Historical and Philosophical Context

Frédéric Bastiat (1801–1850) wrote during a period of intense political and economic turmoil in France, marked by the Revolution of 1848 and the rise of socialist ideas led by figures such as Louis Blanc. As a member of the French National Assembly, Bastiat advocated free trade and opposed protectionist policies, inspired by the ideas of Adam Smith. His work reflects classical liberalism, emphasizing individual freedom and criticizing state intervention, in a context of debates about redistribution and economic control.

Bastiat is known for his accessible style, using parables and satire, such as the famous “Candlemakers’ Petition” against sunlight, to make economic ideas understandable to the public, amplifying their impact. His ideas influenced later thinkers such as Ludwig von Mises and Friedrich Hayek and remain relevant in public policy discussions.

Figure 17: Lithograph by Frédéric Bastiat.

Author: Émile Desmaisons.

Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Bastiat.jpg

Bastiat’s Core Ideas

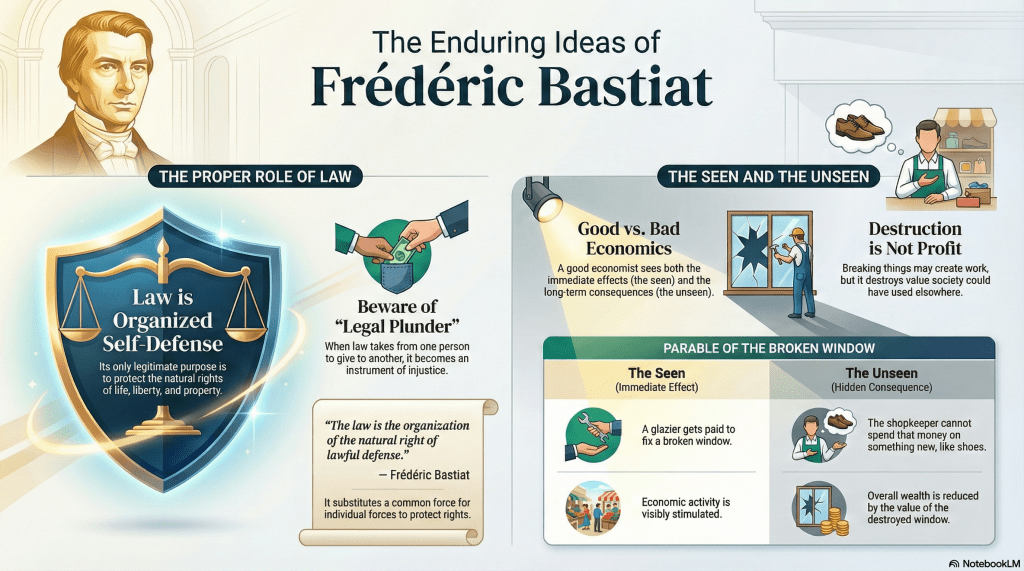

Bastiat presents two main contributions: his definition of law and his analysis of the visible and invisible effects of public policies.

The Nature of Law

In The Law, Bastiat argues that law exists to protect the natural rights of individuals, which he defines as life, liberty, and property, echoing John Locke. He writes:

“Law is the organization of the natural right of legitimate defense. It is the substitution of a common force for individual forces. And this common force must do only what individual forces have a natural and legitimate right to do: protect persons, liberties, and properties” (The Law, Section II).

For Bastiat, law should be limited to guaranteeing these rights, ensuring that individuals can pursue their interests without harming others. He vehemently criticizes “legal plunder,” where the law is perverted to take from some and give to others, whether through redistribution, protectionism, or subsidies. He warns:

“When a portion of wealth is transferred from the person who possesses it—without his consent and without compensation…to another who does not possess it, then I say that this is plunder” (The Law, Section V).

This criticism targets socialist policies that redistribute wealth, which Bastiat sees as a violation of justice and morality, replacing voluntary exchange with coercion.

The Seen and the Unseen

In his essay “The Seen and the Unseen,” Bastiat introduces a powerful analytical tool: the distinction between the immediate, visible effects of a policy (the “seen”) and its hidden, long-term consequences (the “unseen”). He uses the parable of the broken window to illustrate this. If a shopkeeper’s window is broken, the immediate (seen) effect is economic activity—the glazier is paid to repair it. However, the invisible cost is what the shopkeeper could have done with that money, such as buying new shoes, which would have stimulated other economic activity. Bastiat writes:

“It is not seen that, since our shopkeeper spent six francs on one thing, he cannot spend them on another. It is not seen that, if he had not had a window to replace, he might have replaced his old shoes” (“What is Seen and What is Unseen,” Chapter I).

