The Federalists papers

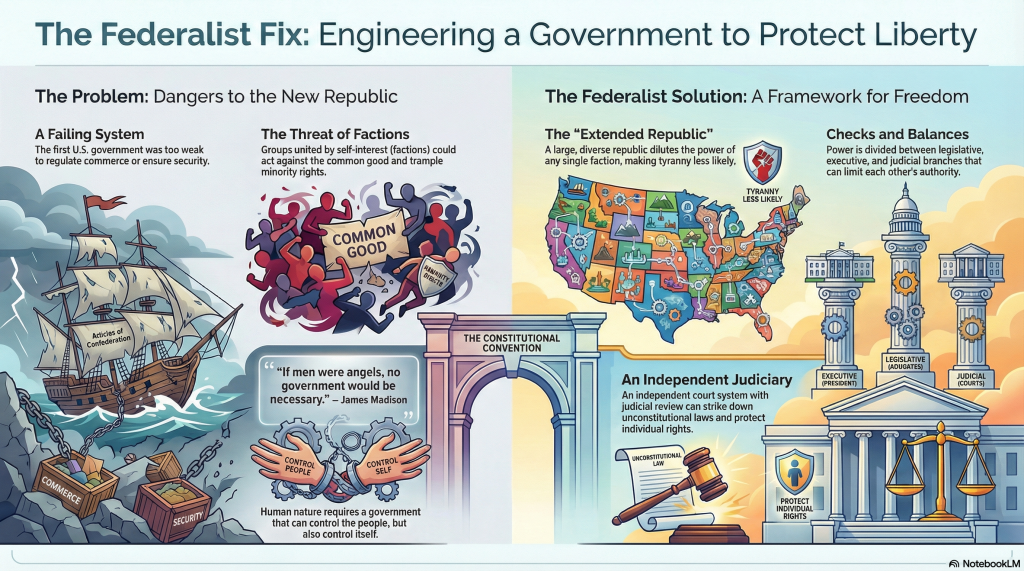

Following the American Revolution, the newly independent United States faced the monumental task of designing a government capable of uniting diverse states while preserving individual liberty and preventing tyranny. The Articles of Confederation, the nation’s first attempt at governance, proved inadequate due to its weak central authority, inability to regulate commerce, and lack of enforcement mechanisms. The Constitutional Convention of 1787 produced a new Constitution, which the Federalists—led by Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay—defended through The Federalist Papers, a series of 85 essays published between 1787 and 1788 under the pseudonym Publius. These essays articulated a vision for a federal government that was strong enough to ensure stability and security but limited enough to safeguard liberty, aligning with the principles of classical liberalism.Key Federalist Papers and Their Arguments

- Federalist No. 1 (Hamilton)

Hamilton introduces the series by framing the Constitution as a unique opportunity to establish a government “by reflection and choice” rather than through force or historical accident. He emphasizes the need for a strong but limited federal government to preserve the union, protect individual liberties, and ensure national security. This vision rejected both the anarchy of an overly weak government and the tyranny of an overly centralized one, setting the tone for a balanced approach to governance. - Federalist No. 10 (Madison)

Madison tackles the problem of factions—groups united by shared interests that may act against the common good or the rights of others. He argues that factions are inevitable due to human nature’s diversity of opinions, passions, and interests. However, a large, diverse republic mitigates their dangers by making it harder for any single faction to dominate. This “extended republic” theory contrasts with smaller democracies, where a majority could easily oppress minorities. Madison’s solution promotes pluralism, ensuring that competing interests balance each other, protecting both majority rule and minority rights. - Federalist No. 51 (Madison)

Madison elaborates on the separation of powers and checks and balances, arguing that each branch of government—legislative, executive, and judicial—must have its own “will” to prevent any one branch from dominating. He famously states, “If men were angels, no government would be necessary,” acknowledging human imperfection as the basis for institutional safeguards. Federalism itself serves as an additional check, with state and federal governments counterbalancing each other. This dual sovereignty ensures that power is distributed, reducing the risk of centralized tyranny. - Federalist No. 78 (Hamilton)

Hamilton defends the judiciary’s role, particularly the concept of judicial review, which allows courts to strike down laws that violate the Constitution. He argues that an independent judiciary, with judges appointed for life (subject to good behavior), is essential to protect constitutional principles and individual rights against legislative overreach or popular passions. This essay underscores the judiciary’s role as a guardian of the rule of law, a cornerstone of limited government.

