Introdução

François Marie Charles Fourier (1772–1837) was a French philosopher and utopian socialist whose ideas centered on reorganizing society to align with human nature and passions, aiming for harmony, cooperation, and universal happiness. His theories, often considered eccentric but influential, critiqued the social and economic systems of his time and proposed radical alternatives.

Critique of Industrial Society and “Civilization”

- Fourier believed that modern society, which he called “civilization,” was fundamentally flawed, leading to misery, inequality, and the suppression of human desires. He criticized capitalism, commerce, and industrialization for fostering competition, exploitation, and monotony.

- He argued that traditional social structures ignored human passions, forcing people into unfulfilling labor and unnatural social roles, which led to poverty, alienation, and conflict.

Theory of Passions

- Fourier posited that humans are driven by 12 core passions (e.g., senses, social bonds, ambition, variety, and harmony), which, if properly channeled, could lead to a fulfilling and harmonious life.

- He believed society should be structured to satisfy these passions rather than repress them. For example, he advocated for work to be enjoyable and varied to align with individuals’ natural inclinations.

Cosmological and Esoteric Ideas

- Fourier’s writings often included fantastical and speculative elements. He believed that his social system would align with cosmic laws, leading to ecological and even astronomical transformations (e.g., he predicted that oceans would turn into lemonade-like liquid in the future).

- He developed a complex taxonomy of human types (810 distinct personality types based on combinations of passions), which he believed would ensure diversity and balance within each phalanx.

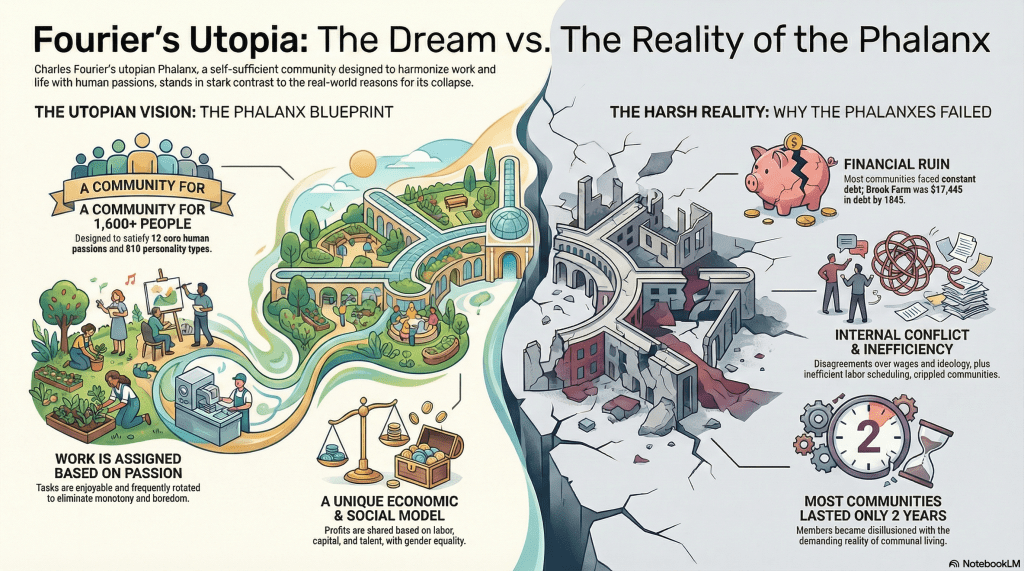

The Phalanx (Phalanstère)

- Fourier’s most famous proposal was the creation of self-sufficient, cooperative communities called phalanxes. He called the buildings in which the phalanxes would operate phalansteries (phalanstères), derived from “phalanx” (military formation) and “monastery.”

- The phalanx is a self-contained, cooperative community designed to house about 1,600–1,800 people, based on Fourier’s theory of human passions. Fourier identified 12 fundamental passions (e.g., senses, social bonds, ambition), which combine to create 810 distinct personality types, with a phalanx ideally including two of each type (1,620 people) to ensure diversity and balance. The purpose is to achieve social harmony by aligning work and living arrangements with individual desires, replacing the flaws of “civilization” with a system of mutual benefit and equity.

- Key features of the phalanx:

- Division of Labor Based on Passions: Work would be assigned according to individuals’ interests, with tasks rotated to avoid monotony. For example, someone who enjoyed gardening could work in agriculture, while those who liked intellectual pursuits could engage in study or planning.

- Collective Living: Members would live in a large, communal building (the phalanstère) with shared facilities for dining, education, and recreation.

