Contextualization

Michael Oakeshott (1901–1990) was a British philosopher whose work spanned political theory, philosophy of history, and education.

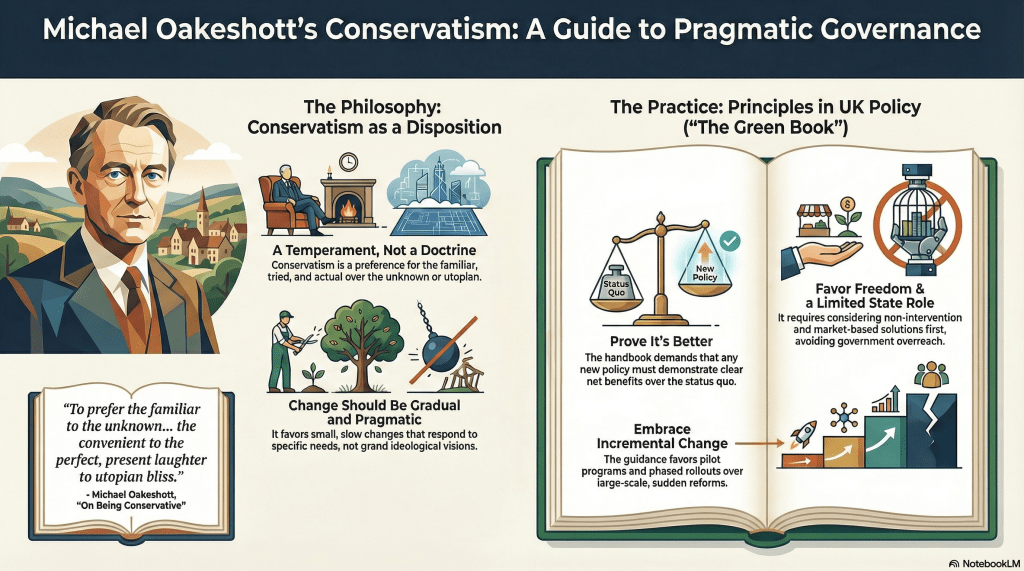

Figure 36: Michael Oakeshott.

Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Michael_Oakeshott.jpg

His ideas on conservatism emerged in the mid-20th century, amid post-World War II debates on ideology, rationalism, and governance. Key works include his 1956 essay “On Being Conservative,” where he articulated conservatism not as a fixed doctrine but as a practical disposition suited to navigating change in established societies.

Oakeshott’s thought critiqued both utopian rationalism (e.g., in socialism or liberalism’s grand plans) and rigid traditionalism, positioning him as a skeptic of ideological extremes in an era of ideological conflicts like the Cold War.

Main Ideas About Conservatism

Oakeshott viewed conservatism primarily as a “disposition” or temperament, rather than a rigid ideology or set of principles.

In his famous formulation, to be conservative is “to prefer the familiar to the unknown, to prefer the tried to the untried, fact to mystery, the actual to the possible, the limited to the unbounded, the near to the distant, the sufficient to the superabundant, the convenient to the perfect, present laughter to utopian bliss.”

This emphasizes enjoying and preserving what is present and available, rather than pursuing abstract ideals or radical transformations. He argued that humans inherit a world of practices, institutions, and traditions that should be approached with humility and skepticism toward “rationalist” schemes that seek to redesign society from scratch.

Central to his ideas is the notion that change should be gradual and pragmatic, responding to specific circumstances rather than driven by ideology. Governing, for Oakeshott, is a “specific and limited activity” focused on maintaining order and enabling individual pursuits, not imposing comprehensive visions.

He distinguished this from “enterprise” politics, where the state pursues ambitious goals like equality or national glory. Conservatism thus favors stability, continuity, and the rule of law as evolved practices, while being wary of innovation for its own sake.

Overall, his conservatism is non-dogmatic, rooted in experience and tradition, and adaptable to liberal democratic contexts.

How His Ideas Fit into the Circular Diagram of Political Mindsets

Oakeshott’s ideas align most closely with the Moderate Conservatives group, which values tradition, social stability, gradual change, and the defense of established institutions while often incorporating liberal economic policies and moderate government.

His emphasis on preferring the familiar, pragmatic governance, and skepticism of radical innovation mirrors this group’s focus on continuity and balance, distinguishing it from the more rigid hierarchy and nationalism of Authoritarian Conservatives.

However, Oakeshott’s disposition also overlaps with adjacent Classical Liberals, sharing commitments to limited government, individual pursuits, and civil liberties—evident in his support for free markets and rule of law as evolved practices rather than ideological impositions.

