffects it produces in the beginning. The reverse also happens: and very plausible schemes, with very pleasing commencements, have often shameful and lamentable conclusions. In states there are often some obscure and almost latent causes, things which appear at first view of little moment, on which a very great part of its prosperity or adversity may most essentially depend. The science of government being therefore so practical in itself and intended for such practical purposes—a matter which requires experience, and even more experience than any person can gain in his whole life, however sagacious and observing he may be—it is with infinite caution that any man ought to venture upon pulling down an edifice which has answered in any tolerable degree for ages the common purposes of society, or on building it up again without having models and patterns of approved utility before his eyes.

(…)

You see, Sir, that in this enlightened age I am bold enough to confess that we are generally men of untaught feelings, that, instead of casting away all our old prejudices, we cherish them to a very consider able degree, and, to take more shame to ourselves, we cherish them because they are prejudices; and the longer they have lasted and the more generally they have prevailed, the more we cherish them. We are afraid to put men to live and trade each on his own private stock of reason, because we suspect that this stock in each man is small, and that the individuals would do better to avail themselves of the general bank and capital of nations and of ages. Many of our men of speculation, instead of exploding general prejudices, employ their sagacity to discover the latent wisdom which prevails in them. If they find what they seek, and they seldom fail, they think it more wise to continue the prejudice, with the reason involved, than to cast away the coat of prejudice and to leave nothing but the naked reason; because prejudice, with its reason, has a motive to give action to that reason, and an affection which will give it permanence. Prejudice is of ready application in the emergency; it previously engages the mind in a steady course of wisdom and virtue and does not leave the man hesitating in the moment of decision skeptical, puzzled, and unresolved. Prejudice renders a man’s virtue his habit, and not a series of unconnected acts. Through just prejudice, his duty becomes a part of his nature.

(…)

| A modern revolution aligned with Burke’s ideas: The Velvet Revolution in Czechoslovakia (1989). The Velvet Revolution was a non-violent protest movement that unfolded in Czechoslovakia from November 17 to December 29, 1989, ultimately ending over 40 years of communist rule and ushering in a peaceful transition to democracy. It began with a student demonstration in Prague commemorating the 50th anniversary of the Nazi murder of student Jan Opletal, which was brutally suppressed by riot police, sparking widespread outrage and mass protests across the country, including general strikes and negotiations led by dissident groups like Civic Forum under Václav Havel. The revolution’s name reflects its bloodless nature, achieved through civil resistance rather than armed conflict, culminating in the resignation of the communist leadership, free elections, and Havel’s election as president, marking a pivotal moment in the collapse of Eastern European communism. It preserved key institutions (like the legal system and economy) during the shift, built on pre-existing cultural and dissident traditions, and avoided the terror or radical restructuring Burke warned against, allowing for evolutionary reform toward freedom. |

Questions for reflection

1. How does Burke’s critique of the French Revolution’s attempt to rewrite society “on a blank sheet of paper” warn against the dangers of radical ideological overhauls in contemporary politics, such as rapid implementations of socialist or libertarian reforms?

2. How does Burke’s concept of “prejudice” as a positive force in society challenge modern views on bias and rationality in political decision-making?

3. How does the Burkean defense that “illusions and prejudices are socially necessary“—arguing that it is better to “trust the latent wisdom of prejudice” than to “set men to live and trade each with his own private stock of reason“—apply to debates about expertise versus folk knowledge?

4. In what ways might Burke’s warning about the dangers of abstract ideals apply to contemporary ideological movements, such as extreme environmentalism or identity politics?

5. Burke emphasized society as a partnership between past, present, and future generations—how does this perspective inform current debates on national debt and intergenerational equity?

6. Burke argued that rights must come with duties—how does this idea resonate with ongoing discussions about universal basic income or social welfare programs?

7. How does Burke’s defense of tradition and historical precedent contrast with contemporary pushes for constitutional reforms or the rewriting of historical narratives?

8. How does Burke’s critique of rationalism as “barbaric“—where revolutionaries adopted philosophy that ignored established traditions—inform analyses of contemporary movements that reject traditional cultural or religious institutions?

9. Considering Burke’s prediction of tyranny following radical change, how might this apply to analyzing the outcomes of recent revolutions or uprisings in countries like Venezuela or Syria?

10. Burke valued practical wisdom over theoretical speculation—how could this principle guide policymakers in addressing complex global issues like climate change or AI regulation today?

11. How does the Burkean standard of statesmanship—”a disposition to preserve and an ability to improve, taken together“—relate to contemporary approaches to institutional reform and social change?

12. What are the characteristics of a revolution that would have Burke’s support?

Leave a comment