Figure 16: Hamilton

Autor: Daniel Huntington

Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Alexander_Hamilton#/media/File:Hamilton_small.jpg

These essays collectively advocate for a federal government that is robust yet restrained, rooted in the principles of classical liberalism: individual liberty, limited government, and the protection of natural rights.

| The Moral Foundation of Liberty America’s Founding Fathers recognized that a free society depends not only on institutional design but also on the character of its people. Among them, John Adams (1735-1826), the second President of the United States (1797-1801), famously declared in a 1798 letter: “Our Constitution was made only for a moral and religious people. It is utterly inadequate for the government of any other.” This reflects the belief of America’s Founding Fathers that self-governance requires a virtuous citizenry capable of exercising moderation, respecting the rule of law, and prioritizing the common good. While the Constitution establishes legal limits, its success depends on a population guided by moral principles derived from religion. |

Core Lessons from the Federalists

The Federalists’ arguments yield several enduring lessons for governance:

- Union as a Safeguard of Liberty

The Federalist Papers, particularly No. 10, argue that a strong union protects against external threats (e.g., foreign aggression) and internal discord (e.g., interstate conflicts). A united republic fosters peace among states and ensures collective security, allowing the nation to thrive without the constant threat of division or war. - The Necessity of Government

Madison’s assertion in Federalist No. 51 that governments are necessary because “men are not angels” acknowledges human tendencies toward self-interest and conflict. A structured government channels these tendencies into orderly processes, preventing chaos and ensuring justice. - Controlling Government Power

Because rulers are also fallible, governments must be constrained. Federalist No. 51’s advocacy for checks and balances—through separation of powers and federalism—ensures that no single entity wields unchecked authority. This system prevents tyranny by distributing power across multiple institutions and levels of government. - Mitigating Factions

Madison’s solution to factions in Federalist No. 10 is pragmatic: since factions arise from human nature, their causes cannot be eliminated without suppressing liberty. Instead, their effects can be controlled through:- A Large Republic: A diverse population and vast territory dilute the influence of any single faction.

- Representative Government: Delegating authority to elected officials filters popular passions through deliberation.

- Legislative Representation: Laws crafted by representatives reflect broader interests, reducing factional dominance.

- Controlling the Legislature

Madison notes in Federalist No. 51 that the legislature, as the branch closest to the people, tends to dominate in a republic. To counter this, he advocates for a bicameral legislature, with the Senate and House of Representatives elected differently (originally, senators were chosen by state legislatures, ensuring state influence). This division fragments legislative power, preventing hasty or oppressive laws.

| The National Health Foundation and Brazilian Federalism Upon reviewing the “Evaluation of Funasa’s Strategy and Action Plan” process (TC 010.658/2018-1), the Court issued Ruling 2359/2018-Plenary, the preceding report of which contains, among other things, the following policy analyses: “Thus, applying 92% to the operating budget of R$5,193,093,987.11, according to data obtained from non-digitizable items, file ‘Siop Budget – 2013-2017 with analysis.xlsx’, linked to exhibit 14 of the case file, it follows that R$4,777,646,468.14 was allocated to ensure the delivery of the works during this interregnum. Since, during the period analyzed, according to information presented by Funasa, 1,889 projects were delivered, Funasa’s maintenance cost per completed project was R$2,529,193.47 (R$4,777,646,468.14/1889).(…) When assessing how many projects completed between 2013 and 2017 actually cost over R$2,500,000.00, the approximate cost of Funasa’s funding per project delivered, it was found that only 127 projects were delivered, or 6.72% of the total. In other words, more than 90% of the projects Funasa managed to deliver between 2013 and 2017 cost less than the federal government’s necessary contribution to ensure its operation and delivery of this result. 182. This finding demonstrates that Funasa’s operational model, which prioritizes the delivery of sanitation projects, is not economically sustainable, given that most projects cost less than what is necessary to cover the entity’s funding and enable the delivery of these products. (…) Based on this framework, it can be seen that Funasa’s situation reported in this topic indicates that the sanitation policy established by it is not based on a prior analysis of the cost-benefit ratio in its implementation. Therefore, we have implemented an inefficient public policy that, in order to deliver R$1,651,967,459.50 in sanitation projects between 2013 and 2017, had to spend R$4,777,646,468.14 on the activities necessary to implement its policy during that same period. 185. In other words, almost three times more budgetary resources were allocated from the public treasury to fund Funasa than to the execution of the sanitation projects themselves. This disparity highlights the inefficiency of the public policy in question, since the Federal Government, in order to deliver a relevant product to society (sanitation projects), must spend more than three times the amount required to carry out the project itself. (…)“ |