In the diagram’s circular logic, this positions him away from opposites like Radical Statists (who favor state supremacy and coercion, antithetical to his limited governance) or Radical Leftists (who pursue revolutionary equality, clashing with his anti-utopian pragmatism). His thought exemplifies the model’s fluid transitions, blending conservative temperament with liberal elements in response to context, rather than fitting neatly into one static category.

Key quotes from On being Conservative

“My theme is not a creed or a doctrine, but a disposition. To be conservative is to be disposed to think and behave in certain manners; it is to prefer certain kinds of conduct and certain conditions of human circumstances to others; it is to be disposed to make certain kinds of choices. And my design here is to construe this disposition as it appears in contemporary character, rather than to transpose it into the idiom of general principles.”

“To be conservative, then, is to prefer the familiar to the unknown, to prefer the tried to the untried, fact to mystery, the actual to the possible, the limited to the unbounded, the near to the distant, the sufficient to the superabundant, the convenient to the perfect, present laughter to utopian bliss.”

“Consequently, he will find small and slow changes more tolerable than large and sudden; and he will value highly every appearance of continuity.”

“Thus, whenever there is innovation there is the certainty that the change will be greater than was intended, that there will be loss as well as gain and that the loss and the gain will not be equally distributed among the people affected; there is the chance that the benefits derived will be greater than those which were designed; and there is the risk that they will be off-set by changes for the worse.”

“(…), what makes a conservative disposition in politics intelligible is nothing to do with natural law or a providential order, nothing to do with morals or religion; it is the observation of our current manner of living combined with the belief (which from our point of view need be regarded as no more than an hypothesis) that governing is a specific and limited activity, namely the provision and custody of general rules of conduct, which are understood, not as plans for imposing substantive activities, but as instruments enabling people to pursue the activities of their own choice with the minimum frustration, and therefore something which it is appropriate to be conservative about.”

Relevance of His Ideas Today

Oakeshott’s ideas remain highly relevant in an era of political polarization, populism, and ideological extremism, offering a counterpoint to both left-wing utopianism and right-wing authoritarianism. In a world grappling with rapid technological change, global crises, and cultural upheavals, his advocacy for enjoying the present and preferring gradual, experience-based reforms challenges the “rationalist” impulses behind sweeping policies.

For instance, amid debates on issues like social media regulation or economic inequality, his limited view of government as a maintainer of order, not an engineer of society, critiques overreach in both welfare states and surveillance regimes.

His ideas also resonate in educational and cultural discussions, advocating for liberal learning as a conversation with traditions, countering polarized “culture wars.” In the context of the circular diagram, his moderate stance highlights the risks of sliding toward adjacent extremes, urging a balanced mentality that could foster dialogue in divided democracies. Ultimately, in an age of uncertainty, Oakeshott’s call to delight in the “present laughter” over utopian dreams promotes resilience and humility, making his philosophy a timely antidote to radicalism.

