Introduction

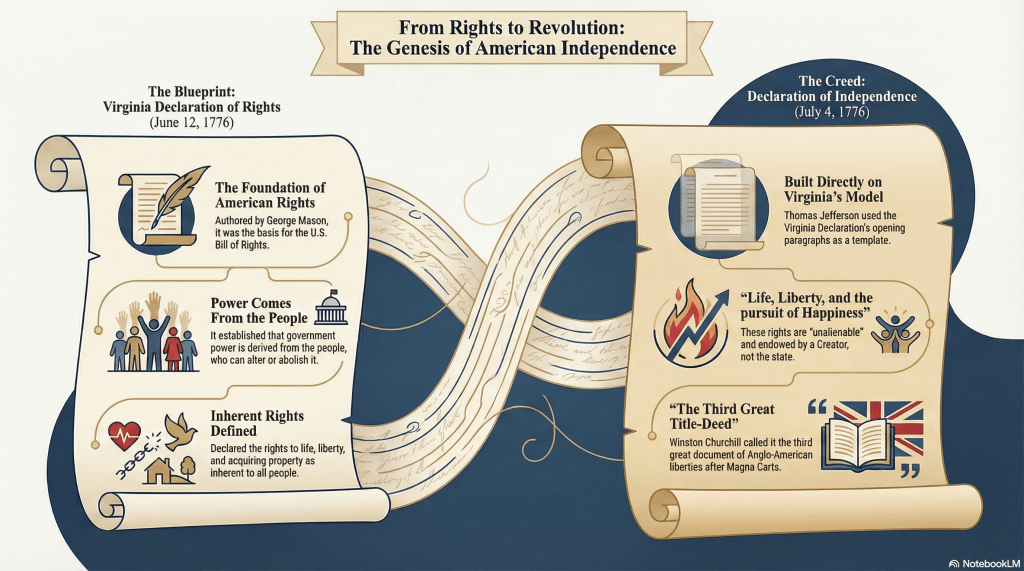

The Virginia Declaration of Rights, written by George Mason (1725-1792), a politician and one of the Founding Fathers of the United States, was adopted by the Virginia Constitutional Convention on June 12, 1776. This declaration was used by Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826), one of the Founding Fathers of the United States and the third president of the United States, for the opening paragraphs of the Declaration of Independence. It was also widely copied by the other colonies and became the basis of the Bill of Rights.

The American Declaration of Independence, adopted on July 4, 1776, is a fundamental example of classical liberal thought. It emphasizes individual liberty, limited government, and natural rights, drawing heavily from the philosophy of John Locke. The Declaration states: “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness,” emphasizing these rights as inherent, not guaranteed by the State.

Historical and Philosophical Context

The American Revolution (1765–1783) was driven by the defense of natural rights, rooted in the philosophy of John Locke, which influenced figures such as Thomas Jefferson and John Adams.

The Virginia Declaration, adopted on June 12, 1776, is the foundational document of the American Bill of Rights, establishing principles such as natural equality, the right to life, liberty, and property, that all power emanates from the people, that judges and public officers exercise power in the name of the people, and the need for a government to protect these rights, among others.

The Declaration of Independence, adopted on July 4, 1776, is a pivotal document, beginning with:

“When, in the Course of human events, it becomes necessary for one people to dissolve the political bands which have connected them with another, and to assume, among the powers of the earth, that separate and equal station to which the Laws of Nature and of Nature’s God entitle them…”

This opening reflects the belief that the American republic is rooted in natural law, supported by reason and divine revelation. God is mentioned four times in the Declaration, each with a specific role:

“Laws of Nature and of Nature’s God” as the legislative basis;

“endowed by their Creator” as the origin of unalienable rights;

“Supreme Judge of the world” as the judge of the rebellious cause;

“protection of divine Providence” as the executive role.

This view combines the Protestant tradition, predominant among the colonists (an estimated 98% of them were Protestants), with Enlightenment philosophy, aligning with Locke’s social contract theory.

