Introduction

Henri de Saint-Simon (1760-1825) is recognized as a central figure in the development of utopian socialism, an early 19th-century intellectual movement that sought to envision ideal societies. Born into a French aristocratic family, his life was marked by significant experiences, such as his participation in the American Revolution and periods of extreme poverty, including a suicide attempt in 1823. These experiences shaped his critical view of social and economic structures, leading him to propose a new social order detailed in works such as Le Nouveau Christianisme (1825).

Figure 18: Portrait de Claude-Henri de Rouvroy comte de Saint-Simon

Author: Hippolyte Ravergie (1815- ?)

Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Portrait_de_Claude-Henri_de_Rouvroy_comte_de_Saint-Simon.jpg

Biographical and Historical Context

Saint-Simon was born in Paris on October 17, 1760, into an aristocratic family. His education was uneven, and at 17, he entered military service, participating in the American Revolution as an artillery captain at Yorktown in 1781. During the French Revolution, he remained in France, acquiring nationalized lands, but he subsequently faced financial difficulties, which appears to have influenced his critique of leisured elites. His suicide attempt in 1823 reflects the personal challenges he faced, but his ideas continued to gain traction, especially after his death on May 19, 1825.

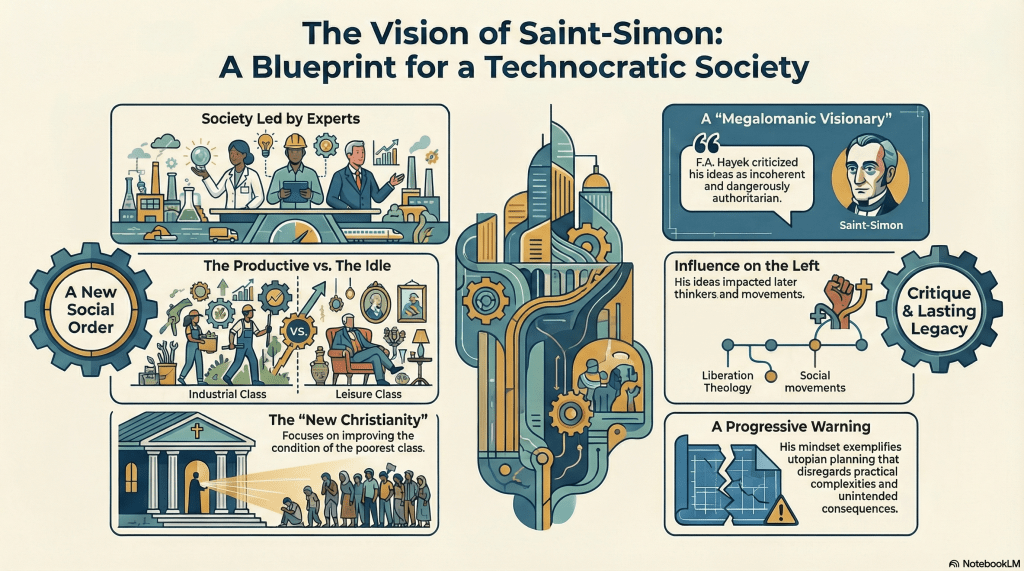

Vision of an Industrial Society

Saint-Simon is often credited with being the first to foresee global industrialization. He naively believed that science and technology could solve most human problems, proposing a society organized around productive labor. In opposition to feudalism and militarism, he advocated a technocracy formed by industrialists, scientists, and engineers, leading and assuming the role that the Roman Catholic Church had in the Middle Ages. His vision included a clear distinction between:

Industrial class: All those engaged in productive work, such as entrepreneurs, managers, scientists, bankers, and manual laborers, who contributed to social progress.

Leisure class: Able-bodied individuals who preferred a parasitic life, without contributing to the economy or society.

This division reflects his belief that society should be organized to maximize productivity, with the most capable in charge.

Technocratic Elite and Meritocracy

One of the central aspects of his thinking was meritocracy, where individuals would be promoted based on their abilities, not their birth. He proposed that scientists and engineers should run society, reflecting an elitist, technocratic vision, lacking an adequate understanding of human nature (and how personal and group interests shape human action) or of what science is and its limits.

