Introduction

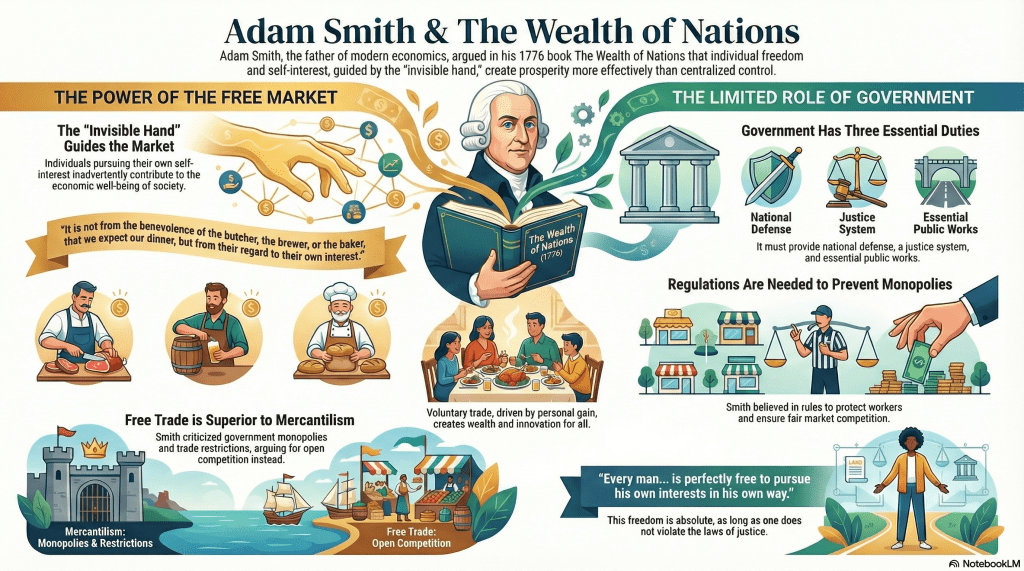

Adam Smith, a Scottish philosopher and economist, is often hailed as the father of modern economics. His landmark work, An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations (1776), introduced the concept of the free market as a mechanism for generating prosperity through individual initiative and voluntary exchange. Writing during the Enlightenment and the early stages of the Industrial Revolution, Smith argued that economic freedom, guided by the “invisible hand” of self-interest, could create wealth and social harmony more effectively than centralized control.

In the circular diagram of political mindsets, Smith is a pillar of the classical liberal perspective, advocating limited government intervention, individual liberty, and market-driven progress, while opposing the mercantilist and authoritarian tendencies of both statist radicals and conservative authoritarians. His ideas shaped modern capitalism and continue to influence debates on economic policy and governance.

Figure: 14 Adam Smith

Author: desconhecido

Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Adam_Smith_The_Muir_portrait.jpg

Smith’s Core Ideas: The Invisible Hand and the Free Market

In The Wealth of Nations, Smith posits that individuals who pursue their own interests inadvertently contribute to the common good through market interactions. He famously quipped:

“It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker, that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest… He aims only at his own gain, and in this, as in many other cases, is guided by an invisible hand to promote an end which was no part of his intention” (The Wealth of Nations, Book IV, Chapter II).

This “invisible hand” metaphor summarizes Smith’s belief that free markets, driven by supply and demand, allocate resources efficiently without the need for strict government control. By pursuing personal gain, individuals create wealth, innovation, and social benefits through voluntary trade. Smith’s emphasis on economic freedom builds on John Locke’s ideas about property and individual rights, extending them to the realm of commerce.

Smith also criticized mercantilism, the dominant economic system of his time, which relied on government monopolies, trade restrictions, and colonial exploitation to accumulate national wealth. He argued that such policies stifled innovation and prosperity, advocating instead for free trade and competition. He writes:

“The natural exertion of every individual to improve his own condition… is so powerful a principle, that alone and without any assistance… it is able to conduct society to wealth and prosperity” (The Wealth of Nations, Book IV, Chapter V).

Smith’s View of Limited Government

While Smith advocated for the free market, he did not advocate for a completely laissez-faire state. He recognized the government’s role in providing public goods—such as defense, justice, and infrastructure—that markets cannot efficiently supply. He writes:

“The third and last duty of the sovereign or commonwealth is to erect and maintain those institutions and public works which…are of such a nature that profit could never repay the expenses of any individual” (The Wealth of Nations, Book V, Chapter I).

