Conceptualizing Socialism: Collectivism and/or Egalitarianism

Socialism is usually conceptualized as the socioeconomic system in which the means of production are owned or regulated by the state or the community as a whole. In this sense, it contrasts with capitalism, in which the means of production are privately organized (that is, they are owned by ordinary citizens).

However, authors usually classified as socialists do not always focus on state or collective ownership of the means of production. Often, what characterizes their actions is the distributivism of goods and rights (taking goods and rights from some to give to others, often to the state – as usually occurs with market regulation – under the argument of representing the interest of society).

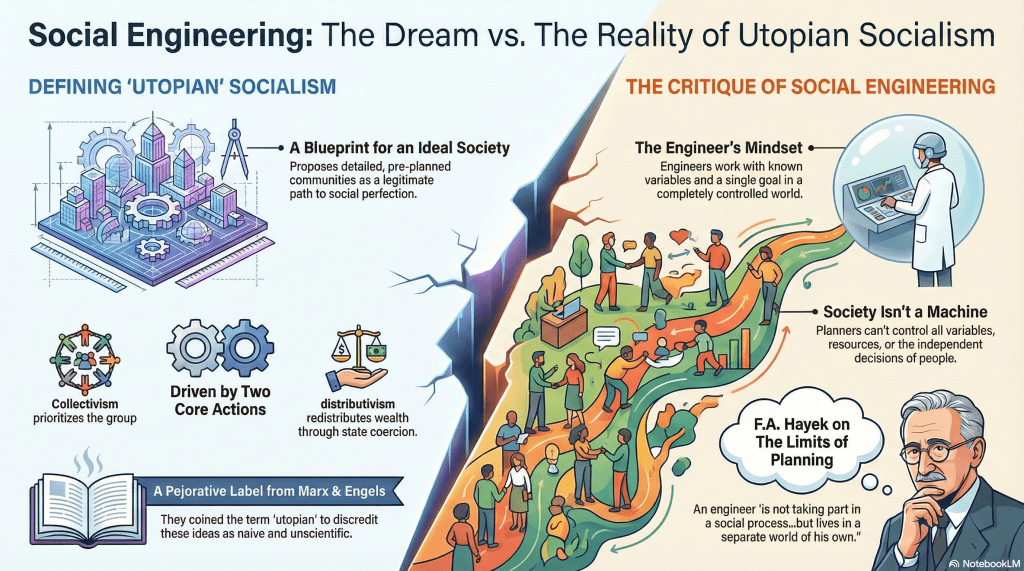

Thus, socialism moves through two basic groups of actions:

Collectivism refers to the prioritization of the group or society over individual interests, suggesting that resources, production, and decision-making should be collectively owned or controlled. This is evident in the communal ownership proposed by utopian socialists, emphasizing shared responsibility and mutual aid.

Distributivism is the removal of goods and rights from individuals or groups of individuals in society to deliver these goods and rights to other individuals or groups of individuals through state action (via coercion).

The claim used to justify their actions is egalitarianism, that is, the belief that their actions will produce greater economic equality and, with that, a better society. This belief is not based on robust evidence; on the contrary, historical evidence shows that both actions impoverish society, if not produce sick people and a sick society. This, however, is not an obstacle for socialists, whether due to their eminently utopian nature or their nihilistic nature.

| Ayn Rand and her “Atlas Shrugged” The author who possibly most prominently defends the principle that no one can live based on the labor of others, and who harshly criticizes any system that allows this, is Ayn Rand. Alice O’Connor (born Alisa Zinovyevna Rosenbaum; 1905 – 1982), better known as Ayn Rand, was a Russian-American writer and philosopher. In her philosophy, Objectivism, she advocates rational self-interest and an ethic of production and exchange. Ayn Rand’s main arguments are: Rejection of altruism: Rand defines “altruism” (in the moral sense, not casual kindness) as the ethical doctrine that an individual has a moral obligation to live for the benefit of others and to sacrifice their own happiness and interests for the “greater good.” She argues that this is “moral cannibalism,” as it turns the productive into servants of the unproductive. The virtue of selfishness: Rand famously argued that “selfishness,” properly understood as rational self-interest, is a virtue. This means recognizing one’s own life and happiness as the supreme value and living according to one’s own judgment, without sacrificing oneself for others or sacrificing others for oneself. In her book Atlas Shrugged, she argues directly or indirectly against the idea of living off the labor of others, emphasizing themes such as production, independence, and opposition to “parasites” (those who beg for undeserved benefits) and “plunderers” (those who take them by force). “Money is not the tool of parasites, who claim their product with tears, nor of plunderers, who take it by force. Money is only possible thanks to the men who produce it.“ “An honest man is one who knows that he cannot consume more than he has produced.” “Only a ghost can exist without material property; only a slave can work without the right to the product of his labor. The doctrine that ‘human rights’ are superior to ‘property rights’ simply means that some human beings have the right to transform others into property; since the competent have nothing to gain from the incompetent, it means the right of the incompetent to possess their superiors and use them as productive livestock.” “I swear—by my life and my love for it—that I will never live for another man, nor will I ask another man to live for mine.” • “We’ve heard it said that the industrialist is a parasite, that his workers support him, create his wealth, make his luxury possible—and what would happen to him if they abandoned him? Very well. I intend to show the world who depends on whom, who supports whom, who is the source of wealth, who makes the support of whom possible, and what happens to whom when whom withdraws.” “If some men have a right to the products of the labor of others, it means that those others are deprived of rights and condemned to slave labor. Any supposed ‘right’ of one man, which implies the violation of the rights of another, is not and cannot be a right. No man can have the right to impose an unchosen obligation on another.“ “…it is immoral to live off one’s own effort, but moral to live off the effort of others—it is immoral to consume one’s own product, but moral to consume the products of others—it is immoral to gain, but moral to live at the expense of others… it is bad to profit from conquest, but it is good to profit from sacrifice…“ |