The Federalists in the Political Spectrum

In the “circular diagram of political mentalities,” the Federalists occupy a central position within classical liberalism, emphasizing individual liberty, limited government, and natural rights. Their ideas connect to and diverge from other ideologies:

- Democratic Leftists: The Federalists share with democratic leftists a commitment to representation and equality before the law, as seen in the revolutionary slogan “no taxation without representation.” However, they diverge on economic intervention, as Federalists prioritized economic liberty and were wary of excessive government involvement, unlike modern leftists who often advocate for redistribution or regulation.

- Moderate Conservatives: The Federalists align with conservative respect for institutions and gradual change, drawing inspiration from the British constitutional tradition. However, they differ in their view of rights: Federalists saw rights as natural or God-given, whereas British conservatives viewed them as derived from historical compacts with the state.

- Opposition to Radical Statists: The Federalists vehemently opposed centralized, authoritarian systems, such as the absolutism of King George III or later totalitarian regimes like those of Mussolini or Stalin. Their system of distributed power and protected liberties stands in stark contrast to statist ideologies that concentrate authority.

Philosophical Underpinnings

The Federalists’ ideas were deeply rooted in Enlightenment thought, particularly the works of John Locke, Montesquieu, and David Hume. Locke’s concept of natural rights—life, liberty, and property—underpins their view of government as a protector of inherent freedoms. Montesquieu’s theory of separation of powers directly influenced their institutional design, while Hume’s realism about human nature informed Madison’s approach to factions and checks and balances. The Federalists also drew on classical republicanism, emphasizing civic virtue and the common good, as seen in Adams’ emphasis on a moral populace.

| The Judiciary Act of 1802 The Judiciary Act of 1802, formally titled “An Act to amend the Judicial System of the United States,” was a federal statute enacted on April 29, 1802, during the administration of President Thomas Jefferson. It primarily served to repeal and replace the controversial Judiciary Act of 1801 (also known as the Midnight Judges Act), which had been passed by the outgoing Federalist-controlled Congress under President John Adams to expand the federal judiciary and appoint new judges before the transition to Republican (Jeffersonian) control. Historical Context The 1801 Act restructured the federal courts by reducing the number of Supreme Court justices from six to five (effective upon the next vacancy), creating 16 new circuit court judgeships, and relieving Supreme Court justices of their circuit-riding duties (traveling to preside over lower courts). Adams appointed Federalist allies to these new positions in his final days in office, which Republicans viewed as an attempt to entrench Federalist influence in the judiciary. After Jefferson’s Republicans gained majorities in Congress following the 1800 elections, they moved quickly to undo these changes. The repeal process began in January 1802, leading to the full Act in April. Key Provisions The Act made several significant changes to restore and modify the federal court system originally outlined in the Judiciary Act of 1789: Repeal of the 1801 Act: It abolished the 16 new circuit judgeships created in 1801, effectively removing the “midnight judges” from office (though some were reassigned or compensated). Circuit Reorganization: The number of federal judicial circuits was increased from three to six, with each Supreme Court justice assigned to preside over one circuit. This reinstated the justices’ circuit-riding duties but in a more manageable form (one justice per circuit instead of pairs). Supreme Court Sessions: The Act reduced Supreme Court sessions from two per year to one (held in February), and it postponed the Court’s next session until 1803 to prevent immediate challenges to the repeal. District Courts: It expanded the authority of district judges in certain cases and adjusted court sessions and jurisdictions to align with the new circuit structure. These changes aimed to balance efficiency with Republican priorities, reducing Federalist appointees while maintaining a functional judiciary. Impact and Legacy The precedent set by the Judiciary Act of 1802 remains valid and fundamental to the modern understanding of Congress’s power over the federal judiciary. Historical practice and constitutional interpretation continue to affirm that Congress can establish, reorganize, or abolish lower federal courts, adjust Supreme Court procedures (e.g., session length or administrative rules), and even modify the number of Supreme Court justices, as it has done countless times since the beginning of the republic. |

Modern Relevance

The Federalist principles remain profoundly relevant in contemporary debates about governance, individual liberty, and the role of government:

- Federalism and Decentralization: Debates over federal versus state authority—such as those surrounding healthcare, education, or environmental policy—echo the Federalists’ vision of dual sovereignty. For example, disputes over federal mandates versus state autonomy in the U.S. reflect the tension between unity and local control.

