Introduction

Charles-Louis de Secondat, Baron de Montesquieu, was a French philosopher and jurist whose seminal work, The Spirit of the Laws (1748), reshaped political thought by emphasizing that laws must be adapted to the unique characteristics of a society—its people, culture, geography, and form of government. Writing during the Enlightenment, a period of intellectual effervescence that challenged absolute monarchies, Montesquieu advocated for a government structured to preserve liberty through the separation of powers and the adaptation of laws to specific contexts. In the circular diagram of political mindsets, Montesquieu is a pillar of the classical liberal perspective, championing individual liberty and balanced governance while opposing the unfettered authority of radical statists and conservative authoritarians. His ideas profoundly influenced modern constitutional design, notably the United States Constitution, and continue to resonate in debates about governance and liberty.

Montesquieu’s Core Ideas: The Spirit of the Laws

In The Spirit of the Laws, Montesquieu argues that effective governance requires laws that reflect the specific conditions of a society. He writes:

“They [laws] should be adapted in such a manner to the people for whom they are framed that it should be a great chance if those of one nation suit another” (The Spirit of the Laws, Book I, Chapter 3).

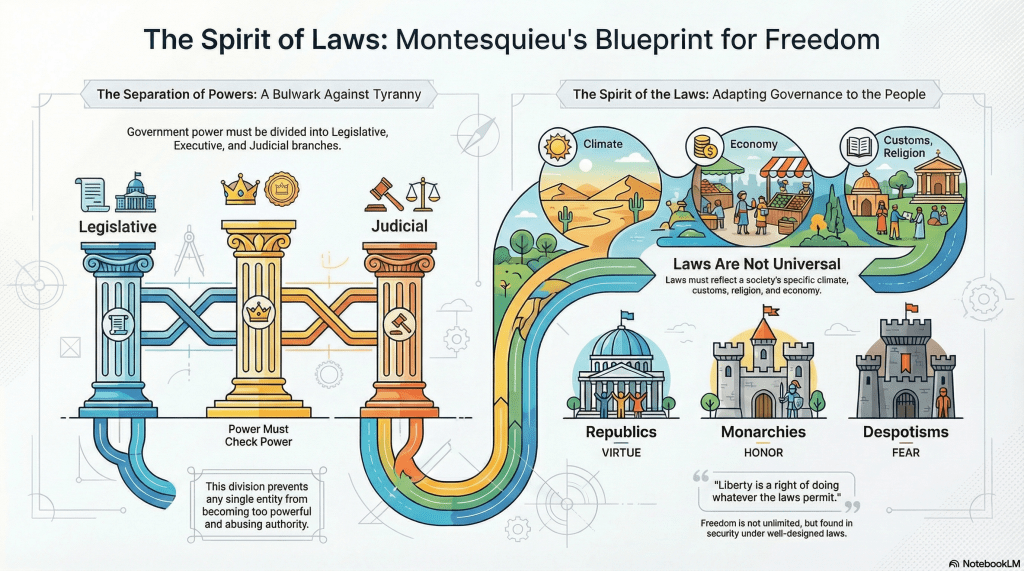

This principle reinforces Montesquieu’s belief that laws are not universal but must take into account a society’s climate, geography, religion, customs, and economic conditions. For example, he suggests that warmer climates may promote different social behaviors than temperate ones, influencing the types of laws needed. Similarly, he argues that the “spirit” or principle of each government—honor in monarchies, virtue in republics, fear in despotisms—shapes the laws that sustain it.

Figura 13. Charles-Louis de Secondat, Barão de Montesquieu

Author: Jacques-Antoine Dassier (1715-1759)

Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Montesquieu_1.png

Montesquieu’s most lasting contribution, however, is his doctrine of the separation of powers. He proposed that government functions be divided into three branches—legislative, executive, and judicial—to prevent any one branch from dominating and to safeguard liberty. He writes:

“When the legislative and executive powers are united in the same person, or in the same body of magistrates, there can be no liberty; …Again, there is no liberty, if the judiciary power be not separated from the legislative and executive” (The Spirit of the Laws, Book XI, Chapter 6).