- Education and Childcare: Children in the phalanx would be educated communally, with an emphasis on developing their natural talents and passions rather than enforcing rigid discipline.

- Economic Cooperation: The phalanx operates as a joint-stock company, with profits distributed based on three factors: labor, capital invested, and talent contributed. Work is voluntary, with hourly wages based on the disagreeableness of the task, ensuring fairness. Goods produced are the property of the phalanx, but private property and inheritance are permitted, distinguishing Fourier’s system from more radical socialism. The community aims for self-sufficiency through an agrarian-handicraft economy, including farming and small-scale manufacturing, with additional income from visitor fees.

- Social Harmony: Fourier believed that by satisfying passions and fostering cooperation, conflicts would be minimized, and social bonds would strengthen. He believed that his system would eliminate poverty, inequality, and war by aligning human activities with natural laws and desires

- Gender Equality and Sexual Freedom: Fourier was progressive for his time, advocating for gender equality and challenging traditional marriage. He proposed flexible relationships based on mutual attraction, arguing that repression of sexual desires led to social dysfunction.

Figure 19: North American Phalanx (abandoned)

Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Phalanxary_colt_nj.jpg

Reasons for Phalanx failures:

While Fourier’s vision promised utopia, real-world implementations revealed deep flaws rooted in human nature and economic realities. The mais causes of their failures are:

- Financial Struggles: Many phalanxes, like Brook Farm, faced constant debt and couldn’t sustain themselves financially. For example, Brook Farm accumulated $17,445 in debt by 1845, and a fire in 1846 caused a $7,000 loss, making recovery impossible.

- Practical Difficulties: Implementing Fourier’s ideas was tough in practice. The labor system, meant to be flexible and passion-driven, often led to inefficiencies, with members spending too much time on scheduling. Wage disparities also caused dissatisfaction, as seen in the North American Phalanx, where wages were lower than outside opportunities.

- Internal Conflicts: Disagreements within communities were common. Ideological shifts, like Brook Farm adopting a stricter Fourierist structure in 1844, led some members to leave. The North American Phalanx also faced splits over issues like women’s rights and slavery, weakening unity.

- External Setbacks: Events like fires and health crises added pressure. Brook Farm had a smallpox outbreak in 1845, infecting 26 members, and both Brook Farm and the North American Phalanx suffered devastating fires that destroyed key infrastructure.

- Lack of Long-Term Commitment: Many members grew disillusioned with the demanding communal life, finding the reality less appealing than the ideal. Most phalanxes lasted only about two years, reflecting the difficulty of maintaining enthusiasm.

- Cultural Resistance: Fourier’s radical ideas, such as communal living and gender equality, faced resistance from broader society, limiting support and making it hard to sustain the communities.

These factors combined to make Fourier’s phalanxes unsustainable.

Fourier antisemitism

Fourier expressed his anti-Semitic views in several key works, focusing on his critique of commerce and its association with Jews. These views are found in:

- Théorie des quatre mouvements et des destinées générales (1808): Here, Fourier described Jews as “the incarnation of commerce,” calling them parasitical, deceitful, and unproductive, and criticized their religious practices as disloyal to national culture.

- Traité de l’association domestique-agricole (1822): This work continued his critique, proposing Jews be integrated into phalansteries through farm work to counter their mercantile tendencies, referring to them as a “parasitic sect.”

- On the Federal Warehouse or the Abolition of Commerce (1810 manuscript): In this text, Fourier explicitly called Jews “a people addicted to traffic, to usury and to mercantile depravity,” comparing them to the corrupted Carthaginians.

These texts reflect Fourier’s economic and religious anti-Semitism, which evolved later with his advocacy for Jewish return to Palestine.

| Trade Creates Value Socialists generally believe that trade is a parasitic activity. This is related to a lack of understanding of what value is or how value is created. David Ricardo, a foundational economist, explained how trade creates value through his theory of comparative advantage. In his 1817 work, On the Principles of Political Economy and Taxation, he wrote: “Under a system of perfectly free commerce, each country naturally devotes its capital and industry to such employments as are most beneficial to each. This pursuit of individual advantage is admirably connected with the universal good of the whole. By stimulating industry, by rewarding ingenuity, and by using most efficaciously the peculiar powers bestowed by nature, it distributes labour most effectively and most economically: while, by increasing the general mass of productions, it diffuses general benefit, and binds together, by one common tie of interest and intercourse, the universal society of nations throughout the civilized world.” The argument applies to countries trading with each other, to the trade of jewelry between two individuals, and to almost any other trade. |

Connection to the Diagram of Political Mindsets

François Fourier is classified as a Socialist (a radical leftist) in the Circular Diagram of Western Political Mentalities, with a position near the Socialist (radical leftist) –Social Democrat boundary (moderate leftists). His utopian vision, cooperative phalanxes, and critique of capitalism align with socialist principles, while his allowance for private property, focus on individual passions, and progressive social views introduce Social Democratic and Modern Liberal elements. His antisemitism, however, highlights a collectivist flaw that clashes with liberal values and complicates his legacy. This placement reflects his radical yet idiosyncratic approach.