- Judicial Review: Hamilton’s defense of judicial independence in Federalist No. 78 resonates in modern discussions about the judiciary’s role in checking legislative and executive power. Landmark U.S. Supreme Court cases, such as Marbury v. Madison (1803), which established judicial review, and recent rulings on constitutional issues, underscore the enduring importance of an independent judiciary.

- Factions and Polarization: Madison’s warnings about factions are strikingly relevant in today’s polarized political climate. The rise of partisan divisions, interest groups, and social media echo chambers mirrors the factionalism Madison sought to mitigate. His advocacy for a large republic and representative government offers insights into managing modern political divisions.

- Liberty versus Security: The Federalists’ balance between a strong government and individual liberty informs contemporary debates over national security, surveillance, and civil liberties. Issues like government data collection or emergency powers during crises reflect the ongoing challenge of maintaining freedom while ensuring stability.

- Global Influence: The Federalist model of federalism, separation of powers, and constitutionalism has influenced democratic systems worldwide. Countries like Canada, Australia, and Germany have adopted federal structures, while constitutional courts in nations like South Africa and India draw on the principle of judicial review.

| National Urban Development Policy and Brazilian Federalism When reviewing the process of “Audit on the Formulation, Implementation, and Monitoring of Results of the Public Policy to Support the National Urban Development Policy” (TC 016.327/2017-9), the Federal Court of Auditors issued Ruling 2359/2018-Plenary, whose preceding report contains, among other things, the following policy analyses: III.1.1. The Union is unaware of the problem to which it intends to contribute, and there is no evidence that it has any relevant contribution, other than financial, to solving the problem. A diagnosis of the problem situation was not carried out to determine its nature, scope, and dimension. It was also found that the public policy lacks justification; that is, the reasons leading the Union to intervene in municipal urban paving are unclear, and, furthermore, the public policy was not formulated based on evidence. (…) 51. However, the central question that should be answered is whether the Union is the most appropriate sphere of government to conduct such analyses, whether due to the high difficulty and cost that a central entity will have to maintain up-to-date information on numerous local realities; or due to the dynamic nature of municipal paving; or because the matter falls within the jurisdiction of municipalities; or because of the proximity of municipalities to the problem, the allocation of resources, and the target audience; or because public policy contributes to the consolidation of the fiscal imbalance of the federative pact (rather than seeking to resolve it); or because of the high transaction costs created by the model. (…) Since the Union is the central entity of a country of continental proportions like Brazil, it seems more coherent to expect action that effectively qualifies the allocation of municipal resources, strengthening the effectiveness of the municipality’s work in the area of planning and execution of urban infrastructure works. On the other hand, it seems to make little sense (and no reasonable justifications were presented) for the Federal Government to allocate resources and control routine municipal paving actions, precisely what has been done with Action 1D73. III.1.3. There is no evidence that Action 1D73 is the best way for the Federal Government to contribute to solving the municipal paving problem. In addition to the fact that the public policy was not formulated based on an appropriate, evidence-based diagnosis and lacks valid objectives, different alternative formats for the public policy were not evaluated, with a view to selecting the most cost-effective one and, consequently, the one that delivers the intended result at the lowest cost to society. (…) It is noteworthy that no reflection or analysis was found on aspects of the Federative Pact regarding Action 1D73 and its transfer model, which presented the reasons for the Union’s intervention in specific urban planning elements, given that it is the municipal authority to implement public urban development policies (art. 182, caput, Federal Constitution). The fact that the Union is permanently supporting actions of local interest, due to a hypothetical chronic and widespread lack of resources, suggests an imbalance in the Federative Pact. This aspect should be considered when formulating public policy alternatives. (…) |

Challenges to Federalist Principles

While the Federalist framework has proven resilient, it faces challenges in the modern era:

- Centralization of Power: The growth of the federal government’s role in areas like welfare, regulation, and national security has sparked debates about whether it aligns with the Federalists’ vision of limited government. Programs like Social Security or the Affordable Care Act exceed the original constitutional scope..