Smith also supported regulations to prevent monopolies and protect workers, recognizing that unchecked market power could harm society. This nuanced view distinguishes him from later, more dogmatic interpretations of laissez-faire economics, aligning him with the pragmatic liberalism of Montesquieu, who emphasized balanced governance adapted to the needs of society. Smith’s moral philosophy, outlined in The Theory of Moral Sentiments (1759), further complements his economic thought by emphasizing sympathy and ethical behavior as foundations for social cohesion in a market-oriented society.

Relationship to the Circle Diagram

In the circle diagram of political mindsets, Adam Smith embodies the classical liberal perspective with his advocacy of economic freedom, limited government, and individual initiative. His ideas connect with adjacent groups and contrast with their opposites:

Democratic Leftists: Smith’s support for public goods, such as education and infrastructure, shares common ground with democratic socialists who advocate state intervention for social welfare, though they differ on the extent of economic regulation. His emphasis on prosperity through trade resonates with social democratic policies that balance markets with social welfare, as seen in postwar Scandinavian models.

Moderate Conservatives: Smith’s respect for gradual economic progress and social stability aligns with moderate conservatives who value tradition but embrace market-oriented reforms, such as those championed by Margaret Thatcher. His critique of mercantilist privilege appeals to conservatives wary of entrenched elites.

Opposition to Radical Statists and Authoritarian Conservatives: Smith’s rejection of centralized economic control directly opposes radical statists, such as those in Mussolini’s fascist Italy or Stalin’s Soviet Union, who subordinated markets to state ideology. Similarly, his critique of mercantilist monopolies challenges conservative authoritarians, such as those in Franco’s Spain, who prioritized state-backed hierarchies over economic freedom.

Historical Context and Impact

Smith wrote during a transformative period marked by the Industrial Revolution and the decline of mercantilism. The growing British commercial empire served as a backdrop for his ideas, while trade and industry fueled debates about economic policy. The Wealth of Nations influenced the shift toward free trade in the 19th century, notably through Britain’s repeal of the Corn Laws (1846), which reduced tariffs and promoted open markets. Smith’s ideas also shaped classical liberal economists such as David Ricardo and John Stuart Mill, who refined his theories on trade and markets.

In the United States, Smith’s principles influenced the economic views of the Founding Fathers, particularly Alexander Hamilton’s advocacy of trade, albeit tempered by protectionist policies.

Modern Relevance

Smith’s ideas remain central to economic policy debates. Classical liberals like Friedrich Hayek and Milton Friedman draw on his principles to advocate for deregulation and free trade, while figures like Ron Paul (U.S. Congressman) echo his call for minimal government interference. However, Smith’s nuanced view of the role of government—supporting public goods and curbing monopolies—resonates with moderates seeking a balanced approach to capitalism.

Smith’s vision of markets as engines of prosperity and freedom continues to shape economic thought, reminding us that individual freedom and social wealth are closely intertwined.

| I learned from Adam Smith Margaret Hilda Thatcher, Baroness Thatcher of Kesteven (1925–2013) was a British stateswoman who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom (1979–1990). In her speech to the Toronto Club (1988), she said: “We were not the first in the field. It is called “Thatcherism” . I always say, particularly when I go to Scotland: “You are totally wrong. I learned it from Adam Smith and he was a long time before me!” Adam Smith was not a professor of economics—he was a professor of moral philosophy and he knew what you had to do to get the very best out of human nature. He knew that people will work extremely hard because they work for their families, they work for their future, they work for their own ambitions, they work to build a better future for their families and for their community. Therefore, we introduced incentives and cut our taxation as it was prudent to do so, all the time—if we had to cut direct taxation—balancing it out with an increase in indirect so we did not get an increase in deficit. We cut the controls. This was quite a bold move. I remember when I was in Opposition having many people in like this to talk about what we were going to do and saying to them: “You know, we shall simply have to take off—abolish—foreign exchange controls!” I remember a banker saying: “Well, do not be too hasty! You cannot do that!” So we abolished them! And I met him afterwards and said: “You know, that is the secret of our inward investment. People know that if they come to us they can repatriate their profits and so they are coming to us!” (Full speech at: https://www.margaretthatcher.org/document/107269) |

Conclusion

Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations revolutionized economic thought by demonstrating how the free market, guided by the invisible hand, generates wealth and social well-being through individual initiative. His defense of economic freedom, limited government, and competition cements his place in the classical liberal mindset of the circle diagram, uniting democratic and conservative values while opposing authoritarian control. Smith’s ideas, born of the Enlightenment, laid the foundation for modern capitalism and remain a touchstone for debates about the role of markets and government in promoting prosperity.