Influence and Legacy

- Approximately 50 phalanxes were established in the United States during the 19th century. The most notable example was Brook Farm, founded near Boston in 1841, which operated until 1847. The average duration of the other nearly 50 phalanxes in the United States was approximately two years. No phalanxes are still operating in the United States.

- In Brazil, his ideas served as inspiration for the Saí Phalanx in Santa Catarina (formed in 1841 and which in 1843 had only 9 of the original colonists and was considered extinct in 1864).

- Fourier’s antisemitism influenced some later left-wing antisemitic thinkers. This influence was part of a broader trend where some socialists associated Jews with capitalism.

Selected texts

Charles Fourier. The Utopian Vision of Charles Fourier Selected Texts on Work, Love and Passionate Attraction. 1971.

NEW MATERIAL CONDITIONS

THE ESTABLISHMENT OF A TRIAL PHALANX

We will suppose that the trial is made by a monarch, or by a wealthy individual like one of the Devonshires, Northumberlands, Bedforts, the Sheremetevs, Labanovs, Czartoryskis, the Esterhazys, Belmontes, Medina-Celis, the Barings, Lafittes, Hopes, etc., or finally by a powerful company which desires to avoid all tentative measures and proceed directly to the organization of Full Harmony, the eighth period in its plenitude. I am going to indicate the procedure to follow in this case.

An association of 1500 or 1600 people requires a site comprising at least one square league of land, that is to say a surface area of six million square toises . 1 (Let us not forget that one-third as much would suffice for the simple mode.)

A good stream of water should be available; the land should be hilly and suitable for a variety of crops; there should be a forest nearby; and the site should be fairly near a large city but far enough away to avoid unwelcome visitors.

The trial Phalanx will stand alone and it will get no help from neighboring Phalanxes. As a result of this isolation, there will be so many gaps in attraction, so many passional calms to fear in its maneuvers, that it will be particularly important to provide it with the help of a good site fit for a variety of functions. Flat country, like that surrounding Anvers, Leipzig or Orleans would be quite inappropriate and would cause the breakdown of many series, owing to the uniformity of the land surface. It will therefore be necessary to select a diversified region, like that near Lausanne, or at the very least a fine valley provided with a stream and a forest, like the valley from Brussels to Halle. A fine location near Paris would be the stretch of land between Poissy and Conflans, Poissy and Meulan.

The 1500 or 1600 people brought together will be in a state of graduated inequality as to wealth, age, personality, and theoretical and practical knowledge. The group should be as varied as possible; for the greater the variety in the passions and faculties of the members, the easier it will be to harmonize them in a limited amount of time.

All possible types of agricultural work should be represented in this trial community, including that involving hot-houses and conservatories. There should also be at least three types of manufacturing work for winter and for rainy days, as well as diverse types of work in the applied sciences and arts, apart from what is taught in the schools. A passional series will be assigned to each type of work, and it will divide up its members into subdivisions and groups according to the instructions given earlier.

At the very outset an evaluation should be made of the capital deposited as shares in the enterprise: land, material, flocks, tools, etc. This matter is one of the first to be dealt with; and I shall discuss it in detail further on. Let us now confine ourselves to saying that all these deposits of material will be represented by transferable shares in the association. 2 Let us leave these minute reckonings and turn our attention to the workings of attraction.

A great difficulty to be overcome in the trial Phalanx will be the formation of transcendent ties or collective bonds among the series before the end of the warm season. Before winter comes a passionate union must be established between the members; they must be made to feel a sense of collective and individual devo¬ tion to the Phalanx; and above all a perfect harmony must be established concerning the division of profits among the three elements: Capital, Labor and Talent.

The difficulty will be greater in northern countries than in those of the south, given the fact that the growing season lasts eight months in the south and just five months in the north.

Since a trial Phalanx must begin with agricultural labor, it will not be in full operation until the month of May (in a climate of 50 degrees latitude, like the region around London or Paris); and since the general bonds, the harmonic ties of the series, must be established before the end of the farming season in October, there will scarcely be five months of full activity in regions of fifty degrees latitude. Everything will have to be done in that short time.