- Erosion of Civic Virtue: Adams’ emphasis on a moral and religious populace raises questions about whether modern societies retain the ethical foundation needed for self-governance. Declining trust in institutions, political apathy, and cultural fragmentation challenge the Federalists’ assumption of a virtuous citizenry.

- Globalization and Sovereignty: In an interconnected world, the Federalists’ focus on national unity and sovereignty faces new complexities. International agreements, global economic pressures, and transnational issues require cooperation that may conflict with strict federalist principles.

| Roosevelt and the 10th Amendment. According to the Center for the Study of Federalism, recounting the history of American federalism: “TENTH AMENDMENT The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people. (…) This general theme, finding the Supreme Court striking down a variety of federal legislation under the authority of the Tenth Amendment, would continue until 1937. The reasons for the shift in interpretation regarding the Tenth Amendment are many, but the main trigger was more political than legal. After several major New Deal laws had been held unconstitutional, President Franklin D. Roosevelt came to believe that something had to be done about the Court in order to save the New Deal. Following his reelection in 1936, President Roosevelt proposed changes to the makeup of the federal judiciary. Making the argument that the courts were overburdened and filled with many infirm judges, Roosevelt proposed that for every judge over the age of 70, the president should be entitled to appoint one additional judge to the court where the senior judge was commissioned (up to a maximum of fifteen members for the U.S. Supreme Court). At the time of his proposal, six of the nine Supreme Court justices were over the age of 70. Accordingly, had this plan been approved, President Roosevelt would have been able to add six new justices to the Supreme Court and, in doing so, would have been able to select individuals who shared his views regarding federal power under the Tenth Amendment. The “court-packing plan,” as this became known, was never enacted. However, the threat to the integrity of the judiciary did produce the results Roosevelt had been seeking. In a virtually unbroken line of cases, beginning in 1937 and lasting until 1995, the interpretation of the Tenth Amendment and the scope of federal power under the Commerce Clause changed dramatically. While most pre-1937 decisions had used the Tenth Amendment to strictly limit the reach of the federal government, beginning with National Labor Relations Board v. Jones and Laughlin Steel Corporation (1937), the scope of federal power was allowed to increase exponentially while at the same time the Tenth Amendment was relegated to practical insignificance.” |

Conclusion

The Federalist Papers remain a cornerstone of political thought, articulating a vision of governance that balances strength with restraint, unity with diversity, and liberty with order. Rooted in classical liberalism, the Federalists’ principles of natural rights, limited government, separation of powers, and federalism shaped the United States’ foundation and continue to influence democratic systems globally. Their insights into human nature, institutional design, and civic virtue offer timeless lessons for navigating the challenges of governance in a complex and evolving world. As debates over individual freedom, government authority, and societal values persist, the Federalists’ call for a government “by reflection and choice” remains a guiding light for those seeking to preserve liberty and justice.

Selected text

The Federalist Papers : No. 10

The same object continued

The Union as a Safeguard Against Domestic Faction and Insurrection

From the New York Packet. Friday, November 23, 1787.

MADISON

To the People of the State of New York:

AMONG the numerous advantages promised by a wellconstructed Union, none deserves to be more accurately developed than its tendency to break and control the violence of faction. The friend of popular governments never finds himself so much alarmed for their character and fate, as when he contemplates their propensity to this dangerous vice. He will not fail, therefore, to set a due value on any plan which, without violating the principles to which he is attached, provides a proper cure for it. The instability, injustice, and confusion introduced into the public councils, have, in truth, been the mortal diseases under which popular governments have everywhere perished; as they continue to be the favorite and fruitful topics from which the adversaries to liberty derive their most specious declamations. The valuable improvements made by the American constitutions on the popular models, both ancient and modern, cannot certainly be too much admired; but it would be an unwarrantable partiality, to contend that they have as effectually obviated the danger on this side, as was wished and expected. Complaints are everywhere heard from our most considerate and virtuous citizens, equally the friends of public and private faith, and of public and personal liberty, that our governments are too unstable, that the public good is disregarded in the conflicts of rival parties, and that measures are too often decided, not according to the rules of justice and the rights of the minor party, but by the superior force of an interested and overbearing majority. However anxiously we may wish that these complaints had no foundation, the evidence, of known facts will not permit us to deny that they are in some degree true. It will be found, indeed, on a candid review of our situation, that some of the distresses under which we labor have been erroneously charged on the operation of our governments; but it will be found, at the same time, that other causes will not alone account for many of our heaviest misfortunes; and, particularly, for that prevailing and increasing distrust of public engagements, and alarm for private rights, which are echoed from one end of the continent to the other. These must be chiefly, if not wholly, effects of the unsteadiness and injustice with which a factious spirit has tainted our public administrations.