| Hayek and Saint-Simon Friedrich August von Hayek (1899-1992), Nobel Prize winner in Economics (1974), in his book “The Counter-Revolution in Science,” makes, among other things, the following analysis of Saint-Simon’s thought: “§ 1. Early training and experience can hardly be said to have qualified the count Henri de Saint-Simon for the role of a scientific reformer. (…) (…) § 2. The visit to Switzerland was also the occasion of Saint-Simon’s first publication. In 1803 there appeared in Geneva the Lettres d’un habitant de Geneve a ses contemporains,60 a little tract in which the Voltairean cult of Newton was revived in a fantastically exaggerated form. It begins by proposing that a subscription should be opened before the tomb of Newton to finance the project of a great “Council of Newton” for which each subscriber is to have the right of nominating three mathematicians, three physicists, three chemists, three physiologists, three litterateurs, three painters and three musicians. The twenty-one scholars and artists thus elected by the whole of mankind, and presided over by the mathematician who received the largest number of votes, should become in their collective capacity the representatives of God on earth, who would deprive the Pope, the cardinals, bishops and the priests of their office because they do not understand the divine science which God has entrusted to them and which some day will again turn earth into paradise. In the divisions and sections into which the supreme Council of Newton will divide the world, similar local Councils of Newton will be created which will have to organize worship, research and instruction in and around the temples of Newton which will be built everywhere. Why this new “social organization,” as Saint-Simon calls it for the first time in an unpublished manuscript of the same period? Because we are still governed by people who do not understand the general laws that rule the universe. “It is necessary that the physiologists chase from their company the philosophers, moralists and metaphysicians just as the astronomers have chased out the astrologers and the chemists have chased out the alchemists.” The physiologists are competent in the first instance because “we are organized bodies; and it is by regarding our social relationships as physiological phenomena that I have conceived the project which I present to you.” But the physiologists themselves are not yet quite scientific enough. They have yet to discover how their science can reach the perfection of astronomy by basing itself on the single law to which God has subjected the universe, the law of universal gravitation. It will be the task of the Council of Newton by exercising its spiritual power to make people understand this law. Its tasks, however, go far beyond that. It will not only have to vindicate the rights of the men of genius, the scientists, the artists and all the people with liberal views; it will also have to reconcile the second class of people, the proprietors, and the third, the people without property, to whom Saint- Simon addresses himself specially as his friends and whom he exhorts to accept this proposal which is the only way to prevent that “struggle which, from the nature of things, necessarily always exists between” the two classes. All this is revealed to Saint-Simon by the Lord himself, who announces to His prophet that He has placed Newton at His side and entrusted him with the enlightenment of the inhabitants of all planets. The instruction culminates in the famous passage from which much of later Saint-Simonian doctrine springs: “All men will work; they will regard themselves as laborers attached to one workshop whose efforts will be directed to guide human intelligence according to my divine foresight. The supreme Council of Newton will direct their works.” Saint-Simon has no qualms about the means that will be employed to enforce the instructions of his central planning body: “Anybody who does not obey the orders will be treated by the others as a quadruped.” In condensing we had to try and bring some order into the incoherent and rambling jumble of ideas which this first pamphlet of Saint-Simon represents. It is the outpouring of a megalomaniac visionary who sprouts half-digested ideas, who all the time is trying to attract the attention of the world to his unappreciated genius and to the necessity of financing his works, and who does not forget to provide for himself as the founder of the new religion great power and the chairmanship of all the Councils for life.” |

The “New Christianity” and its Integration with Politics

In Le Nouveau Christianisme, Saint-Simon proposes a reformulation of Christianity, seeking to eliminate its metaphysical elements (such as belief in God or an afterlife) and transform it into a system focused on social redistribution. He writes: “Religion must direct society toward the great goal of the most rapid possible improvement of the condition of the poorest class” (Saint-Simon, 1825).

In a progressive vision, the new Church would mobilize scientists and industrialists, uniting spiritual and temporal power to combat what it sees as the vices of society: selfishness and idleness.

Economic Visions and State Intervention

Saint-Simon advocated a market economy with minimal state intervention, reducing taxes and militarism. The state should facilitate industrial organization, promoting the efficiency of the industrial class without directly controlling it.

Influence and Legacy

Saint-Simon’s ideas had a significant impact on later left-wing thinkers and movements. His technocratic vision of placing the direction of society in the hands of “experts” still echoes in the totalitarian bureaucratic thinking of part of the left.

His attacks on religion, attempting to transform it into a political instrument for redistribution, influenced radical leftist thought and even movements within the Catholic Church, such as the Liberation Theology movement.

A characteristic of the progressive mindset is a simplified worldview that sees social institutions as moldable at will, without considering the existence of trade-offs (human institutions are fallible and imperfect. Choices are always mandates for optimization, which must consider gains and losses) and unintended consequences (all the consequences of proposed changes are rarely known ex ante). Saint-Simon can be considered one of the earliest exponents of this mindset.