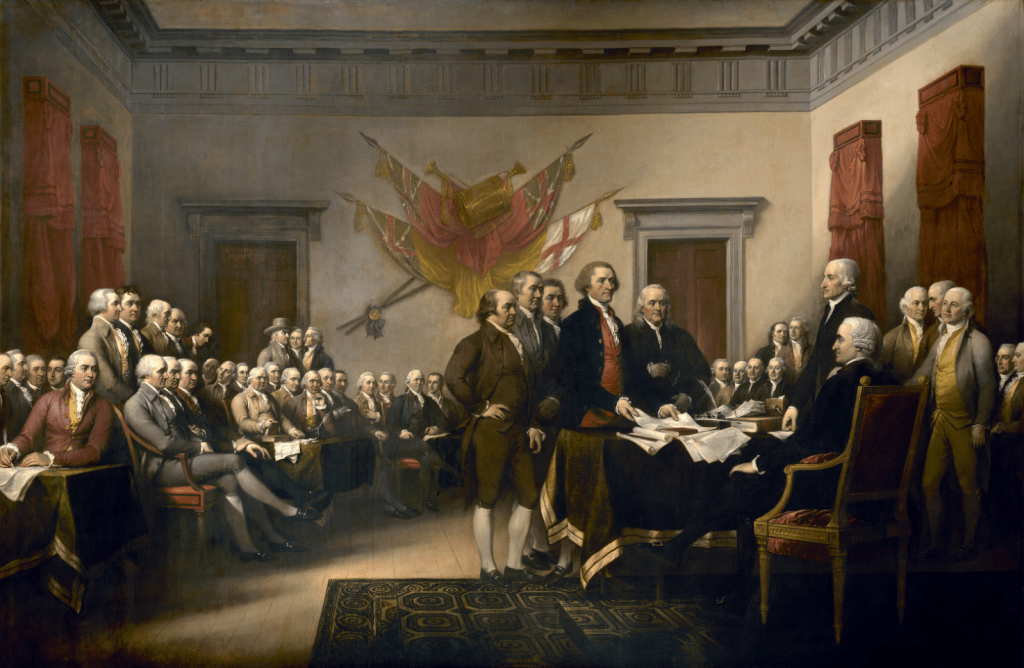

Figure 15: Declaration of Independence.

Author: John Trumbull (1756-1843)

Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Declaration_of_Independence_(1819),_by_John_Trumbull.jpg

| What makes America unique On his speech “What I saw in America, Gilbert Keith Chesterton (1874-1936) said: “America is the only nation in the world that is founded on a creed. That creed is set forth with dogmatic and even theological lucidity in the Declaration of Independence; perhaps the only piece of practical politics that is also theoretical politics and also great literature. It enunciates that all men are equal in their claim to justice, that governments exist to give them that justice, and that their authority is for that reason just. It certainly does condemn anarchism, and it does also by inference condemn atheism, since it clearly names the Creator as the ultimate authority from whom these equal rights are derived. Nobody expects a modern political system to proceed logically in the application of such dogmas, and in the matter of God and Government it is naturally God whose claim is taken more lightly. The point is that there is a creed, if not about divine, at least about human things” |

Some Lessons from the American Revolution

Considered the paradigm of revolutionary success, some lessons can be drawn from the American Revolution, reflecting its principles and practices:

Legitimacy of the Revolution: A revolution is legitimate if it aims to remove a government that systematically and for a prolonged period violates God-given and natural rights, when there is no longer any hope for common sense (and respect for such rights) in government action. The Declaration of Independence justifies this by listing abuses of King George III, such as the imposition of taxes without representation.

