Introduction

Barry Morris Goldwater (January 2, 1909 – May 29, 1998) was an American politician, widely regarded as the “father of modern conservatism” in the United States. He served in the U.S. Senate as a Republican from 1953 to 1965 and again from 1969 to 1987.

Figure 39. Barry Morris Goldwater.

Source. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Senator_Goldwater_1960.jpg

His 1960 book, The Conscience of a Conservative (ghostwritten by L. Brent Bozell Jr.), became a manifesto for limited government, individual liberty, and anti-communism, selling millions of copies and galvanizing the conservative movement.

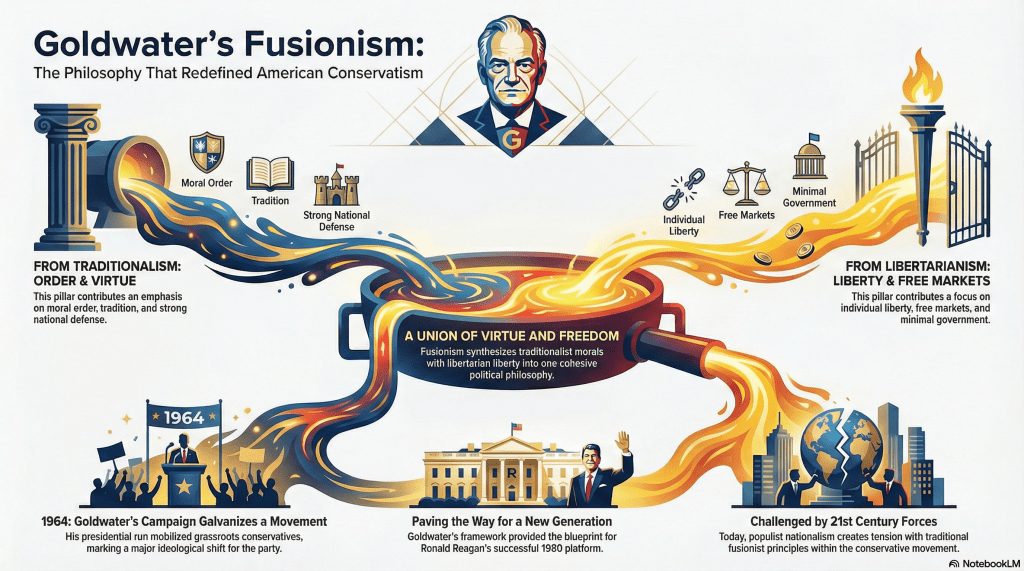

Goldwater’s Fusionism

Fusionism, as associated with Barry Goldwater, refers to a political philosophy that synthesizes traditional conservatism’s emphasis on moral order, tradition, and national defense with libertarianism’s focus on individual liberty, free markets, and minimal government intervention.

The term was coined by Frank Meyer, a key intellectual at National Review, who argued that true conservatism must fuse virtue (from traditionalists) with freedom (from libertarians) into a cohesive worldview, viewing it as an “organic” philosophy rooted in Western history rather than a mere tactical alliance.

Goldwater embodied this in practice as the “first political apostle” of fusionism, promoting limited government at home while advocating a strong anti-communist stance abroad.

In The Conscience of a Conservative, Goldwater articulated fusionism by calling for reduced federal power (e.g., opposing welfare expansion and labor unions’ influence), robust civil liberties, and a moral framework grounded in Judeo-Christian values, all while rejecting authoritarianism.

This approach aimed to reconcile tensions between social order and personal freedom, positing that individual liberty thrives within a traditional moral structure.

Critics sometimes viewed it as ideologically rigid, but proponents saw it as a principled response to expanding state power.

Historical Context

Goldwater’s fusionism emerged in the post-World War II era, amidst the ideological battles of the Cold War and the liberal (I mean, social-democratic. Americans call social democrats liberals, which causes quite a bit of confusion) dominance of the New Deal under Franklin D. Roosevelt and his successors.

The 1950s saw a fragmented conservative movement: traditionalists (emphasizing cultural heritage and anti-communism) clashed with libertarians (prioritizing economic freedom and isolationism), while both opposed the “Liberal Establishment” of big government and welfare statism.

Meyer and National Review (founded in 1955 by William F. Buckley Jr.) sought to unify these strands against communism abroad and socialism at home.

Goldwater’s 1964 presidential campaign tested fusionism politically, rallying grassroots conservatives disillusioned with moderate Republicans like Dwight D. Eisenhower.

His nomination marked a shift from “Modern Republicanism” toward a more ideological conservatism.

This era also overlapped with civil rights struggles; Goldwater’s vote against the 1964 Civil Rights Act (on federalism grounds) alienated moderates but appealed to states’ rights advocates.