By a faction, I understand a number of citizens, whether amounting to a majority or a minority of the whole, who are united and actuated by some common impulse of passion, or of interest, adversed to the rights of other citizens, or to the permanent and aggregate interests of the community.

There are two methods of curing the mischiefs of faction: the one, by removing its causes; the other, by controlling its effects.

There are again two methods of removing the causes of faction: the one, by destroying the liberty which is essential to its existence; the other, by giving to every citizen the same opinions, the same passions, and the same interests.

It could never be more truly said than of the first remedy, that it was worse than the disease. Liberty is to faction what air is to fire, an aliment without which it instantly expires. But it could not be less folly to abolish liberty, which is essential to political life, because it nourishes faction, than it would be to wish the annihilation of air, which is essential to animal life, because it imparts to fire its destructive agency.

The second expedient is as impracticable as the first would be unwise. As long as the reason of man continues fallible, and he is at liberty to exercise it, different opinions will be formed. As long as the connection subsists between his reason and his self-love, his opinions and his passions will have a reciprocal influence on each other; and the former will be objects to which the latter will attach themselves. The diversity in the faculties of men, from which the rights of property originate, is not less an insuperable obstacle to a uniformity of interests. The protection of these faculties is the first object of government. From the protection of different and unequal faculties of acquiring property, the possession of different degrees and kinds of property immediately results; and from the influence of these on the sentiments and views of the respective proprietors, ensues a division of the society into different interests and parties.

The latent causes of faction are thus sown in the nature of man; and we see them everywhere brought into different degrees of activity, according to the different circumstances of civil society. A zeal for different opinions concerning religion, concerning government, and many other points, as well of speculation as of practice; an attachment to different leaders ambitiously contending for pre-eminence and power; or to persons of other descriptions whose fortunes have been interesting to the human passions, have, in turn, divided mankind into parties, inflamed them with mutual animosity, and rendered them much more disposed to vex and oppress each other than to co-operate for their common good. So strong is this propensity of mankind to fall into mutual animosities, that where no substantial occasion presents itself, the most frivolous and fanciful distinctions have been sufficient to kindle their unfriendly passions and excite their most violent conflicts. But the most common and durable source of factions has been the various and unequal distribution of property. Those who hold and those who are without property have ever formed distinct interests in society. Those who are creditors, and those who are debtors, fall under a like discrimination. A landed interest, a manufacturing interest, a mercantile interest, a moneyed interest, with many lesser interests, grow up of necessity in civilized nations, and divide them into different classes, actuated by different sentiments and views. The regulation of these various and interfering interests forms the principal task of modern legislation, and involves the spirit of party and faction in the necessary and ordinary operations of the government.

No man is allowed to be a judge in his own cause, because his interest would certainly bias his judgment, and, not improbably, corrupt his integrity. With equal, nay with greater reason, a body of men are unfit to be both judges and parties at the same time; yet what are many of the most important acts of legislation, but so many judicial determinations, not indeed concerning the rights of single persons, but concerning the rights of large bodies of citizens? And what are the different classes of legislators but advocates and parties to the causes which they determine? Is a law proposed concerning private debts? It is a question to which the creditors are parties on one side and the debtors on the other. Justice ought to hold the balance between them. Yet the parties are, and must be, themselves the judges; and the most numerous party, or, in other words, the most powerful faction must be expected to prevail. Shall domestic manufactures be encouraged, and in what degree, by restrictions on foreign manufactures? are questions which would be differently decided by the landed and the manufacturing classes, and probably by neither with a sole regard to justice and the public good. The apportionment of taxes on the various descriptions of property is an act which seems to require the most exact impartiality; yet there is, perhaps, no legislative act in which greater opportunity and temptation are given to a predominant party to trample on the rules of justice. Every shilling with which they overburden the inferior number, is a shilling saved to their own pockets.