Civility in the Revolution: Even to make a revolution, it is possible to be civilized, but all resources must be tried beforehand. The colonists exhausted peaceful means, such as petitions and negotiations, before resorting to violence, illustrating that revolution is a last resort.

| The fight to end slavery from the beginning Thomas Jefferson included a strong condemnation of the transatlantic slave trade in his original draft of the Declaration of Independence, attributing it directly to King George III as a violation of human rights and an “execrable commerce”: ” he has waged cruel war against human nature itself, violating it’s most sacred rights of life & liberty in the persons of a distant people who never offended him, captivating & carrying them into slavery in another hemisphere, or to incur miserable death in their transportation thither. this piratical warfare, the opprobrium of infidel powers, is the warfare of the CHRISTIAN king of Great Britain. determined to keep open a market where MEN should be bought & sold, he has prostituted his negative for suppressing every legislative attempt to prohibit or to restrain this execrable commerce: and that this assemblage of horrors might want no fact of distinguished die, he is now exciting those very people to rise in arms among us, and to purchase that liberty of which he has deprived them, & murdering the people upon whom he also obtruded them; thus paying off former crimes committed against the liberties of one people, with crimes which he urges them to commit against the lives of another.” (full text at: https://www.loc.gov/exhibits/declara/ruffdrft.html) However, the colonies were deeply divided on slavery. According to Jefferson in his autobiography, the clause “reprobating the enslaving the inhabitants of Africa, was struck out in compliance to South Carolina and Georgia, who had never attempted to restrain the importation of slaves, and who on the contrary still wished to continue it” (avaliable at https://www.gutenberg.org/files/45847/45847-h/45847-h.htm). Ultimately, Congress made substantial changes, eliminating the denunciation of the African slave trade, out of a need for consensus among all the colonies. This omission foreshadowed future conflicts that would culminate in the Civil War. |

Relationship with the Circular Diagram of Political Mentalities

In the circular diagram, the American Revolution occupies a central position in classical liberalism, advocating individual liberty and the protection of natural rights. They connect:

To democratic leftists through their emphasis on representation and equality before the law, although they differ on economic intervention, as seen in the slogan “no taxation without representation,” which resonates with movements for universal suffrage.

To moderate conservatives (British and American) through their respect for institutions and gradual change, such as the evolution of the British system, but differing in their emphasis on individual liberty. On the other hand, rights, for British conservatives, originate from pacts with the government; they are not natural or God-given rights.

In contrast, they reject radical statists, such as the absolutism of King George III, defending a system that distributes power and protects liberties, contrasting with centralized regimes like those of Mussolini or Stalin.

| The Third Great Title-Deed of Anglo-American Liberties Winston S. Churchill (1878-1965), the most important British politician of the first half of the 20th century, delivered a speech in honor of the 142nd anniversary of the Declaration of Independence, on July 4, 1918, from which we transcribe excerpts: “I move that the following resolution be cabled from the meeting as a greeting to the President and people of the United States of America: This meeting of the Anglo-Saxon Fellowship assembled in London on the 4th of July, 1918, send to the President and people of the United States their heartfelt greetings on the 142nd anniversary of the Declaration of American Independence. They rejoice that the love of liberty and justice on which the American nation was founded should in the present time of trial have united the whole English-speaking family in a brotherhood of arms. We are met here to-day at Westminster to celebrate the national festival of the American people and the 142nd anniversary of the Declaration of Independence. We are met here also as brothers-in-arms facing for a righteous cause grave injuries and perils and passing through times of exceptional anxiety and suffering. We therefore seek to draw from the past history of our race inspiration and comfort to cheer our hearts and fortify and purify our resolution and our comradeship. A great harmony exists between the spirit and language of the Declaration of Independence and all we are fighting for now. A similar harmony exists between the principles of that Declaration and all that the British people have wished to stand for, and have in fact achieved at last both here at home and in the self-governing Dominions of the Crown. The Declaration of Independence is not only an American document. It follows on Magna Carta and the Bill of Rights as the third great title-deed on which the liberties of the English-speaking people are founded. By it we lost an Empire, but by it we also preserved an Empire. By applying its principles and learning its lesson we have maintained our communion with the powerful Commonwealths our children have established beyond the seas. Wherever men seek to frame politics or constitutions which safeguard the citizen, be he rich or poor, on the one hand from the shame of despotism, on the other from the miseries of anarchy, which combine personal freedom with respect for law and love of country, it is to the inspiration which originally sprang from the English soil and from the Anglo-Saxon mind that they will inevitably recur. We therefore join in perfect sincerity and simplicity with our American kith and kin in celebrating the auspicious and glorious anniversary of their nationhood.” (https://winstonchurchill.hillsdale.edu/churchill-on-july-4th/) |

Modern Relevance

These ideals continue to influence debates about individual liberty versus state intervention, connecting to classical liberalism.