Fusionism thus provided a framework for conservatives to challenge the post-war liberal consensus, laying groundwork for future victories.

Connection to the Circular Diagram of Political Mentalities

Goldwater’s fusionism directly connects to the Circular Diagram of Western Political Mentalities by bridging Classical Liberals (emphasizing individual autonomy, free markets, and limited government, akin to libertarianism; examples include Friedrich Hayek and Ron Paul) and Moderate Conservatives (valuing tradition, social stability, and gradual change; examples include Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher).

These two groups are adjacent in the circle, sharing commitments to free markets, democratic elections, and moderate government, which aligns with fusionism’s synthesis of liberty and order.

Goldwater opposed Radical Statists (e.g., fascist or communist authoritarianism) and Radical Leftists (revolutionary anti-capitalism), positioning him firmly in the classic-liberal conservative arc.

| Goldwater’s Fusionism as a Response to Hayek’s Critique of Conservatism Friedrich August von Hayek (1899-1992) was an Austrian economist. Although sometimes described as a conservative, Hayek himself felt uncomfortable with that label. In his book, The Constitution of Liberty, he wrote an entire chapter explaining why he was not a conservative (Why I Am Not a Conservative). While not a point-by-point rebuttal written in direct response, Goldwater’s fusionism functioned as a constructive response to Hayek’s critique, synthesizing the strengths of both sides, fostering a viable American conservatism that Hayek’s essay inadvertently challenged the movement to develop. Below are some excerpts from Hayek’s Why I Am Not a Conservative. “Let me now state what seems to me the decisive objection to any conservatism which deserves to be called such. It is that by its very nature it cannot offer an alternative to the direction in which we are moving. It may succeed by its resistance to current tendencies in slowing down undesirable developments, but, since it does not indicate another direction, it cannot prevent their continuance. It has, for this reason, invariably been the fate of conservatism to be dragged along a path not of its own choosing. The tug of war between conservatives and progressives can only affect the speed, not the direction, of contemporary developments. But, though there is need for a “brake on the vehicle of progress,” I personally cannot be content with simply helping to apply the brake. (…) (…) When I say that the conservative lacks principles, I do not mean to suggest that he lacks moral conviction. The typical conservative is indeed usually a man of very strong moral convictions. What I mean is that he has no political principles which enable him to work with people whose moral values differ from his own for a political order in which both can obey their convictions. It is the recognition of such principles that permits the coexistence of different sets of values that makes it possible to build a peaceful society with a minimum of force. The acceptance of such principles means that we agree to tolerate much that we dislike. There are many values of the conservative which appeal to me more than those of the socialists; yet for a liberal the importance he personally attaches to specific goals is no sufficient justification for forcing others to serve them.(…)To live and work successfully with others requires more than faithfulness to one’s concrete aims. It requires an intellectual commitment to a type of order in which, even on issues which to one are fundamental, others are allowed to pursue different ends. (…) That the conservative opposition to too much government control is not a matter of principle but is concerned with the particular aims of government is clearly shown in the economic sphere. Conservatives usually oppose collectivist and directivist measures in the industrial field, and here the liberal will often find allies in them. But at the same time conservatives are usually protectionists and have frequently supported socialist measures in agriculture. Indeed, though the restrictions which exist today in industry and commerce are mainly the result of socialist views, the equally important restrictions in agriculture were usually introduced by conservatives at an even earlier date. And in their efforts to discredit free enterprise many conservative leaders have vied with the socialists. I have already referred to the differences between conservatism and liberalism in the purely intellectual field, but I must return to them because the characteristic conservative attitude here not only is a serious weakness of conservatism but tends to harm any cause which allies itself with it. Conservatives feel instinctively that it is new ideas more than anything else that cause change. But, from its point of view rightly, conservatism fears new ideas because it has no distinctive principles of its own to oppose to them; and, by its distrust of theory and its lack of imagination concerning anything except that which experience has already proved, it deprives itself of the weapons needed in the struggle of ideas. (…)“ |

Modern Relevance

Goldwater’s fusionism remains influential in contemporary politics, shaping the Republican Party’s libertarian-conservative coalition and informing debates over government size, foreign policy, and cultural issues.

It paved the way for Ronald Reagan’s 1980 victory, blending free-market economics with social conservatism, and echoes in figures like Ron Paul and Rand Paul, who emphasize anti-interventionism and civil liberties.