It is in vain to say that enlightened statesmen will be able to adjust these clashing interests, and render them all subservient to the public good. Enlightened statesmen will not always be at the helm. Nor, in many cases, can such an adjustment be made at all without taking into view indirect and remote considerations, which will rarely prevail over the immediate interest which one party may find in disregarding the rights of another or the good of the whole.

The inference to which we are brought is, that the CAUSES of faction cannot be removed, and that relief is only to be sought in the means of controlling its EFFECTS.

If a faction consists of less than a majority, relief is supplied by the republican principle, which enables the majority to defeat its sinister views by regular vote. It may clog the administration, it may convulse the society; but it will be unable to execute and mask its violence under the forms of the Constitution. When a majority is included in a faction, the form of popular government, on the other hand, enables it to sacrifice to its ruling passion or interest both the public good and the rights of other citizens. To secure the public good and private rights against the danger of such a faction, and at the same time to preserve the spirit and the form of popular government, is then the great object to which our inquiries are directed. Let me add that it is the great desideratum by which this form of government can be rescued from the opprobrium under which it has so long labored, and be recommended to the esteem and adoption of mankind.

By what means is this object attainable? Evidently by one of two only. Either the existence of the same passion or interest in a majority at the same time must be prevented, or the majority, having such coexistent passion or interest, must be rendered, by their number and local situation, unable to concert and carry into effect schemes of oppression. If the impulse and the opportunity be suffered to coincide, we well know that neither moral nor religious motives can be relied on as an adequate control. They are not found to be such on the injustice and violence of individuals, and lose their efficacy in proportion to the number combined together, that is, in proportion as their efficacy becomes needful.

From this view of the subject it may be concluded that a pure democracy, by which I mean a society consisting of a small number of citizens, who assemble and administer the government in person, can admit of no cure for the mischiefs of faction. A common passion or interest will, in almost every case, be felt by a majority of the whole; a communication and concert result from the form of government itself; and there is nothing to check the inducements to sacrifice the weaker party or an obnoxious individual. Hence it is that such democracies have ever been spectacles of turbulence and contention; have ever been found incompatible with personal security or the rights of property; and have in general been as short in their lives as they have been violent in their deaths. Theoretic politicians, who have patronized this species of government, have erroneously supposed that by reducing mankind to a perfect equality in their political rights, they would, at the same time, be perfectly equalized and assimilated in their possessions, their opinions, and their passions.

A republic, by which I mean a government in which the scheme of representation takes place, opens a different prospect, and promises the cure for which we are seeking. Let us examine the points in which it varies from pure democracy, and we shall comprehend both the nature of the cure and the efficacy which it must derive from the Union.

The two great points of difference between a democracy and a republic are: first, the delegation of the government, in the latter, to a small number of citizens elected by the rest; secondly, the greater number of citizens, and greater sphere of country, over which the latter may be extended.

The effect of the first difference is, on the one hand, to refine and enlarge the public views, by passing them through the medium of a chosen body of citizens, whose wisdom may best discern the true interest of their country, and whose patriotism and love of justice will be least likely to sacrifice it to temporary or partial considerations. Under such a regulation, it may well happen that the public voice, pronounced by the representatives of the people, will be more consonant to the public good than if pronounced by the people themselves, convened for the purpose. On the other hand, the effect may be inverted. Men of factious tempers, of local prejudices, or of sinister designs, may, by intrigue, by corruption, or by other means, first obtain the suffrages, and then betray the interests, of the people. The question resulting is, whether small or extensive republics are more favorable to the election of proper guardians of the public weal; and it is clearly decided in favor of the latter by two obvious considerations:

In the first place, it is to be remarked that, however small the republic may be, the representatives must be raised to a certain number, in order to guard against the cabals of a few; and that, however large it may be, they must be limited to a certain number, in order to guard against the confusion of a multitude. Hence, the number of representatives in the two cases not being in proportion to that of the two constituents, and being proportionally greater in the small republic, it follows that, if the proportion of fit characters be not less in the large than in the small republic, the former will present a greater option, and consequently a greater probability of a fit choice.