Summary Table: Central Aspects of Saint-Simon’s Ideas

| Aspect | Description |

| Industrialism: | Prediction of industrialization, society led by scientists and industrialists |

| Meritocracy: | Hierarchy based on merit, with scientists and engineers in charge |

| New Christianity: | Renewed religion, devoid of metaphysical aspects, uniting politics and society, focused on the well-being of the poor |

| Industrial Class vs. Idle Class: | Productive (scientists, workers) vs. parasitic (non-taxpayers) |

| Economy: | Market with minimal intervention, reduction of militarism and taxes |

| Influence: | Impact on Comte, Marx, Saint-Simonians, and social movements |

Connection to the Diagram of Political Mindsets

Claude-Henri de Saint-Simon is classified as a Socialist (a radical leftist) in the Circular Diagram of Western Political Mentalities, positioned near the Socialist–Social Democrat boundary (moderate leftists). His utopian vision of a technocratic, cooperative society aligns with socialist (radical leftistm) principles of collective equality and planned economies, while his meritocratic governance, retention of private property, and progressive reforms echo Social Democratic and Modern Liberal elements, placing him slightly closer to Social Democracy.

Conclusion

Henri de Saint-Simon’s utopian socialist ideas represent an attempt to destroy core elements of existing society and create a new, imaginary society based on a pseudo-scientific technicality that links his godless religion with politics. Even today, Saint-Simon’s messianic mindset and proposals continue to influence radical leftist thinkers who seek idealistic solutions to social problems, disregarding the practical complexities of these solutions or their unintended consequences.

Selected Texts

Claude-Henri Saint-Simon The New Christianity Dialogues between a Conservative and an Innovator (1825)

(…)

RELIGIONS.

The New Christianity will be composed of parties nearly resembling those which at present compose the diverse heretical associations which exist in Europe and in America.

The New Christianity, as well as the heretical associations, will have its morals, its worship, and its dogma ; it will have its clergy, and its clergy will have their chiefs. But, notwithstanding this similitude of organization, New Christianity will be purged of all existing heresies. The doctrine of morality will be considered by the New Christians as the most important. Worship and dogma will only be regarded by them as accessories, having for their principal object to fix upon morality the attention of the faithful of all classes .

In the New Christianity, all morality will be deduced directly from this principle-” Men ought to treat each other as brothers. ” And this principle, which belongs to primitive Christianity, will experience a transfiguration ; after which, it will be presented as constituting the great end of all religious labour.

This regenerated principle will be presented in the following manner : -” Religion must direct society towards the great end of the most rapid possible amelioration of the condition of the poorest class.”

Those who ought to lay the foundation of the New Christianity, and constitute themselves the chiefs of the new church, are those most qualified to contribute, by their labours, to increase the well- being of the poor. The duties of the clergy will be reduced to the teaching of the New Christian doctrine, in the perfecting of which the chiefs of the church will labour without ceasing.

Such, in few words, is the character which, in present circumstances, true Christianity ought to develop. We proceed now to compare this idea of a religious institution with the religions which exist in Europe and America : from this comparison we shall easily collect a proof that all the pretended Christian religions which are now professed are nothing but heresies ; that is to say, that they do not tend directly to the most rapid possible amelioration ofthe well- being of the poor, which is the only object of true Christianity.

(…)

Questions for Reflection

1. Reflect on Saint-Simon’s advocacy for technocracy, where scientists and engineers lead society— in what ways might this parallel contemporary calls for expert-driven governance, like in climate policy or AI regulation by tech elites? What are the risks of implementing a society led by a technocratic elite? How will non-industrial groups behave?

2. Discuss the implications of Saint-Simon’s scientism, believing science can solve most human problems through bodies like the “Council of Newton”; how could this inform current debates on overreliance on scientific expertise during public health crises, such as the COVID-19 pandemic responses?

3. In what ways does Saint-Simon’s reformulation of Christianity into a “New Christianity” focused on social redistribution without metaphysical elements echo modern secular movements, like social justice activism or progressive theology in addressing poverty? What are the risks of Saint-Simon’s proposed changes to the Christian religion?

4. The blog notes Saint-Simon’s influence on Liberation Theology; how might this connection guide reflections on the role of faith-based activism in contemporary politics, such as in Latin American progressive movements or U.S. social gospel initiatives?

5. How might Saint-Simon’s meritocratic elitism, lacking deep insight into human nature, warn against the risks of bureaucratic overreach in contemporary totalitarian-leaning regimes or international organizations like the World Economic Forum?

6. Reflect on the historical context of Saint-Simon’s ideas, shaped by revolutions and personal hardships— what lessons can this offer for understanding how economic disruptions today, such as recessions or technological shifts, fuel utopian political ideologies?

7. Do you consider Saint Simon’s ideal society to be ideal for you?

Leave a comment