Thus it would be much easier to make the trial in a region where the climate is temperate, for instance near Florence, Naples, Valencia or Lisbon where the growing season lasts eight or nine months. In such an area it would be particularly easy to consolidate the bonds of union since there would only be three or four months of passional calm between the end of the first season and the beginning of the second. By the second spring, with the renewal of its agricultural labors, the Phalanx would form its ties and cabals anew with much greater zeal and with more intensity than in the first year. The Phalanx would thence¬ forth be in a state of complete consolidation, and strong enough to avoid passional calms during the second winter.

(…)

THE PHALANSTERY

The edifice occupied by the Phalanx bears no resemblance to our urban or rural buildings; and in the establishment of a full Harmony of 1600 people none of our buildings could be put to use, not even a great palace like Versailles nor a great monastery like Escorial. If an experiment is made in minimal Harmony, with two or three hundred members, or on a limited scale with four hundred members, it would be possible, although difficult, to use a monastery or palace (like Meudon) for the central edifice.

The lodgings, gardens and stables of a society run by series of groups must be vastly different from those of our villages and towns, which are perversely organized and meant for families having no societary relations. Instead of the chaos of little houses which rival each other in filth and ugliness in our towns, a Phalanx constructs for itself a building as perfect as the terrain permits. Here is a brief account of the measures to be taken on a favorable site. . . .

The center of the palace or Phalanstery should be a place for quiet activity; it should include the dining rooms, the exchange, meeting rooms, library, studies, etc. This central section includes the temple, the tower, the telegraph, the coops for car¬ rier pigeons, the ceremonial chimes, the observatory, and a winter courtyard adorned with resinous plants. The parade grounds are located just behind the central section.

One of the wings of the Phalanstery should include all the noisy workshops like the carpenter shop and the forge and the other workshops where hammering is done. It should also be the place for all the industrial gatherings involving children, who are generally very noisy at work and even at music. The grouping of these activities will avoid an annoying drawback of our civilized cities where every street has its own hammerer or iron merchant or beginning clarinet player to shatter the ear drums of fifty families in the vicinity.

The other wing should contain the caravansary with its ballrooms and its halls for meetings with outsiders, who should not be allowed to encumber the center of the palace and to disturb the domestic relations of the Phalanx. This precaution of isolating outsiders and concentrating their meetings in one of the wings will be most important in the trial Phalanx. For the Phalanx will attract thousands of curiosity-seekers whose entry fees will provide a profit that I cannot estimate at less than twenty million. . .

The phalanstery or manor-house of the Phalanx should contain, in addition to the private apartments, a large number of halls for social relations. These halls will be called Seristeries or places for the meeting and interaction of the passional series.

These halls have nothing in common with our public rooms where ungraduated social relations prevail. A series cannot tolerate this confusion: it always has its three, four or five divisions which occupy three, four or five adjacent locations. This means that analogous arrangements are necessary for the officers and members of each division. Thus each Seristery ordinarily consists of three principal halls, one for the center and two for the wings of the series.

(…)

Questions for reflection

1. Is it reasonable to imagine that central planners are capable of providing solutions to all of civilization’s problems, from sexual relationships, marriage, child education, labor relations, job dissatisfaction, social conflicts, and others?

2. Is it possible to revoke all unpleasant tasks?

3. Is it possible to align all required tasks with individual preferences? Can a central planner do this? Isn’t this what the market does, taking into account individual capabilities and real-world constraints?

4. What do you think is more utopian, proposing that the idea of a phalanx be tested in a trial (like the one described in the selected text) to see if it works or simply destroying what exists so that a new society emerges from the chaos without the problems of the previous one (as proposed by the “scientific” socialists)?

5. How does the failure of American Fourierist communities—such as Brook Farm and North American Phalanx—due to financial problems and ideological schisms inform contemporary analyses of the sustainability of utopian political projects?

6. Reflect on Fourier’s esoteric elements, such as cosmic harmony and fantastical predictions, in shaping his utopian vision— in what ways might this mirror contemporary utopian ideologies, like those in Silicon Valley’s transhumanism or AI-driven societal redesigns?

7. Discuss the antisemitic undertones in Fourier’s critique of commerce and parasitism; how could this inform analyses of antisemitism resurfacing in modern left-wing movements that associate economic exploitation with specific ethnic or religious groups?

8. In what ways does Fourier’s taxonomy of personality types to ensure social balance echo modern psychological profiling in politics, such as voter segmentation or team-building in activist groups, and what ethical concerns arise from such categorizations?

Leave a comment