The principles of natural rights and limited government remain central to modern democracies, such as the United States.

Conclusion

The Virginia Declaration and the Declaration of Independence represent the essence of classical liberalism, being central elements of the founding of the United States. They connect to the circular diagram with defenders of liberty, opposing authoritarianism, and remain relevant documents in modern debates about governance, rights, and American constitutional interpretation.

Selected Texts

The Virginia Declaration of Rights (https://www.archives.gov/founding-docs/virginia-declaration-of-rights

A Declaration of Rights

Is made by the representatives of the good people of Virginia, assembled in full and free convention which rights do pertain to them and their posterity, as the basis and foundation of government.

Section 1. That all men are by nature equally free and independent and have certain inherent rights, of which, when they enter into a state of society, they cannot, by any compact, deprive or divest their posterity; namely, the enjoyment of life and liberty, with the means of acquiring and possessing property, and pursuing and obtaining happiness and safety.

Section 2. That all power is vested in, and consequently derived from, the people; that magistrates are their trustees and servants and at all times amenable to them.

Section 3. That government is, or ought to be, instituted for the common benefit, protection, and security of the people, nation, or community; of all the various modes and forms of government, that is best which is capable of producing the greatest degree of happiness and safety and is most effectually secured against the danger of maladministration. And that, when any government shall be found inadequate or contrary to these purposes, a majority of the community has an indubitable, inalienable, and indefeasible right to reform, alter, or abolish it, in such manner as shall be judged most conducive to the public weal.

Section 4. That no man, or set of men, is entitled to exclusive or separate emoluments or privileges from the community, but in consideration of public services; which, nor being descendible, neither ought the offices of magistrate, legislator, or judge to be hereditary.

Section 5. That the legislative and executive powers of the state should be separate and distinct from the judiciary; and that the members of the two first may be restrained from oppression, by feeling and participating the burdens of the people, they should, at fixed periods, be reduced to a private station, return into that body from which they were originally taken, and the vacancies be supplied by frequent, certain, and regular elections, in which all, or any part, of the former members, to be again eligible, or ineligible, as the laws shall direct.

Section 6. That elections of members to serve as representatives of the people, in assembly ought to be free; and that all men, having sufficient evidence of permanent common interest with, and attachment to, the community, have the right of suffrage and cannot be taxed or deprived of their property for public uses without their own consent or that of their representatives so elected, nor bound by any law to which they have not, in like manner, assented, for the public good.

Section 7. That all power of suspending laws, or the execution of laws, by any authority, without consent of the representatives of the people, is injurious to their rights and ought not to be exercised.

Section 8. That in all capital or criminal prosecutions a man has a right to demand the cause and nature of his accusation, to be confronted with the accusers and witnesses, to call for evidence in his favor, and to a speedy trial by an impartial jury of twelve men of his vicinage, without whose unanimous consent he cannot be found guilty; nor can he be compelled to give evidence against himself; that no man be deprived of his liberty except by the law of the land or the judgment of his peers.

Section 9. That excessive bail ought not to be required, nor excessive fines imposed, nor cruel and unusual punishments inflicted.

Section 10. That general warrants, whereby an officer or messenger may be commanded to search suspected places without evidence of a fact committed, or to seize any person or persons not named, or whose offense is not particularly described and supported by evidence, are grievous and oppressive and ought not to be granted.

Section 11. That in controversies respecting property, and in suits between man and man, the ancient trial by jury is preferable to any other and ought to be held sacred.

Section 12. That the freedom of the press is one of the great bulwarks of liberty, and can never be restrained but by despotic governments.

Section 13. That a well-regulated militia, composed of the body of the people, trained to arms, is the proper, natural, and safe defense of a free state; that standing armies, in time of peace, should be avoided as dangerous to liberty; and that in all cases the military should be under strict subordination to, and governed by, the civil power.