This framework criticizes policies such as tariffs, subsidies, or public works, which may appear beneficial but often divert resources from more productive uses, reducing overall wealth. The idea emphasizes the importance of considering opportunity costs in policymaking, a principle that resonates with Adam Smith’s advocacy of free markets and minimal government intervention.

| Some lessons from Bastiat for public policy makers The evaluation of public policies should consider opportunity costs, inefficiencies of state action, and unintended consequences of the policy. There are unintended consequences of public policies that will only be known in the long term (and therefore cannot be identified during policy formulation). Thus, in the evaluation of public policies, it must be considered that there is an optimism bias that must be compensated for. |

Limited Government Vision

Bastiat’s liberalism is uncompromising in its defense of individual liberty and skepticism of excessive government. He argues that governments should limit themselves to protecting rights, not engineering society or redistributing wealth. Unlike Montesquieu, who emphasized contextual laws, or Smith, who allowed some public goods, Bastiat is more radical in his minimalism, viewing most state interventions as distortions of the natural economic and social order. However, he recognizes the need for government to maintain order, aligning with the federalist recognition of human imperfection. His focus on voluntary exchange and property rights builds on Locke and Smith, making him a bridge between philosophical and economic liberalism.

| The Most Important Lesson of Economics (That Socialists Stubbornly Refuse to Learn) Henry Stuart Hazlitt (1894-1993) was an American journalist, economist, and philosopher, and the well-known author of the book “Economics in One Lesson,” which reads: “In this respect, then, the whole of economics can be reduced to a single lesson, and that lesson can be reduced to a single sentence. The art of economics consists in looking not only at the immediate but also at the long-term effects of any act or policy; in tracing the consequences of that policy not only for one group but for all groups.“ |

Relationship to the Circular Diagram of Political Mindsets

In the circular diagram, Bastiat is a quintessential classical liberal thinker, advocating individual liberty, free markets, and limited government. His ideas connect with adjacent groups and contrast sharply with their opposites:

Democratic Leftists: Bastiat shares with democratic socialists a concern for individual dignity, but diverges sharply on economic intervention. While social democrats, such as those in post-war Sweden, advocate welfare states to address inequality, Bastiat’s critique of legal plunder condemns such redistribution as coercive, favoring voluntary charity.

Moderate Conservatives: Bastiat’s respect for property and social order aligns with moderate conservatives who value stability and markets, such as those influenced by Edmund Burke or Margaret Thatcher. However, his rejection of state-backed privileges, such as mercantilist monopolies, distinguishes him from conservatives who tolerate economic controls for traditionalist ends.

Opposition to Radical Statists and Radical Leftists: Bastiat’s fierce opposition to legal plunder and centralized control puts him in direct conflict with radical statists, such as those in Mussolini’s fascist Italy or Stalin’s Soviet Union, who prioritize state power over individual rights. Likewise, he rejects the revolutionary collectivism of radical leftists like Marx, whose vision of state-controlled economies he sees as a path to tyranny.

Modern Relevance

Bastiat’s ideas remain central to debates about the role of government in the economy. Classical liberals like Milton Friedman and members of the libertarian movement like Ron Paul draw on his principles to advocate for deregulation, free trade, and tax cuts. His “seen and unseen” framework is used to criticize policies like minimum wage laws, corporate bailouts, or green subsidies, which may have visible benefits but hidden costs, such as job losses or market distortions.

| Miley and Bastiat Javier Gerardo Milei (1970), President of Argentina, at the inauguration of the Portal del Cielo Church in Chaco, stated: “In recent decades, the left has imposed a single discourse on justice, understood exclusively in distributive terms. But this is not the true meaning of justice, because it is intrinsically unjust. Because to give to some, one must take from others, and because, as we learned the hard way in Argentina, those who distribute get the best part. But fortunately, they are beginning to fall into the trap. The true meaning of justice is that what one has in life will be based on merit and the tenacity one employs in the pursuit of one’s goals. Justice is a matter of retribution, that is, that each person receives what is due to them. They often repeat that no one is saved and accuse us of being individualists. But the reality is that capitalism fosters the only truly genuine communities, where individuals associate voluntarily. In them, one must satisfy one’s neighbor with goods and services that one does not wants, cannot, or does not know how to provide for the betterment of one’s own life. This is true organized community, not the leftist justification for forced collectivization. In fact, the capitalist system is not only the only one that generates efficiency, but also promotes peace. There is a very notable quote from Bastiat: “Where commerce enters, bullets do not enter.” Furthermore, commerce creates interdependence and forces us to live together in peace, and that is wonderful. But obviously, what is the left doing? It reverses everything.” (https://www.casarosada.gob.ar/slider-principal/51020-palabras-del-presidente-de-la-nacion-javier-milei-en-la-inauguracion-de-la-iglesia-portal-del-cielo-en-chaco) |

Bastiat’s clarity in defending liberty and exposing the unintended consequences of policies makes his work a vital tool for analyzing government action today. His emphasis on the law as a protector of rights challenges policymakers to prioritize liberty over coercion.