Origin and Evolution of “Utopian”

The term “utopian” originates from Thomas More’s 1516 book “Utopia,” which described an ideal society characterized by religious tolerance and the absence of private property. Over time, “utopian” came to mean any visionary or impractical scheme of social perfection. In the context of socialism, the term “utopian socialism” was coined by Friedrich Engels and Karl Marx to describe early 19th-century socialists such as Saint-Simon, Fourier, and Owen, who proposed detailed plans for ideal societies. This label was pejorative, intended to discredit its formulators on the grounds of naiveté and detachment from the realities of industrial capitalism, and to valorize their own concept of socialism, which they arrogantly labeled scientific, focused on historical materialism and class struggle.

The criticism, while pertinent (the ‘utopian’ socialists are indeed utopian), is quite irrational coming from Engels and Marx (two authors with a poor understanding of reality, economics, and the limitations of human action).

Science consists, among other things, in experimenting and verifying whether its theses are true. Thus, having a project to implement and test whether the ideal community model is functional brings the mindset of the “utopians” closer, in some way, to scientific logic. It only does so because science is a process of producing knowledge and not of changing society. Attempts at social change can be classified as social engineering, not as science, per se.

On the other hand, returning to Engels and Marx, claiming to possess an unfalsifiable “scientific” truth (as is the case with their “scientific” socialism) is anything but scientific. This ability to name, change the meaning of words, boast of knowing the “truth” and the “correct path,” while emptyly praising oneself (calling one’s “unscientific” scientific socialism) is an element of the revolutionary socialist mindset that persists to this day in radical leftism.

Characterizing “Utopian” Socialism

That said, we can characterize utopian socialism as one that embraces institutional design (a blueprint), focusing on planned communities as a legitimate endeavor, in contrast to revolutionary socialism’s focus on class struggle.

| Hayek and his critique of social engineering In his book The Counter-Revolution of Science, Friedrich August von Hayek (1899-1992), Nobel Prize winner in Economics (1974) makes the following criticism of social engineering: In recent years this desire to apply engineering technique to the solution of social problems has become very explicit; “political engineering” and “social engineering” have become fashionable catchwords which are quite as characteristic of the outlook of the present generation as its predilection for “conscious” control; in Russia even the artists appear to pride themselves on the name of “engineers of the soul,” bestowed upon them by Stalin. These phrases suggest a confusion about the fundamental differences between the task of the engineer and that of social organizations on a larger scale which make it desirable to consider their character somewhat more fully. We must confine ourselves here to a few salient features of the specific problems which the professional experience of the engineer constantly bring up and which determine his outlook. The first is that his characteristic tasks are usually in themselves complete: he will be concerned with a single end, control all the efforts directed towards this end, and dispose for this purpose over a definitely given supply of resources. It is as a result of this that the most characteristic feature of his procedure becomes possible, namely that, at least in principle, all the parts of the complex of operations are preformed in the engineer’s mind before they start, that all the “data” on which the work is based have explicitly entered his preliminary calculations and been condensed into the “blue-print” that governs the execution of the whole scheme. The engineer, in other words, has complete control of the particular little world with which he is concerned, surveys it in all its relevant aspects and has to deal only with “known quantities.” So far as the solution of his engineering problem is concerned, he is not taking part in a social process in which others may take independent decisions, but lives in a separate world of his own. The application of the technique which he has mastered, of the generic rules he has been taught, indeed presupposes such complete knowledge of the objective facts; those rules refer to objective properties of the things and can be applied only after all the particular circumstances of time and place have been assembled and brought under the control of a single brain. His technique, in other words, refers to typical situations defined in terms of objective facts, not to the problem of how to find out what resources are available or what is the relative importance of different needs. He has been trained in objective possibilities, irrespective of the particular conditions of time and place, in the knowledge of those properties of things which remain the same everywhere and at all times and which they possess irrespective of a particular human situation. |

Questions for reflection:

1. Is it possible to control all of human beings’ desired ends to build a society that serves them? If not, who will decide which ends people desire to be met? Or rather, whose desired ends will be met?

2. Is it possible to control all the variables that determine the production of goods and services in a society?

3. Are you satisfied with the public services you receive? If not, why don’t these services satisfy you?

4. If the state were to become responsible for producing more goods and services than it does today (replacing the market), what would happen? Do you think you would be more satisfied with these new services (provided by the state) or with the old ones (provided by companies in the market)?

5. Is it fair to take away property and rights from some people and grant them to others based solely on the claim that the former are wealthier than the latter?

Leave a comment