In the Trump era, fusionism faces tensions: originally a Democrat with traits of populist nationalism (closer to Authoritarian Conservatism in the circular model), he challenges the traditional principles of fusionism, leading to internal divisions between “national conservatives” and factions inclined towards libertarianism.

| A New Fusionism? A 2024 Unpopular Front Substack post, titled “The New Fusionism,” examines the evolving conservative coalition under Trump’s influence, proposing a “neo-fusionism” that blends MAGA-style national populism with paleolibertarianism. It argues that traditional fusionism, which combined libertarian economics with social conservatism, has been disrupted by Trump’s populist nationalism, emphasizing protectionism, restricted immigration, and a strong executive. This new synthesis incorporates paleolibertarian anti-state rhetoric (e.g., against the “Deep State”) but contradicts it with demands for state intervention in trade and immigration. The post highlights tensions between working-class MAGA supporters and libertarians, noting that this uneasy alliance creates ideological inconsistencies, such as advocating for both a strong state and its dismantling. It contrasts this with the declining influence of traditional fusionism, driven by figures like William F. Buckley, and suggests that neo-fusionism’s contradictions may limit its coherence compared to the original fusionist model. (Source: https://www.unpopularfront.news/p/trumps-neo-fusionism) |

It also informs ongoing discussions on fiscal policy, with fusionism’s anti-welfare stance influencing resistance to expansive social programs, while its anti-authoritarian ethos critiques modern surveillance states and identity politics.

Globally, fusionist ideas appear in movements advocating market reforms alongside cultural preservation, reminding conservatives of the need for principled unity amid polarization.

Key Quotes from The Conscience of a Conservative (1960)

“The legitimate functions of government are actually conducive to freedom. Maintaining internal order, keeping foreign foes at bay, administering justice, removing obstacles to the free interchange of goods—the exercise of these powers makes it possible for men to follow their chosen pursuits with maximum freedom. But note that the very instrument by which these desirable ends are achieved can be the instrument for achieving undesirable ends—that government can, instead of extending freedom, restrict freedom.” (This quote illustrates fusionism by linking limited government to both liberty and moral/social order.)

“Throughout history, government has proved to be the chief instrument for thwarting man’s liberty. Government represents power in the hands of some men to control and regulate the lives of other men. And power, as Lord Acton said, corrupts men. ‘Absolute power,’ he added, ‘corrupts absolutely.’” (Emphasizing libertarian distrust of state power while invoking traditional moral warnings against corruption)

“The material and spiritual sides of man are intertwined; that it is impossible for the State to assume responsibility for one without intruding on the essential nature of the other; that if we take from a man the personal responsibility for caring for his material needs, we take from him also the will and the opportunity to be free.” (Fusion of economic liberty with spiritual/moral individualism.)

“Surely the first obligation of a political thinker is to understand the nature of man. The Conservative does not claim special powers of perception on this point, but he does claim a familiarity with the accumulated wisdom and experience of history, and he is not too proud to learn from the great minds of the past. The first thing he has learned about man is that each member of the species is a unique creature. Man’s most sacred possession is his individual soul—which has an immortal side, but also a mortal one. The mortal side establishes his absolute differentness from every other human being. Only a philosophy that takes into account the essential differences between men, and, accordingly, makes provision for developing the different potentialities of each man can claim to be in accord with Nature. We have heard much in our time about ‘the common man.’ It is a concept that pays little attention to the history of a nation that grew great through the initiative and ambition of uncommon men. The Conservative knows that to regard man as part of an undifferentiated mass is to consign him to ultimate slavery.” (Highlighting traditionalist views on human nature and uniqueness, tied to libertarian rejection of collectivism.)

Questions for Reflection

1. How does Barry Goldwater’s fusionism, blending traditional moral order with libertarian emphasis on individual freedom, reflect on the internal tensions within the modern Republican Party, particularly between social conservatives and fiscal libertarians?

2. How might Goldwater’s fusionism help resolve current tensions between libertarian emphasis on personal freedom and conservative focus on traditional values in today’s political parties?

3. In the context of the Circular Diagram, could fusionism facilitate alliances between Classical Liberals and Moderate Conservatives to counter rising Radical Statism or Radical Leftism in global politics?

4. How has the evolution of fusionism influenced your own political views, particularly regarding government intervention in economic vs. social issues?

5. Considering modern relevance, does fusionism still provide a viable framework for conservatism, or has it been eclipsed by populist or nationalist mentalities?

6. Reflect on Goldwater’s warning that government power can corrupt and restrict freedom, as quoted in The Conscience of a Conservative—in what ways might this apply to contemporary concerns over executive overreach in areas like surveillance or emergency powers during crises?

7. Discuss the implications of Goldwater’s view that man’s individual soul and uniqueness must be protected from collectivist tendencies; how could this critique inform current debates on identity politics and group-based policies in diverse societies?

8. In what ways does Goldwater’s anti-welfare stance, emphasizing personal responsibility over state intervention, challenge modern progressive policies like universal basic income or expanded social safety nets in economies facing inequality?

9. In the case of Brazil, how can Goldwater’s fusionism help a small political party originally formed by libertarians, such as the Partido Novo, to make alliances with more conservative (especially traditionalists) and more numerous groups?

Leave a comment