This separation, combined with checks and balances, ensures that power remains diffuse, preventing tyranny. Montesquieu’s admiration for the English constitution, particularly after the Glorious Revolution, inspired this model, as he saw England’s balanced system as a bulwark against absolutism.

| Courts May Not Exceed Their Powers Justice Amy Coney BARRETT (1972) of the Supreme Court of the United States issued the following decision for the Court in a case involving President Trump, on Petition for Partial Stay No. 24A884 (Argued May 15, 2025—Decided June 27, 2025): “The United States has filed three emergency applications challenging the scope of a federal court’s authority to enjoin Government officials from enforcing an executive order. Traditionally, courts issued injunctions prohibiting executive officials from enforcing a challenged law or policy only against the plaintiffs in the lawsuit. The injunctions before us today reflect a more recent development: district courts asserting the power to prohibit enforcement of a law or policy against anyone. These injunctions—known as “universal injunctions”—likely exceed the equitable authority that Congress has granted to federal courts. We therefore grant the Government’s applications to partially stay the injunctions entered below. (…) Some say that the universal injunction “give[s] the Judiciary a powerful tool to check the Executive Branch.(…). But federal courts do not exercise general oversight of the Executive Branch; they resolve cases and controversies consistent with the authority Congress has given them. When a court concludes that the Executive Branch has acted unlawfully, the answer is not for the court to exceed its power, too.” Source https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/24pdf/24a884_8n59.pdf?ftag=MSF0951a18 |

Montesquieu’s Contextual Approach to Liberty

Unlike John Locke, who grounded liberty in universal natural rights, Montesquieu emphasized liberty as a practical result of well-designed institutions tailored to specific societies. He defined liberty as “the right to do whatever the laws permit” (The Spirit of the Laws, Book XI, Chapter 3), suggesting that liberty arises from security under just laws, not from unbridled individualism. This pragmatic approach distinguishes Montesquieu from classical liberalism, as he balanced individual liberty with the need for social order, recognizing that liberty depends on a nation’s cultural and historical context.

Montesquieu also classified governments into three types—republics, monarchies, and despotisms—each with distinct principles and risks. Republics are based on civic virtue but can degenerate into anarchy; monarchies rely on honor but risk corruption; Despotisms, driven by fear, inherently suppress freedom. His analysis warns against absolutism, advocating for moderate governance that respects local conditions and protects individual rights.

Other relevant ideas from Montesquieu

Among other lessons from Montesquieu, we highlight the following:

- When people come together in societies, they glimpse the possibility and act to exploit others (the emergence of factions), hence the need for the rights of nations and politics.

- Laws must be appropriate to the people and their circumstances, and to the nature and principles of each government.

- The creation and maintenance of a democratic republic (government of laws) requires that the people have a love for the republic, which must be built and maintained by the educational system.

- In a republic, freedom can only consist in the power to do what we should want and not be forced to do what we should not want. The political freedom of the individual is a tranquility of mind that arises from each person’s opinion of their own security.

- Freedom can only exist in moderate governments, where one power acts as a check on another.

- For freedom to exist, the three powers—executive, legislative, and judicial—must be separated.

- The judiciary, of the three, is the least dangerous because it is merely the mouth of the law (when it is, in fact, constituted as such, that is, when it possesses only the power to judge accordingly to the laws).

- For the judiciary to be perceived as just, judges must be of the same status as the accused (the right to be judged by their peers).

Relationship with the Circular Diagram

In the circular diagram of political mentalities, Montesquieu firmly occupies the classical liberal position, with his emphasis on liberty, limited government, and institutional balance. His ideas connect with adjacent groups and oppose others:

Democratic Leftists: Montesquieu’s focus on representative institutions and liberty aligns with democratic socialists, who value governance responsive to the people, though they disagree on economic intervention. His ideas about adapting laws to social conditions resonate with social democratic reforms that consider cultural and economic contexts, such as the Swedish welfare state.

Moderate Conservatives: Montesquieu’s respect for tradition and gradual change, as seen in his admiration for the evolution of the English constitution, aligns with moderate conservatives who advocate stable, incremental reforms. His pragmatic approach to governance unites liberal and conservative values, as seen in his influence on figures like Edmund Burke, who valued balanced institutions.

Opposition to Radical Statists and Authoritarian Conservatives: Montesquieu’s rejection of despotism and centralized power places him in direct opposition to radical statists, such as Mussolini’s fascist regime, and conservative authoritarians, such as Franco’s Spain, who prioritized control over liberty. His doctrine of the separation of powers explicitly opposes their concentration of authority.