Section 14. That the people have a right to uniform government; and, therefore, that no government separate from or independent of the government of Virginia ought to be erected or established within the limits thereof.

Section 15. That no free government, or the blessings of liberty, can be preserved to any people but by a firm adherence to justice, moderation, temperance, frugality, and virtue and by frequent recurrence to fundamental principles.

Section 16. That religion, or the duty which we owe to our Creator, and the manner of discharging it, can be directed only by reason and conviction, not by force or violence; and therefore all men are equally entitled to the free exercise of religion, according to the dictates of conscience; and that it is the mutual duty of all to practise Christian forbearance, love, and charity toward each other.

Declaration of Independence (https://www.archives.gov/founding-docs/declaration-transcript)

In Congress, July 4, 1776

The unanimous Declaration of the thirteen united States of America, When in the Course of human events, it becomes necessary for one people to dissolve the political bands which have connected them with another, and to assume among the powers of the earth, the separate and equal station to which the Laws of Nature and of Nature’s God entitle them, a decent respect to the opinions of mankind requires that they should declare the causes which impel them to the separation.

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.–That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed, –That whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government, laying its foundation on such principles and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness. Prudence, indeed, will dictate that Governments long established should not be changed for light and transient causes; and accordingly all experience hath shewn, that mankind are more disposed to suffer, while evils are sufferable, than to right themselves by abolishing the forms to which they are accustomed. But when a long train of abuses and usurpations, pursuing invariably the same Object evinces a design to reduce them under absolute Despotism, it is their right, it is their duty, to throw off such Government, and to provide new Guards for their future security.–Such has been the patient sufferance of these Colonies; and such is now the necessity which constrains them to alter their former Systems of Government. The history of the present King of Great Britain is a history of repeated injuries and usurpations, all having in direct object the establishment of an absolute Tyranny over these States. To prove this, let Facts be submitted to a candid world.

He has refused his Assent to Laws, the most wholesome and necessary for the public good.

He has forbidden his Governors to pass Laws of immediate and pressing importance, unless suspended in their operation till his Assent should be obtained; and when so suspended, he has utterly neglected to attend to them.

He has refused to pass other Laws for the accommodation of large districts of people, unless those people would relinquish the right of Representation in the Legislature, a right inestimable to them and formidable to tyrants only.

He has called together legislative bodies at places unusual, uncomfortable, and distant from the depository of their public Records, for the sole purpose of fatiguing them into compliance with his measures.

He has dissolved Representative Houses repeatedly, for opposing with manly firmness his invasions on the rights of the people.

He has refused for a long time, after such dissolutions, to cause others to be elected; whereby the Legislative powers, incapable of Annihilation, have returned to the People at large for their exercise; the State remaining in the mean time exposed to all the dangers of invasion from without, and convulsions within.

He has endeavoured to prevent the population of these States; for that purpose obstructing the Laws for Naturalization of Foreigners; refusing to pass others to encourage their migrations hither, and raising the conditions of new Appropriations of Lands.

He has obstructed the Administration of Justice, by refusing his Assent to Laws for establishing Judiciary powers.

He has made Judges dependent on his Will alone, for the tenure of their offices, and the amount and payment of their salaries.

He has erected a multitude of New Offices, and sent hither swarms of Officers to harrass our people, and eat out their substance.

He has kept among us, in times of peace, Standing Armies without the Consent of our legislatures.

He has affected to render the Military independent of and superior to the Civil power.

He has combined with others to subject us to a jurisdiction foreign to our constitution, and unacknowledged by our laws; giving his Assent to their Acts of pretended Legislation:

For Quartering large bodies of armed troops among us:

For protecting them, by a mock Trial, from punishment for any Murders which they should commit on the Inhabitants of these States:

For cutting off our Trade with all parts of the world:

For imposing Taxes on us without our Consent:

For depriving us in many cases, of the benefits of Trial by Jury:

For transporting us beyond Seas to be tried for pretended offences:

For abolishing the free System of English Laws in a neighbouring Province, establishing therein an Arbitrary government, and enlarging its Boundaries so as to render it at once an example and fit instrument for introducing the same absolute rule into these Colonies:

For taking away our Charters, abolishing our most valuable Laws, and altering fundamentally the Forms of our Governments:

For suspending our own Legislatures, and declaring themselves invested with power to legislate for us in all cases whatsoever.