| Convergence between the UK Policy Making Handbook and Oakeshott’s ideas The Green Book, as HM Treasury‘s guidance on appraising and evaluating central government policies, programs, and projects (updated in 2022 with references to the 2020 version), promotes a structured, evidence-based approach to decision-making that emphasizes caution, proportionality, and demonstrated value. While it is a practical toolkit rather than a philosophical treatise, several elements converge with Michael Oakeshott’s conservative disposition. Below, some examples grouped by theme, drawing on specific sections of The Green Book, and explain the alignment with Oakeshott’s ideas 1. Duty to Demonstrate Net Benefits Over the Status Quo The Green Book mandates rigorous cost-benefit analysis (CBA) to ensure any policy change delivers net social value, placing the onus on proposers to quantify benefits outweighing costs compared to doing nothing or minimal action. This mirrors Oakeshott’s view that “the onus of proof, to show that the proposed change may be expected to be on the whole beneficial, rests with the would-be innovator,” rejecting changes without reasonable certainty of gain. Example: It requires calculating Net Present Social Value (NPSV) as “the present value of benefits less the present value of costs,” using tools like Benefit Cost Ratios (BCR) to rank options, adjusted for inflation, discounting, and risks. If NPSV is not positive or superior to alternatives, the proposal is unlikely to proceed. Convergence: This enforces Oakeshott’s pragmatic skepticism toward innovation, preferring the “sufficient to the superabundant” by demanding evidence-based proof that change avoids “certain loss” without commensurate gain, aligning with his disposition to preserve the familiar unless demonstrably improved. 2. Preference for Alternatives That Increase Freedom or Reduce State Role The guidance stresses evaluating non-interventionist options, including “Business As Usual (BAU)” or “do-minimum,” and considers deregulatory or market-based alternatives, which echoes Oakeshott’s limited view of government as a custodian of rules enabling individual pursuits, rather than expansive enterprise. Example: Shortlists must include BAU (the status quo as counterfactual), a “do-minimum” option meeting only core needs, and alternatives like regulation changes, nudges, grants, or Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs) to transfer risks and reduce direct state involvement. It justifies intervention only for market failures (e.g., public goods, externalities), otherwise favoring options that optimize social value with minimal public sector overreach. Convergence: This fits Oakeshott’s preference for the “limited to the unbounded,” where policy should consider shrinking the state’s role to enhance personal freedoms, avoiding ideological impositions and respecting evolved practices over grand designs. 3. Preference for Incremental, Specific, and Fragmented Changes The Green Book favors targeted, phased approaches over comprehensive or abstract reforms, advocating pilots and staged implementation to address specific issues, which aligns with Oakeshott’s advocacy for “small and slow changes” that respond to “some specific defect” rather than visions of “generally improved” conditions. Example: It promotes “piloting and a ‘phased learning development roll out process,’ with adaptation and building on what works between each phase,” using real options analysis for uncertainty and breaking projects into stages with review points to allow adjustments or halting. Policies should focus on SMART (Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Realistic, Time-limited) objectives, avoiding predetermined holistic solutions. Convergence: This reflects Oakeshott’s disposition to value “the convenient to the perfect,” prioritizing delimited fixes over utopian abstractions, ensuring changes maintain continuity and are grounded in evidence rather than ideological ambition. 4. Consideration of Timing, Implementation Risks, and Unintended Consequences Emphasizing slow pacing and risk management, The Green Book requires accounting for uncertainties, optimism bias, and unintended effects, converging with Oakeshott’s call for a “slow rather than a rapid pace” and pauses to “observe current consequences and make appropriate adjustments,” recognizing the unpredictability of human affairs. Example: It addresses uncertainty through sensitivity analysis, scenario planning, Monte Carlo methods, and optimism bias adjustments (defined as “the proven tendency for appraisers to be optimistically biased about key project parameters“). Unintended consequences, such as behavioral changes or collateral effects, must be considered via systems analysis and post-implementation monitoring/evaluation to identify “unexpected outcomes.“ Convergence: This embodies Oakeshott’s caution against the “grief of loss” from uncharted innovations, favoring humility in the face of complexity and a temperament that delights in the present while mitigating risks through deliberate timing and adaptive management. Overall, these convergences highlight how The Green Book operationalizes a conservative-like prudence in public policymaking—evidence-driven, restrained, and respectful of the status quo—without explicitly invoking philosophy. It counters rationalist overreach by embedding Oakeshottian themes like burden of proof and incrementalism into bureaucratic processes, making it a practical embodiment of his ideas in modern governance. (https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/the-green-book-appraisal-and-evaluation-in-central-government/the-green-book-2020) |

Questions for reflection

1. Is Oakeshott’s conservatism just a handbrake? A restriction on sudden changes in society, without providing a direction to follow?

2. Consider a citizen of the former East Germany who lived before the fall of the Berlin Wall. As he experienced its fall, how would he express himself about this change?

3. Are the rules in the Green Book sufficient to guarantee a free society? Or to prevent the reckless expansion of the state?

4. How does Oakeshott’s critique of “rationalism in politics”—where politicians approach governance “like engineers confronted with problems to be solved by design”—apply to contemporary debates about technological solutionism and data-driven governance?

5. How does Oakeshott’s distinction between practical knowledge (acquired through experience) and theoretical/propositional knowledge inform discussions about the role of experts versus elected officials in decision-making?

6. How does Oakeshott’s differentiation between the state as “civil association” (societas)—governed by general rules of conduct—versus “business association” (universitas)—organized around substantive collective goals—explain contemporary political divisions?

7. What insights does the Oakeshottian metaphor that “political life is not architecture but horticulture: not the erection of a tower, but the tending of a garden” offer for contemporary approaches to institutional reform?

8. Discuss the implications of Oakeshott’s view that governing is a “specific and limited activity” focused on rules of conduct rather than substantive goals; how might this challenge contemporary progressive policies aiming for social equity through expansive state interventions?

9. In what ways does Oakeshott’s skepticism toward “rationalist” schemes, which impose abstract ideals, parallel criticisms of utopian elements in modern environmental agendas, like the push for net-zero emissions without considering incremental feasibility?

10. In what ways does Oakeshott’s rejection of both ideological extremism and rigid traditionalism resonate with efforts to combat political polarization on social media platforms today, where echo chambers amplify radical views?

Leave a comment