Modern Relevance

Montesquieu’s ideas remain vital in contemporary debates about governance. His doctrine of separation of powers underpins modern democracies, ensuring the control of authority in systems like the United States and parliamentary democracies. His contextual approach to law is relevant in discussions of federalism, where policies must take regional differences into account, or in global governance, where universal laws often conflict with cultural realities.

| There is no judicial supremacy In a well-known speech, Stephen Miller (1985), political advisor and homeland security advisor to the Donald Trump administration, stated that there is no judicial supremacy. His understanding seems inspired by Thomas Jefferson, one of the founding fathers of the United States: “The 2d question whether the judges are invested with exclusive authority to decide on the constitutionality of a law, has been heretofore a subject of consideration with me in the exercise of official duties. certainly there is not a word in the constitution which has given that power to them more than to the Executive or Legislative branches. questions of property, of character and of crime being ascribed to the judges, through a definite course of legal proceeding, laws involving such questions belong of course to them; and as they decide on them ultimately & without appeal, they of course decide, for themselves, the constitutional validity of the law. on laws again prescribing executive action, & to be administered by that branch ultimately and without appeal, the Executive must decide for themselves also, whether, under the constitution, they are valid or not. so also as to laws governing the proceedings of the legislature, that body must judge for itself the constitutionality of the law, & equally without appeal or controul from it’s coordinate branches. and, in general, that branch which is to act ultimately, and without appeal, on any law, is the rightful expositor of the validity of the law, uncontrouled by the opinions of the other coordinate authorities. it may be said that contradictory decisions may arise in such case, and produce inconvenience. this is possible, and is a necessary failing in all human proceedings. yet the prudence of the public functionaries, and authority of public opinion will generally produce accomodation. such an instance of difference occurred between the judges of England (in the time of Ld Holt) and the House of Commons. but the prudence of those bodies prevented inconvenience from it. so in the cases of Duane and of William Smith of S. Carolina, whose characters of citizenship stood precisely on the same ground, the judges in a question of meum and tuum which came before them, decided that Duane was not a citizen; and in a question of membership the House of Representatives under the same words of the same provision2 adjudged William Smith to be a citizen. yet no inconvenience has ensued these contradictory decisions. this is what I believe myself to be sound. but there is another opinion entertained by some men of such judgment & information as to lessen my confidence in my own. that is, that the legislature alone is the exclusive expounder of the sense of the constitution in every part of it whatever. and they alledge in it’s support that this branch has authority, to impeach and punish a member of either of the others acting contrary to it’s declaration of the sense of the constitution. it may indeed be answered that an act may still be valid altho’ the party is punished for it, right or wrong. however this opinion which ascribes exclusive exposition to the legislature merits respect for it’s safety, there being in the body of the nation a controul over them, which, if expressed by rejection on the subsequent exercise of their elective franchise, enlists public opinion against their exposition, and encourages a judge or Executive on a future occasion3 to adhere to their former opinion. between these two doctrines, every one has a right to chuse; and I know of no third meriting any respect.“ (Source: https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/03-08-02-0427) |

Montesquieu’s principles guide those seeking governance that respects both individual liberty and social diversity, making his work a benchmark for classical liberalism.

Conclusion

Montesquieu’s The Spirit of the Laws offers a vision of governance in which laws are tailored to the unique characteristics of a people and their government, ensuring liberty through the separation of powers and contextual sensitivity. His ideas cement his place in the classical liberal mindset of the circle diagram, uniting democratic and conservative values while opposing authoritarianism. By advocating for balanced institutions and laws suited to specific societies, Montesquieu provided a framework that shaped modern democracies and continues to inform debates on liberty and governance. His legacy reminds us that liberty thrives not on universal mandates, but on systems carefully designed to reflect human diversity and protect individual rights.

Key Quote

“Liberty is the right to do whatever the laws permit, and laws should be so framed as not to allow too much power in the hands of any one person” (The Spirit of the Laws, Book XI, Chapter 3).

Selected Texts

Book I. Of Laws in General

1. Of the relation of laws to diferent beings

Laws, in their most general signification, are the necessary relations arising from the nature of things. In this sense all beings have their laws: the Deity. His laws, the material world its laws, the intelligences superior to man their laws, the beasts their laws, man his laws.

