Introduction

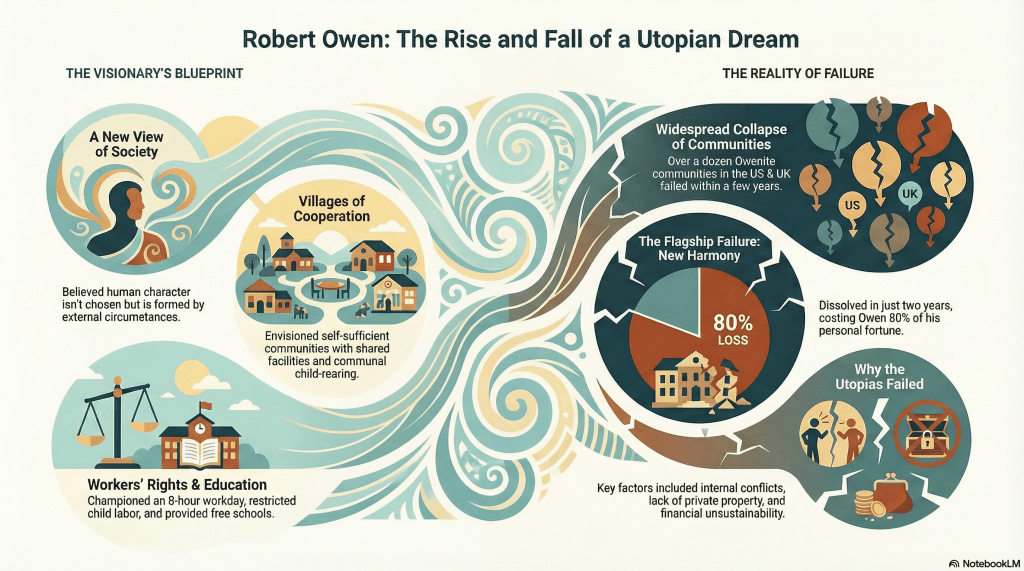

Robert Owen (1771–1858), a Welsh textile manufacturer turned social reformer, is widely recognized as a pioneer of utopian socialism and the co-operative movement. His ideas, rooted in a belief that human character is shaped by environmental conditions rather than individual control, aimed to create a more equitable and harmonious society. However, his ambitious efforts to implement these ideas faced significant challenges, leading to several notable failures.

Background and Context

Born on May 14, 1771, in Newtown, Wales, Owen gained wealth and influence through his management of the New Lanark mills in Scotland, where he implemented progressive reforms. His experiences during the Industrial Revolution, witnessing the harsh conditions faced by workers, particularly children, shaped his vision for social reform. By the early 19th century, he had become a prominent advocate for utopian socialism, seeking to address poverty, inequality, and exploitation through practical and theoretical means.

However, despite classifying himself as a socialist, Owen was a typical entrepreneur. After making a fortune in his New Lanark factory, he became convinced of his own ideals and decided to embark on an even more ambitious venture, New Harmony. The result was a short-term failure, and he lost most of his fortune in this venture.

Over a dozen Owenite communities were established in the US between 1825 and 1830, with at least 10 documented, and seven in the UK (including Ireland) between 1821 and 1845. None of these communities were successful in the long term, all failing within a few years due to economic, organizational, and social challenges.

Robert Owen’s Key Ideas

Owen’s ideas were multifaceted, focusing on improving societal structures through education, cooperative living, and workers’ rights. The following table summarizes his main concepts:

| Idea | Description |

| Improved Working Conditions | Advocated for better factory conditions, including fair wages, shorter hours, and restrictions on child labor. At New Lanark, he implemented reforms like reduced working hours and improved living conditions. |

| Lifelong Education | Believed in continuous education for personal development, establishing schools like the Institute for the Formation of Character, focusing on character over job skills. Supported free, co-educational schools. |

| Utopian Communities | Proposed self-sufficient villages of unity and cooperation, with 500–3,000 people on 1,000–1,500 acres, featuring shared facilities (kitchens, dining halls) and communal child-rearing after age three, aiming for a “New Moral World.” |

| Socialism and Cooperation | Criticized capitalism’s individualism, advocating for collective approaches. Supported the cooperative movement, including the National Equitable Labour Exchange (1832), using labor notes as currency. |

| Workers’ Rights | Championed trade unions, lobbied for legislative reforms like reducing child labor hours, and proposed an eight-hour workday with the slogan “eight hours labour, eight hours recreation, eight hours rest.” |

| Secularism | Critical of organized religion, developed a secular belief system emphasizing rational thought, influencing working-class views by 1839 through the Association of all Classes of all Nations (1835). |

For Owen, human character is shaped by circumstances. He argued that subjecting individuals to appropriate physical, moral, and social influences from childhood was fundamental to social reform, a principle he articulated in works such as “A New View of Society” (1813).