Summary Table of Bastiat’s Ideas

| Aspect | Description | Connection with Classical Liberalism |

| Definition of Law | Protects life, liberty, and property, opposes “legal plunder” | Based on Locke’s natural rights |

| The Seen and the Unseen | Analyzes hidden costs of policies, as in the parable of the broken window | Criticizes state interventions, echoing Smith |

| View of Government | Minimalist, limited to protecting rights, rejects redistribution | Aligns with Hayek and Friedman |

| Historical Context | Wrote against socialism in 19th-century France | Reflects debates on the free market |

Conclusion

Frédéric Bastiat’s “The Law” and “That Which is Seen, and That Which is Not Seen” offer a powerful defense of individual liberty and a critique of government overreach. Defining law as the protector of natural rights and exposing the hidden costs of public policies, Bastiat reinforces the classical liberal mindset in the circular diagram, connecting philosophical and economic arguments for liberty while opposing collectivist and authoritarian ideologies. His ideas, born in 19th-century France, continue to illuminate debates about the role of government, reminding us that true justice lies in protecting individual rights and considering the unseen consequences of state action.

Textos selecionados

Bastiat, Frédéric. The Law. Ludwig von Mises Institute, 2007.

(…)

We hold from God the gift that, as far as we are concerned, contains all others, Life—physical, intellectual, and moral life

(…)

It is not because men have made laws, that personality, liberty, and property exist. On the contrary, it is

because personality, liberty, and property exist beforehand, that men make laws. What, then, is law? As I have said elsewhere, it is the collective organization of the individual right to lawful defense.

Nature, or rather God, has bestowed upon every one of us the right to defend his person, his liberty, and his property, since these are the three constituent or preserving elements of life; elements, each of which is rendered complete by the others, and that cannot be understood without them. For what are our faculties, but the extension of our personality? and what is property, but an extension of our faculties?

If every man has the right of defending, even by force, his person, his liberty, and his property, a number of men have the right to combine together to extend, to organize a common force to provide regularly for this defense.

Collective right, then, has its principle, its reason for existing, its lawfulness, in individual right; and the common force cannot rationally have any other end, or any other mission, than that of the isolated forces for which it is substituted. Thus, as the force of an individual cannot lawfully touch the person, the liberty, or the property of another individual—for the same reason, the common force cannot lawfully be used to destroy the person, the liberty, or the property of individuals or of classes.

For this perversion of force would be, in one case as in the other, in contradiction to our premises. For who will dare to say that force has been given to us, not to defend our rights, but to annihilate the equal rights of our brethren? And if this be not true of every individual force, acting independently, how can it be true of the collective force, which is only the organized union of isolated forces?

Nothing, therefore, can be more evident than this: The law is the organization of the natural right of lawful defense; it is the substitution of collective for individual forces, for the purpose of acting in the sphere in which they have a right to act, of doing what they have a right to do, to secure persons, liberties, and properties, and to maintain each in its right, so as to cause justice to reign over all.

(…)

Unhappily, law is by no means confined to its own sphere. Nor is it merely in some ambiguous and debatable views that it has left its proper sphere. It has done more than this. It has acted in direct opposition to its proper end; it has destroyed its own object; it has been employed in annihilating that justice which it ought to have established, in effacing amongst Rights, that limit which it was its true mission to respect; it has placed the collective force in the service of those who wish to traffic, without risk and without scruple, in the persons, the liberty, and the property of others; it has converted plunder into a right, that it may protect it, and lawful defense into a crime, that it may punish it.

How has this perversion of law been accomplished?

And what has resulted from it?

The law has been perverted through the influence of two very different causes—naked greed and misconceived philanthropy.

Let us speak of the former. Self-preservation and development is the common aspiration of all men, in such a way that if every one enjoyed the free exercise of his faculties and the free disposition of their fruits, social progress would be incessant, uninterrupted, inevitable.

But there is also another disposition which is common to them. This is to live and to develop, when they can, at the expense of one another. This is no rash imputation, emanating from a gloomy, uncharitable spirit. History bears witness to the truth of it, by the incessant wars, the migrations of races, sectarian oppressions, the universality of slavery, the frauds in trade, and the monopolies with

which its annals abound. This fatal disposition has its origin in the very constitution of man—in that primitive, and universal, and invincible sentiment that urges it towards its well-being, and makes it seek to escape pain.