Key Quote

“Every man, so long as he does not violate the laws of justice, is perfectly free to pursue his own interests in his own way, and to place his industry and capital in competition with those of every other man” (The Wealth of Nations, Book IV, Chapter IX).

Selected Excerpts

Adam Smith. AN INQUIRY INTO THE NATURE AND CAUSES OF THE WEALTH OF NATIONS.

CHAPTER II. OF THE PRINCIPLE WHICH GIVES OCCASION TO THE DIVISION OF LABOUR

THIS DIVISION OF LABOUR, from which so many advantages are derived, is not originally the effect of any human wisdom, which foresees and intends that general opulence to which it gives occasion. It is the necessary, though very slow and gradual, consequence of a certain propensity in human nature, which has in view no such extensive utility; the propensity to truck, barter, and exchange one thing for another.

Whether this propensity be one of those original principles in human nature, of which no further account can be given, or whether, as seems more probable, it be the necessary consequence of the faculties of reason and speech, it belongs not to our present subject to inquire. It is common to all men, and to be found in no other race of animals, which seem to know neither this nor any other species of contracts. Two greyhounds, in running down the same hare, have sometimes the appearance of acting in some sort of concert. Each turns her towards his companion, or endeavours to intercept her when his companion turns her towards himself.

This, however, is not the effect of any contract, but of the accidental concurrence of their passions in the same object at that particular time. Nobody ever saw a dog make a fair and deliberate exchange of one bone for another with another dog. Nobody ever saw one animal, by its gestures and natural cries signify to another, this is mine, that yours; I am willing to give this for that.

When an animal wants to obtain something either of a man, or of another animal, it has no other means of persuasion, but to gain the favour of those whose service it requires. A puppy fawns upon its dam, and a spaniel endeavours, by a thousand attractions, to engage the attention of its master who is at dinner, when it wants to be fed by him. Man sometimes uses the same arts with his brethren, and when he has no other means of engaging them to act according to his inclinations, endeavours by every servile and fawning attention to obtain their good will. He has not time, however, to do this upon every occasion. In civilized society he stands at all times in need of the co-operation and assistance of great multitudes, while his whole life is scarce sufficient to gain the friendship of a few persons. In almost every other race of animals, each individual, when it is grown up to maturity, is entirely independent, and in its natural state has occasion for the assistance of no other living creature. But man has almost constant occasion for the help of his brethren, and it is in vain for him to expect it from their benevolence only. He will be more likely to prevail if he can interest their self-love in his favour, and shew them that it is for their own advantage to do for him what he requires of them.

Whoever offers to another a bargain of any kind, proposes to do this. Give me that which I want, and you shall have this which you want, is the meaning of every such offer; and it is in this manner that we obtain from one another the far greater part of those good offices which we stand in need of. It is not from the

benevolence of the butcher the brewer, or the baker that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest. We address ourselves, not to their humanity, but to their self-love, and never talk to them of our own necessities, but of their advantages.

Nobody but a beggar chooses to depend chiefly upon the benevolence of his fellow-citizens. Even a beggar does not depend upon it entirely. The charity of well-disposed people, indeed, supplies him with the whole fund of his subsistence. But though this principle ultimately provides him with all the necessaries of life which he has occasion for, it neither does nor can provide him with them as he has occasion for them.

The greater part of his occasional wants are supplied in the same manner as those of other people, by treaty, by barter, and by purchase. With the money which one man gives him he purchases food. The old clothes which another bestows upon him he exchanges for other clothes which suit him better, or for lodging, or for food, or for money, with which he can buy either food, clothes, or lodging, as he has occasion.