They who assert that a blind fatality produced the various effects we behold in this world talk very absurdly; for can anything be more unreasonable than to pretend that a blind fatality could be productive of intelligent beings?

There is, then, a prime reason; and laws are the relations subsisting between it and different beings, and the relations of these to one another.

God is related to the universe, as Creator and Preserver; the laws by which He created all things are those by which He preserves them. He acts according to these rules, because He knows them; He knows them, because He made them; and He made them, because they are in relation to His wisdom and power.

Since we observe that the world, though formed by the motion of matter, and void of understanding, subsists through so long a succession of ages, its motions must certainly be directed by invariable laws; and could we imagine another world, it must also have constant rules, or it would inevitably perish.

Thus the creation, which seems an arbitrary act, supposes laws as invariable as those of the fatality of the Atheists. It would be absurd to say that the Creator might govern the world without those rules, since without them it could not subsist.

(…)

2. Of The Laws of Nature

Antecedent to the above-mentioned laws are those of nature, so called, because they derive their force entirely from our frame and existence. In order to have a perfect knowledge of these laws, we must consider man before the establishment of society: the laws received in such a state would be those of nature.

The law which, impressing on our minds the idea of a Creator, inclines us towards Him, is the first in importance, though not in order, of natural laws. Man in a state of nature would have the faculty of knowing, before he had acquired any knowledge. Plain it is that his first ideas would not be of a speculative nature; he would think of the preservation of his being, before he would investigate its origin. Such a man would feel nothing in himself at first but impotency and weakness; his fears and apprehensions would be excessive; as appears from instances (were there any necessity of proving it) of savages found in forests, trembling at the motion of a leaf, and flying from every shadow.

In this state every man, instead of being sensible of his equality, would fancy himself inferior. There would therefore be no danger of their attacking one another; peace would be the first law of nature.

The natural impulse or desire which Hobbes attributes to mankind of subduing one another is far from being well founded. The idea of empire and dominion is so complex, and depends on so many other notions, that it could never be the first which occurred to the human understanding.

Hobbes inquires, “For what reason go men armed, and have locks and keys to fasten their doors, if they be not naturally in a state of war?” But is it not obvious that he attributes to mankind before the establishment of society what can happen but in consequence of this establishment, which furnishes them with motives for hostile attacks and self-defence?

Next to a sense of his weakness man would soon find that of his wants. Hence another law of nature would prompt him to seek for nourishment.

Fear, I have observed, would induce men to shun one another; but the marks of this fear being reciprocal, would soon engage them to associate. Besides, this association would quickly follow from. the very pleasure one animal feels at the approach of another of the same species. Again, the attraction arising from the difference of sexes would enhance this pleasure, and the natural inclination they have for each other would form a third law.

Beside the sense or instinct which man possesses in common with brutes, he has the advantage of acquired knowledge; and thence arises a second tie, which brutes have not. Mankind have therefore a new motive of uniting; and a fourth law of nature results from the desire of living in society.

3. Of Positive Laws

As soon as man enters into a state of society he loses the sense of his weakness; equality ceases, and then commences the state of war.

Each particular society begins to feel its strength, whence arises a state of war between different nations. The individuals likewise of each society become sensible of their force; hence the principal advantages of this society they endeavour to convert to their own emolument, which constitutes a state of war between individuals.

These two different kinds of states give rise to human laws. Considered as inhabitants of so great a planet, which necessarily contains a variety of nations, they have laws relating to their mutual intercourse, which is what we call the law of nations. As members of a society that must be properly supported, they have laws relating to the governors and the governed, and this we distinguish by the name of politic law. They have also another sort of law, as they stand in relation to each other; by which is understood the civil law.

The law of nations is naturally founded on this principle, that different nations ought in time of peace to do one another all the good they can, and in time of war as little injury as possible, without prejudicing their real interests.

The object of war is victory; that of victory is conquest; and that of conquest preservation. From this and the preceding principle all those rules are derived which constitute the law of nations.

(…)

Book 3. Of the Principles of the Three Kinds of Government

1. Difference Between Nature and Principle of Government

Having examined the laws in relation to the nature of each government, we must investigate those which relate to its principle.

There is this difference between the nature and principle of government,that the former is that by which it is constituted, the latter that by which it is made to act. One is its particular structure, and the other the human passions which set it in motion.