(…)

That Which is Seen, and That Which is Not Seen

Introduction

In the department of economy, an act, a habit, an institution, a law, gives birth not only to an effect, but to a series of effects. Of these effects, the first only is immediate; it manifests itself simultaneously with its cause — it is seen. The others unfold in succession — they are not seen: it is well for us, if they are foreseen. Between a good and a bad economist this constitutes the whole difference — the one takes account of the visible effect; the other takes account both of the effects which are seen, and also of those which it is necessary to foresee. Now this difference is enormous, for it almost always happens that when the immediate consequence is favourable, the ultimate consequences are fatal, and the converse. Hence it follows that the bad economist pursues a small present good, which will be followed by a great evil to come, while the true economist pursues a great good to come, — at the risk of a small present evil.

In fact, it is the same in the science of health, arts, and in that of morals. It often happens, that the sweeter the first fruit of a habit is, the more bitter are the consequences. Take, for example, debauchery, idleness, prodigality. When, therefore, a man absorbed in the effect which is seen has not yet learned to discern those which are not seen, he gives way to fatal habits, not only by inclination, but by calculation.

(…>

I. The Broken Window

Have you ever witnessed the anger of the good shopkeeper, James B., when his careless son happened to break a square of glass? If you have been present at such a scene, you will most assuredly bear witness to the fact, that every one of the spectators, were there even thirty of them, by common consent apparently, offered the unfortunate owner this invariable consolation — “It is an ill wind that blows nobody good. Everybody must live, and what would become of the glaziers if panes of glass were never broken?”

Now, this form of condolence contains an entire theory, which it will be well to show up in this simple case, seeing that it is precisely the same as that which, unhappily, regulates the greater part of our economical institutions.

Suppose it cost six francs to repair the damage, and you say that the accident brings six francs to the glazier’s trade — that it encourages that trade to the amount of six francs — I grant it; I have not a word to say against it; you reason justly. The glazier comes, performs his task, receives his six francs, rubs his hands, and, in his heart, blesses the careless child. All this is that which is seen.

But if, on the other hand, you come to the conclusion, as is too often the case, that it is a good thing to break windows, that it causes money to circulate, and that the encouragement of industry in general will be the result of it, you will oblige me to call out, “Stop there! your theory is confined to that which is seen; it takes no account of that which is not seen.”

It is not seen that as our shopkeeper has spent six francs upon one thing, he cannot spend them upon another. It is not seen that if he had not had a window to replace, he would, perhaps, have replaced his old shoes, or added another book to his library. In short, he would have employed his six francs in some way, which this accident has prevented.

(…)

Now, as James B. forms a part of society, we must come to the conclusion, that, taking it altogether, and making an estimate of its enjoyments and its labours, it has lost the value of the broken window.

When we arrive at this unexpected conclusion: “Society loses the value of things which are uselessly destroyed;” and we must assent to a maxim which will make the hair of protectionists stand on end — To break, to spoil, to waste, is not to encourage national labour; or, more briefly, “destruction is not profit.”

(…)

Questions for Reflection

1. Does it make sense for the government to spend resources taken from citizens through taxes on unnecessary projects under the argument of creating jobs and increasing GDP?

2. How does Bastiat’s definition of law as the protector of natural rights—life, liberty, and property—challenge contemporary views on expansive government roles in areas like healthcare or education, where state intervention is often justified as promoting social equity?

3. Reflect on the concept of “legal plunder” in Bastiat’s “The Law”—in what ways might this critique apply to modern progressive taxation systems or wealth redistribution policies in countries like the United States or France?

4. Discuss the parable of the broken window and its illustration of seen versus unseen effects; how could this framework inform evaluations of economic stimulus packages during crises, such as those implemented in response to the 2008 financial meltdown or the COVID-19 pandemic?

5. Reflect on Javier Milei’s reference to Bastiat in critiquing distributive justice—how might this perspective influence ongoing reforms in Argentina or inspire libertarian movements in other nations facing fiscal deficits?

6. How does Bastiat’s emphasis on voluntary exchange over coercion in economic interactions critique contemporary corporate bailouts or green energy subsidies, which often create unseen market distortions?

7. In what ways does the distinction between seen benefits (e.g., job creation from public works) and unseen costs (e.g., opportunity costs of taxation) apply to modern infrastructure bills, like those in the U.S. aimed at climate resilience?

8. How does Bastia’s concern that the expansion of laws turns everyone into a potential criminal—”when law and morality contradict each other, citizens have the cruel alternative of losing their moral sense or respect for the law”—apply to contemporary phenomena of excessive criminalization and the police state?

Leave a comment