It is important to note that Owen’s socialism does not question private ownership of the means of production, nor does it seek to seize power by force or any of the more radical proposals of the years that would follow. It is oriented towards improving the quality of life of workers in private companies, which places him not as a strict radical leftist but much closer to moderate leftists.

Attempts to Implement His Ideas

Owen’s efforts to put his ideas into practice included both practical reforms at New Lanark and experimental communities, as well as legislative and organizational initiatives. Below is a detailed breakdown of these attempts, many of which failed:

– New Lanark Reforms: At New Lanark, Owen successfully improved working and living conditions, including building schools and reducing child labor hours. This model became a pilgrimage site for reformers but was not replicated on a larger scale due to its dependence on his personal management and resources.

– Utopian Communities:

- New Harmony, Indiana (1825–1827): Owen purchased this settlement to create a utopian community, attracting over 1,000 residents by the end of its first year. It aimed to embody his vision of cooperative living but dissolved in 1827 after about two years.

- Other U.S. Communities: Included Blue Spring (near Bloomington, Indiana), Yellow Springs (Ohio), and Forestville Commonwealth (Earlton, New York), all ending before New Harmony in April 1827.

- Orbiston, Scotland (1825): Orbiston faced challenges with funding, internal organization, and the ability to change the mindset of its inhabitants, ultimately leading to its collapse in 1827.

- Ralahine, County Clare, Ireland (1831–1833): Successful for 3.5 years but failed due to the proprietor’s gambling debts.

- Tytherley (Harmony Hall), Hampshire, England (1839–1845): Also know as Queenwood aimed to create a self-sufficient, cooperative society based on Owen’s socialist principles. However, the project faced significant financial and organizational challenges, ultimately failing to achieve its goals.

- Manea Colony, Cambridgeshire (late 1830s): Launched by disciple William Hodson, failed within a couple of years, after which Hodson emigrated to the U.S.

– Legislative and Organizational Efforts:

- Factory Reform (1815): Proposed reducing child work hours in mills, defeated in 1815. By 1817, agitation for factory reform had little effect, leading him to focus on theoretical socialism.

- Grand National Consolidated Trades Union (GNCTU, 1833–1834): Rallied 500,000 workers but collapsed due to opposition from employers and government.

- National Equitable Labour Exchange (1832–1833): Used labor notes as currency, failed after about a year due to practical challenges and lack of adoption.

- International Efforts: Following New Harmony, an attempt to institute a comparable experiment in Mexico in 1828 also failed, further depleting Owen’s resources.

Figure 19. New Harmony. Depicted as proposed by Owen.

Author. F. Bate

Source. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:New_Harmony,_Indiana,_por_F._Bates.jpg

Reasons for Failure

The failures of Owen’s initiatives can be attributed to a combination of internal and external factors, as detailed in the following table:

| Reason for Failure | Details |

| Lack of Individual Sovereignty and Private Property | The pursuit of happiness according to one’s own conceptions and the incentives of private enterprise were largely absent in New Harmony. |

| Heterogeneous Membership | New Harmony had diverse groups (radicals, theorists, opportunists), leading to internal conflicts and lack of cohesion. |

| Religious and Governmental Disputes | Disagreements over religion and governance caused division and failed reorganization attempts in communities like New Harmony. |

| Financial Loss | Owen lost significant wealth, including 80% (£40,000) after withdrawing from New Harmony in 1828, limiting further efforts. |

| Opposition by Employers and Government | GNCTU and labor exchanges faced strong opposition, leading to collapse. |

| Lack of Industry and Responsibility | New Harmony lacked the discipline and responsibility seen at New Lanark, contributing to failure. |

| Attack on Religion | Public criticism of religion alienated supporters, reducing influence. |

| Practical Challenges | Communities struggled with financial sustainability, internal conflicts, and difficulty maintaining self-sufficiency. |

These reasons highlight the complexity of implementing utopian social reforms in human societies where people are not and are not willing to give up their desires and ambitions to be what the reformers want them to be.

| Chris Calton on Robert Owen and Other Utopians Chris Calton is the Research Fellow in Housing and Homelessness at the Independent Institute. He received his Ph.D. in History from the University of Florida. In his article The First Socialists: The Saint-Simonians and the Utopians, written to the Von Mises Institute, he wrote about Owen utopian communities: ‘Unsurprisingly, the utopian communities failed, but the utopians shared two important ideas that survived in later theories. The first is their theory of human nature. Derived from John Locke’s notion of tabula rasa, thinkers increasingly considered the role of the social environment in shaping human behavior. Owen and Fourier represent extreme social determinism. This was an important basis of their society. They held that if they could create the right “social milieu,” pesky elements of human nature such as individual self-interest would disappear. In contrast to Sismondi’s idea of a conflict between the individual and general interest, Owen and Fourier believed that individual interests would become naturally subordinate to the collective. This is the second important idea that linked the utopians. While collectivism was implied in Sismondi’s idea of a “general interest” and had historical roots in Christian monasteries, Owen and Fourier offered the first formal expression of full socialist collectivization.’ (Full article can be read at https://mises.org/mises-wire/first-socialists-saint-simonians-and-utopians) |