Now, laws ought no less to relate to the principle than to the nature of each government. We must, therefore, inquire into this principle, which shall be the subject of this third book.

2. Of the Principle of different Governments

I have already observed that it is the nature of a republican government that either the collective body of the people, or particular families, should be possessed of the supreme power; of a monarchy,that the prince should have this power, but in the execution of it should be directed by established laws; of a despotic government, that a single person should rule according to his own will and caprice.This enables me to discover their three principles; which are thence naturally derived. I shall begin with a republican government, and in particular with that of democracy.

3. Of the Principle of Democracy

There is no great share of probity necessary to support a monarchical or despotic government. The force of laws in one, and the prince’s arm in the other, are sufficient to direct and maintain the whole. But in a popular state, one spring more is necessary, namely, virtue.

What I have here advanced is confirmed by the unanimous testimony of historians, and is extremely agreeable to the nature of things. For it is clear that in a monarchy, where he who commands the execution of the laws generally thinks himself above them, there is less need of virtue than in a popular government, where the person entrusted with the execution of the laws is sensible of his being subject to their direction.

(…)

When virtue is banished, ambition invades the minds of those who are disposed to receive it, and avarice possesses the whole community. The objects of their desires are changed; what they were fond of before has become indifferent;they were free while under the restraint of laws, but they would fain now be free to act against law; and as each citizen is like a slave who has run away from his master, that which was a maxim of equity he calls rigour; that which was a rule of action he styles constraint; and to precaution he gives the name of fear. Frugality, and not the thirst of gain, now passes for avarice. Formerly the wealth of individuals constituted the public treasure; but now this has become the patrimony of private persons. The members of the commonwealth riot on the public spoils, and its strength is only the power of a few, and the licence of many.

(…)

Book XI. Of the Laws Which Establish Political Liberty, with Regard to the Constitution.

(…)

2. Different Significations of the Word Liberty

There is no word that admits of more various significations, and has made more varied impressions on the human mind, than that of liberty. Some have taken it as a means of deposing a person on whom they had conferred a tyrannical authority; others for the power of choosing a superior whom they are obliged to obey; others for the right of bearing arms, and of being thereby enabled to use violence; others, in fine, for the privilege of being governed by a native of their own country, or by their own laws. A certain nation for a long time thought liberty consisted in the privilege of wearing a long beard. Some have annexed this name to one form of government exclusive of others: those who had a republican taste applied it to this species of polity; those who liked a monarchical state gave it to monarchy. Thus they have all applied the name of liberty to the government most suitable to their own customs and inclinations: and as in republics the people have not so constant and so present a view of the causes of their misery, and as the magistrates seem to act only in conformity to the laws, hence liberty is generally said to reside in republics, and to be banished from monarchies. In fine, as in democracies the people seem to act almost as they please, this sort of government has been deemed the most free, and the power of the people has been confounded with their liberty.

3. In What Liberty Consists.

It is true that in democracies the people seem to act as they please; but political liberty does not consist in an unlimited freedom. In governments, that is, in societies directed by laws, liberty can consist only in the power of doing what we ought to will, and in not being constrained to do what we ought not to will.

We must have continually present to our minds the difference between independence and liberty. Liberty is a right of doing whatever the laws permit, and if a citizen could do what they forbid he would be no longer possessed of liberty, because all his fellow-citizens would have the same power.

3. The Same Object Continued

Democratic and aristocratic states are not in their own nature free. Political liberty is to be found only in moderate governments; and even in these it is not always found. It is there only when there is no abuse of power. But constant experience shows us that every man invested with power is apt to abuse it, and to carry his authority as far as it will go. Is it not strange, though true, to say that virtue itself has need of limits?

To prevent this abuse, it is necessary from the very nature of things that power should be a check to power. A government may be so constituted, as no man shall be compelled to do things to which the law does not oblige him, nor forced to abstain from things which the law permits.

(…)

6. Of the Constitution of England

In every government there are three sorts of power: the legislative; the executive in respect to things dependent on the law of nations; and the executive in regard to matters that depend on the civil law.

By virtue of the first, the prince or magistrate enacts temporary or perpetual laws, and amends or abrogates those that have been already enacted. By the second, he makes peace or war, sends or receives embassies, establishes the public security, and provides against invasions. By the third, he punishes criminals, or determines the disputes that arise between individuals. The latter we shall call the judiciary power, and the other simply the executive power of the state.