As it is by treaty, by barter, and by purchase, that we obtain from one another the greater part of those mutual good offices which we stand in need of, so it is this same trucking disposition which originally gives occasion to the division of labour. In a tribe of hunters or shepherds, a particular person makes bows and arrows, for example, with more readiness and dexterity than any other. He frequently exchanges them for cattle or for venison, with his companions; and he finds at last that he can, in this manner, get more cattle and venison, than if he himself went to the field to catch them. From a regard to his own interest, therefore, the making of bows and arrows grows to be his chief business, and he becomes a sort of armourer. Another excels in making the frames and covers of their little huts or moveable houses. He is accustomed to be of use in this way to his neighbours, who reward him in the same manner with cattle and with venison, till at last he finds it his interest to dedicate himself entirely to this employment, and to become a sort of house-carpenter. In the same manner a third becomes a smith or a brazier; a fourth, a tanner or dresser of hides or skins, the principal part of the clothing of savages. And thus the certainty of being able to exchange all that surplus part of the produce of his own labour, which is over and above his own consumption, for such parts of the produce of other men’s labour as he may have occasion for, encourages every man to apply himself to a particular occupation, and to cultivate and bring to perfection whatever talent of genius he may possess for that particular species of business.

The difference of natural talents in different men, is, in reality, much less than we are aware of; and the very different genius which appears to distinguish men of different professions, when grown up to maturity, is not upon many occasions so much the cause, as the effect of the division of labour. The difference between the most dissimilar characters, between a philosopher and a common street porter, for example, seems to arise not so much from nature, as from habit, custom, and education. When they came in to the world, and for the first six or eight years of their existence, they were, perhaps, very much alike, and neither their parents nor playfellows could perceive any remarkable difference. About that age, or soon after, they come to be employed in very different occupations. The difference of talents comes then to be taken notice of, and widens by degrees, till at last the vanity of the philosopher is willing to acknowledge scarce any resemblance. But without the disposition to truck, barter, and exchange, every man must have procured to himself every necessary and conveniency of life which he wanted. All must have had the same duties to perform, and the same work to do, and there could have been no such difference of employment as could alone give occasion to any great difference of talents.

As it is this disposition which forms that difference of talents, so remarkable among men of different professions, so it is this same disposition which renders that difference useful. Many tribes of animals, acknowledged to be all of the same species, derive from nature a much more remarkable distinction of genius, than what, antecedent to custom and education, appears to take place among men. By nature a philosopher is not in genius and disposition half so different from a street porter, as a mastiff is from a grey-hound, or a grey-hound from a spaniel, or this last from a shepherd’s dog.

Those different tribes of animals, however, though all of the same species are of scarce any use to one another. The strength of the mastiff is not in the least supported either by the swiftness of the greyhound, or by the sagacity of the spaniel, or by the docility of the shepherd’s dog. The effects of those different geniuses and talents, for want of the power or disposition to barter and exchange, cannot be brought into a common stock, and do not in the least contribute to the better accommodation and conveniency of the species. Each animal is still obliged to support and defend itself, separately and independently, and derives no sort of advantage from that variety of talents with which nature has distinguished its fellows. Among men, on the contrary, the most dissimilar geniuses are of use to one another; the different produces of their respective talents, by the general disposition to truck, barter, and exchange, being brought, as it were, into a common stock, where every man may purchase whatever part of the produce of other men’s talents he has occasion for.

Questions for Reflection

1. How does Smith’s concept of the invisible hand align or conflict with the idea of regulatory agencies?

2. How might Smith’s support for public goods align or conflict with contemporary welfare state policies?

3. How would Smith’s critique of mercantilism address current debates on tariffs and protectionism?

4. Why is such a relevant concept as the invisible hand so often overlooked in public policymaking?

5. Discuss Smith’s critique of mercantilism and advocacy for free markets through voluntary exchange; how could this inform current debates on trade policies, such as tariffs and protectionism in ongoing U.S.-China trade tensions?

6. How might Smith’s emphasis on the natural exertion of individuals to improve their condition without government assistance critique contemporary interventionist policies, such as subsidies for green energy or bailouts during economic crises?

7. In what ways does Smith’s support for regulations to protect workers and prevent monopolies underscore the need for antitrust actions in modern tech industries, such as ongoing lawsuits against companies like Google or Amazon?

8. How does Smith’s observation that virtue is more important than good government—”all government is but an imperfect remedy for deficiency of wisdom and virtue”—apply to contemporary crises of institutional trust and political polarization?

Leave a comment