In the next place, as each representative will be chosen by a greater number of citizens in the large than in the small republic, it will be more difficult for unworthy candidates to practice with success the vicious arts by which elections are too often carried; and the suffrages of the people being more free, will be more likely to centre in men who possess the most attractive merit and the most diffusive and established characters.

It must be confessed that in this, as in most other cases, there is a mean, on both sides of which inconveniences will be found to lie. By enlarging too much the number of electors, you render the representatives too little acquainted with all their local circumstances and lesser interests; as by reducing it too much, you render him unduly attached to these, and too little fit to comprehend and pursue great and national objects. The federal Constitution forms a happy combination in this respect; the great and aggregate interests being referred to the national, the local and particular to the State legislatures.

The other point of difference is, the greater number of citizens and extent of territory which may be brought within the compass of republican than of democratic government; and it is this circumstance principally which renders factious combinations less to be dreaded in the former than in the latter. The smaller the society, the fewer probably will be the distinct parties and interests composing it; the fewer the distinct parties and interests, the more frequently will a majority be found of the same party; and the smaller the number of individuals composing a majority, and the smaller the compass within which they are placed, the more easily will they concert and execute their plans of oppression. Extend the sphere, and you take in a greater variety of parties and interests; you make it less probable that a majority of the whole will have a common motive to invade the rights of other citizens; or if such a common motive exists, it will be more difficult for all who feel it to discover their own strength, and to act in unison with each other. Besides other impediments, it may be remarked that, where there is a consciousness of unjust or dishonorable purposes, communication is always checked by distrust in proportion to the number whose concurrence is necessary.

Hence, it clearly appears, that the same advantage which a republic has over a democracy, in controlling the effects of faction, is enjoyed by a large over a small republic,–is enjoyed by the Union over the States composing it. Does the advantage consist in the substitution of representatives whose enlightened views and virtuous sentiments render them superior to local prejudices and schemes of injustice? It will not be denied that the representation of the Union will be most likely to possess these requisite endowments. Does it consist in the greater security afforded by a greater variety of parties, against the event of any one party being able to outnumber and oppress the rest? In an equal degree does the increased variety of parties comprised within the Union, increase this security. Does it, in fine, consist in the greater obstacles opposed to the concert and accomplishment of the secret wishes of an unjust and interested majority? Here, again, the extent of the Union gives it the most palpable advantage.

The influence of factious leaders may kindle a flame within their particular States, but will be unable to spread a general conflagration through the other States. A religious sect may degenerate into a political faction in a part of the Confederacy; but the variety of sects dispersed over the entire face of it must secure the national councils against any danger from that source. A rage for paper money, for an abolition of debts, for an equal division of property, or for any other improper or wicked project, will be less apt to pervade the whole body of the Union than a particular member of it; in the same proportion as such a malady is more likely to taint a particular county or district, than an entire State.

In the extent and proper structure of the Union, therefore, we behold a republican remedy for the diseases most incident to republican government. And according to the degree of pleasure and pride we feel in being republicans, ought to be our zeal in cherishing the spirit and supporting the character of Federalists.

PUBLIUS.

Reflection Questions

1. In what ways do the Federalist Papers address concerns about the excessive power of the central government?

2. How can factions be controlled in a reality like Brazil’s?

3. How can the facts described in the box about “Funasa and Brazilian federalism” be understood in light of the ideas in Federalist Paper No. 10?

4. Brazil is experiencing a dictatorship of the judiciary (especially Supreme Court Justice Alexandre de Moraes), in collusion with the head of the Executive Branch (Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva). If you were responsible for a constitutional reform, what changes would you propose to fix the Brazilian Constitution?

5. Reflect on Madison’s analysis in Federalist No. 10 of factions as inevitable due to human diversity— in what ways might this explain the rise of identity politics and partisan divisions in today’s polarized political landscapes?

6. How does the conflict between Hamilton (broad interpretation) and Madison/Jefferson (narrow interpretation) of the Constitution relate to contemporary debates about originalism versus living constitutionalism?

7. What insights does Madison’s warning that accepting Hamilton’s view would make the government “no longer limited with enumerated powers, but indefinite subject to particular exceptions” offer for concerns about contemporary federal expansion?

8. How can the Federalists’ warnings about centralized tyranny guide reflections on the expansion of federal powers in economic regulation today, particularly in responses to global challenges like climate change or economic inequality?