The political liberty of the subject is a tranquillity of mind arising from the opinion each person has of his safety. In order to have this liberty, it is requisite the government be so constituted as one man need not be afraid of another.

When the legislative and executive powers are united in the same person, or in the same body of magistrates, there can be no liberty; because apprehensions may arise, lest the same monarch or senate should enact tyrannical laws, to execute them in a tyrannical manner.

Again, there is no liberty, if the judiciary power be not separated from the legislative and executive. Were it joined with the legislative, the life and liberty of the subject would be exposed to arbitrary control; for the judge would be then the legislator. Were it joined to the executive power, the judge might behave with violence and oppression.

There would be an end of everything, were the same man or the same body, whether of the nobles or of the people, to exercise those three powers, that of enacting laws, that of executing the public resolutions, and of trying the causes of individuals.

(…)

The judiciary power ought not to be given to a standing senate; it should be exercised by persons taken from the body of the people at certain times of the year, and consistently with a form and manner prescribed by law, in order to erect a tribunal that should last only so long as necessity requires.

By this method the judicial power, so terrible to mankind, not being annexed to any particular state or profession, becomes, as it were, invisible. People have not then the judges continually present to their view; they fear the office, but not the magistrate.

In accusations of a deep and criminal nature, it is proper the person accused should have the privilege of choosing, in some measure, his judges, in concurrence with the law; or at least he should have a right to except against so great a number that the remaining part may be deemed his own choice.

The other two powers may be given rather to magistrates or permanent bodies, because they are not exercised on any private subject; one being no more than the general will of the state, and the other the execution of that general will.

But though the tribunals ought not to be fixed, the judgments ought; and to such a degree as to be ever conformable to the letter of the law. Were they to be the private opinion of the judge, people would then live in society, without exactly knowing the nature of their obligations.

The judges ought likewise to be of the same rank as the accused, or, in other words, his peers; to the end that he may not imagine he is fallen into the hands of persons inclined to treat him with rigour.

(…)

Questions for Reflection:

1. How does Montesquieu’s separation of powers apply to the Brazilian Supreme Federal Court’s jurisdiction to investigate and judge certain authorities?

2. How does Montesquieu’s separation of powers apply to modern democratic challenges, such as judicial activism?

3. How do you evaluate a judicial body composed of tenured judges serving for life, as opposed to Montesquieu’s prescription of judges elected by the people (by the people of the judge’s region of practice) for temporary terms.

4. In what ways can Montesquieu’s contextual approach to law inform policies that address cultural diversity in a country? Where would you situate Montesquieu’s thinking in relation to federalism?

5. In a panel at COP 28 in Dubai, Justice Luís Roberto Barroso of the Federal Supreme Court stated:

“Constitutional Courts play three types of roles: (i) counter-majoritarian, when they invalidate acts of the other two branches of government that contradict the Constitution; (ii) representative, when they address social demands, protected by the Constitution, that have not been met by the majority political process; and (iii) enlightenment. This enlightenment role can be defined as follows: in certain rare but important situations, it is up to the Supreme Courts, in the name of the Constitution, international treaties, and universal values of justice, to remedy serious omissions that affect human rights. This occurs in cases of government inertia and even social demobilization. In many parts of the world, this was the case with racial segregation, women’s rights, and the rights of the LGBTQIAPN+ community.”

How do the Supreme Court Justice’s “enlightenment” ideas align with or contradict Montesquieu’s? How do these agree with or contradict the U.S. Supreme Court’s defense in the case mentioned in the box “Courts May Not Exceed Their Powers?” How do they agree with or contradict Stephen Miller’s and Thomas Jefferson’s ideas of the absence of judicial supremacy?

6. How does Montesquieu’s assertion that laws must be adapted to the specific people, climate, and customs of a society challenge the application of universal human rights standards in contemporary international law, such as those enforced by the United Nations?

7. In what ways does Montesquieu’s view that political liberty arises from a “tranquility of mind” based on perceived security critique modern surveillance states, where governments use technology to monitor citizens under the guise of protection?

8. Considering the box’s reference to Stephen Miller’s argument against judicial supremacy, how does this align with or diverge from Montesquieu’s limits on judicial power, and what risks does it pose for constitutional checks in ongoing U.S. political conflicts?

Leave a comment