Connection to the Diagram of Political Mindsets

Robert Owen is classified as a Socialist (radical leftist) in the Circular Diagram of Western Political Mentalities, positioned near the Socialist–Social Democrat boundary (moderate leftist). His utopian vision of cooperative communities, critique of capitalism, and emphasis on collective equality align with socialist principles, while his practical reforms, focus on education, and early market-compatible experiments echo Social Democratic and Modern Liberal elements. Compared to Fourier, Owen is more practical and less esoteric; compared to Saint-Simon, he is more community-focused and less elitist. This placement reflects his blend of radical collectivism with reformist pragmatism.

Legacy and Influence

Despite these failures, Owen’s ideas had a lasting impact. His vision for “villages of unity and cooperation” and his advocacy for mutual aid inspired the cooperative movement. His ideas were adapted, to become more practical, and his emphasis on education influenced cooperative learning programs.

Notable Quote:

“Any general character, from the best to the worst, from the most ignorant to the most enlightened, may be given to any community, even to the world at large, by the application of proper means; which means are to a great extent at the command and under the control of those who have influence in the affairs of men.” (A New View of Society, First Essay, as cited in Wikipedia: Robert Owen)

| Utopia and the Destruction of Human Nature Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky (1821-1881) was a Russian novelist, considered one of the greatest novelists of all time. He criticizes utopian socialist ideas (such as those similar to Owen’s environmental determinism) in Notes from Underground, arguing that attempting to mold human character into a perfectly rational and harmonious state through controlled means would destroy essential aspects of human nature—such as free will, irrationality, and the drive for independent choice—leading to inevitable rebellion and self-destruction: “Shower upon him every earthly blessing, drown him in bliss so that nothing but bubbles would dance on the surface of his bliss, as on a sea…and even then, for the sake of some caprice, from boredom alone, he will create destruction. […] He will even risk his gingerbread, and wish on purpose for the most pernicious nonsense, the most non economical meaninglessness, solely in order to mix into all this positive good sense his own pernicious, fantastical element. It is precisely his fantastic dreams, his most banal stupidity, that he will wish to keep hold of, with the sole purpose of confirming to himself (as if it were so very necessary) that human beings are still human beings and not piano keys, which, though played upon with their own hands by the laws of nature themselves, are in danger of being played so much that outside the calendar it will be impossible to want anything.” |

Conclusion

Some of Robert Owen’s ideas were and remain valid, such as the pursuit of better working conditions and lifelong education. However, his attempts to establish utopian socialist communities, such as New Harmony and other experimental communities, failed due to internal conflicts, financial losses, a lack of proper incentives for production, and other reasons. Despite these failures, Owen’s legacy endures in the cooperative movement.

Selected Texts

Robert Owen, SECOND DISCOURSE ON A NEW SYSTEM OF SOCIETY 1825.

(…)

The fact is, and I am most anxious that all parties should fully understand me, the system which I propose now for the formation and government of society, is founded on principles, not only altogether different, but directly opposed to the system of society which has hitherto been taught and practised at all times, in all nations; and, until the public mind can be elevated to this point, I shall not be understood; my attempt at explanation must fail to be comprehended, and an inexplicable confusion of ideas will alone remain. The error must be mine; I have not yet been sufficiently explicit; but upon this occasion, I must endeavour to put the contrast between the two systems, in such a point of view as not to be misunderstood. The old system of the world, by which I mean all the past and the present proceedings of mankind, presupposes, that human nature is originally corrupt – that man forms his own belief and his own character – that, if these shall be formed in a particular manner, the individual will deserve an artificial reward, both here and hereafter; but if this belief, and this character shall not be so formed, the individual will deserve an artificial punishment both here and hereafter. The theory of the old system is therefore founded on notions directly opposed to our nature, and its practice is individual rewards and punishments.

The new system presupposes that human nature is now what it ever has been, and will be, and what the power which produced it formed it to be originally; that man does not create his own belief, or his own character, physical or mental; that his belief and character are uniformly created for him, and that he cannot possess merit or demerit for the formation of either; that he is a compound being, formed by the impressions made by external circumstances, upon his individual nature, and, as he had no will, or knowledge, or power, in deciding upon the creation of either, he cannot become a rational object for individual reward or punishment; that man is a being formed to be irresistibly controlled by external circumstances, and to be compelled to act according to the knowledge which these circumstances produce in him; that a knowledge of this fact will compel him to make himself acquainted with the nature of circumstances, so as to understand the effects which they will produce on human nature, and, through that knowledge, compel him to govern all circumstances, within his control, for the benefit of his own and succeeding generations.