He has abdicated Government here, by declaring us out of his Protection and waging War against us.

He has plundered our seas, ravaged our Coasts, burnt our towns, and destroyed the lives of our people.

He is at this time transporting large Armies of foreign Mercenaries to compleat the works of death, desolation and tyranny, already begun with circumstances of Cruelty & perfidy scarcely paralleled in the most barbarous ages, and totally unworthy the Head of a civilized nation.

He has constrained our fellow Citizens taken Captive on the high Seas to bear Arms against their Country, to become the executioners of their friends and Brethren, or to fall themselves by their Hands.

He has excited domestic insurrections amongst us, and has endeavoured to bring on the inhabitants of our frontiers, the merciless Indian Savages, whose known rule of warfare, is an undistinguished destruction of all ages, sexes and conditions.

In every stage of these Oppressions We have Petitioned for Redress in the most humble terms: Our repeated Petitions have been answered only by repeated injury. A Prince, whose character is thus marked by every act which may define a Tyrant, is unfit to be the ruler of a free people.

Nor have We been wanting in attentions to our Brittish brethren. We have warned them from time to time of attempts by their legislature to extend an unwarrantable jurisdiction over us. We have reminded them of the circumstances of our emigration and settlement here. We have appealed to their native justice and magnanimity, and we have conjured them by the ties of our common kindred to disavow these usurpations, which, would inevitably interrupt our connections and correspondence. They too have been deaf to the voice of justice and of consanguinity. We must, therefore, acquiesce in the necessity, which denounces our Separation, and hold them, as we hold the rest of mankind, Enemies in War, in Peace Friends.

We, therefore, the Representatives of the united States of America, in General Congress, Assembled, appealing to the Supreme Judge of the world for the rectitude of our intentions, do, in the Name, and by Authority of the good People of these Colonies, solemnly publish and declare, That these United Colonies are, and of Right ought to be Free and Independent States; that they are Absolved from all Allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political connection between them and the State of Great Britain, is and ought to be totally dissolved; and that as Free and Independent States, they have full Power to levy War, conclude Peace, contract Alliances, establish Commerce, and to do all other Acts and Things which Independent States may of right do. And for the support of this Declaration, with a firm reliance on the protection of divine Providence, we mutually pledge to each other our Lives, our Fortunes and our sacred Honor.

Reflection Questions

1. How did the principles of the Declaration of Independence influence the structure of the federal government in the United States?

2. How do the ideals of the American Revolution relate to contemporary political mindsets, such as classical liberalism and conservatism?

3. Why does the Virginia Declaration speak of the right to property (section 1) and the Declaration of Independence speak of the right to the pursuit of happiness (paragraph 2)? Are they talking about different things? Or, to what extent are these two rights (property and the pursuit of happiness) intertwined?

4. Is the right to remove a persistently unjust government (the right of revolution) a right in the legal sense (provided for in legal norms and guaranteed by the Judiciary), or is it a natural right or a God-given right that is asserted not as a justification of actions before men but as a justification before God (“the Supreme Judge of the world,” in the last paragraph of the Declaration of Independence)?

5. The Virginia Declaration states that “the military shall be strictly subordinate to, and governed by, the civil power.” The Declaration of Independence identifies the attempt to “render the military independent of, and superior to, the civil power” as the cause of the revolution. In Brazil, the military held power from 1964 to 1985, with broad support from political groups and a portion of the population. Given these considerations, in the Circular Diagram of Political Mentalities, where would these political groups and this portion of the population best be classified?

6. Brazil is experiencing a dictatorship of the Judiciary in collusion with the Executive Branch. If, hypothetically, you were tasked with making a declaration of independence from this consortium, what principles would you enunciate in that declaration? What facts would you relate to it?

Leave a comment