The old system has been influenced in all ages, by some imaginary notions or other, under the name of religion, but which notions have been, in all countries, uniformly opposed to facts, and, in consequence, all minds have been thereby rendered more or less irrational. The new system, as I have previously stated, adopts a religion derived from the facts which demonstrate what human nature really is, and which facts give to man all the knowledge he possesses respecting himself; it is, therefore, called rational religion, or a religion of demonstrable truth, of intelligence, and of universal charity and benevolence, and derived from the evidence of our senses.

The old system keeps its votaries in ignorance, makes them mere localized beings, and the perpetual slaves of a combination of the most inferior and worst circumstances, and, in consequence, society is a chaos of superstition, passion, prejudice, poverty in many, and ignorance of their real interest in all; while the new system makes man familiar with his true interests, and, in consequence, gives him the knowledge and power to combine and govern circumstances in such a manner as to secure it, and unerringly to produce happiness to himself and others.

And this is the practical point at which I wished to arrive to produce benefit from this discourse. In my former address, I stated that, to produce the greatest happiness for the greatest number, three things were necessary:

1st. A proper training and education, from birth, of the physical and mental powers of each child.

2d. Arrangements to enable each individual to procure, in the best manner, at all times, a full supply of those things which are necessary and the most beneficial for human nature; and

3d. That all individuals should be so combined in a social system, as to give to each the greatest benefits from society.

Now, practical arrangements to produce these results have never yet been formed, or any thing, approaching to them. They cannot be found in any single and detached dwelling, in any village, town, or city, in any part of the world. I am, therefore, justified in saying, that, like old machines, when a new one of very superior powers has been invented to supersede them, separate dwelling houses, villages, towns, and cities, must give place to other combinations.

Now, if circumstances possess an overwhelming and irresistible influence over the whole human race, so as to make every individual either happy or miserable, is it not of the last importance to all of us, to become learned in that science, an accurate knowledge of which will enable the present generation to remove misery from the succeeding one, and secure happiness to their posterity?

What other subject can be brought into comparison with this? Or rather, when compared with it, do not all other subjects either lose their value or become extremely insignificant?

If I am right, the first and most important inquiry for human beings ought to be, to ascertain what circumstances produce evil, and what good, and how circumstances can be arranged to produce the latter, and exclude the former. To become learned in these matters of the deepest interest to my fellow men, has been the study and practice of my life; and as the result of such study and practice, I submit for your most serious consideration the new combination of circumstances which are now before you. They have been very hastily put together by Mr Hutton of this city/ since our last meeting, and cannot be expected to give more than a very imperfect sketch of the outline of the plan, as it will appear in actual practice.

I am now prepared to say, with a confidence that fears no refutation, and which nothing, except being fully master of the whole subject, could so impress on my mind, that all existing external human or artificial circumstances must speedily give place to these. And, as the essential interests of each one, whatever may be his present rank, station, or condition, in the world, will be promoted to an incalculable extent by the change, I trust that one and all who are present, and the whole American population, will now begin to study the subject, and, when masters of it, assist each other with all their power to remove, speedily, the present wretched and irrational circumstances, and to replace them by others which must, of necessity, make them intelligent and happy.

(…)

Questions for Reflection

- The pursuit of better working conditions seems to be almost a universal pursuit (very few would disagree). Does building a socialist community seem to be the best way to achieve such a result?

- Are people’s minds a blank slate on which we can freely write whatever we want?

- Is an ideal society one in which we change people’s minds so they can live according to a preconceived plan, or one that adapts to who people are and aspire to be?

- Can a socialist enterprise compete with capitalist enterprises (for a first analysis, disregard cooperatives in your answer, as they are not inherently socialist companies)? Why? Who will provide better products at lower costs? Who is most likely to sustainably improve the living conditions of their workers? In the long run, which enterprises will be wealthier and generate more value for society?

- Is it reasonable to assume that the set of beliefs about human nature that has organized all of Western society is wrong? Are there no lessons worth learning?

- Are rewards and punishments important in social organization, or can education solve all human misbehavior?

- The failure of the Owenite communities occurred in a free market environment, resulting in losses only for investors. How great would the loss be resulting from the failure to implement a new mode of production across an entire country?

- Is humanity peaceful and orderly, bees that follow the command of their queen, or is it simply chaotic?

- How many failures does it take to realize an idea is a bad idea?

- What lessons can be learned from Owens’ failures?

Leave a comment