The Frankfurt School refers to a group of scholars associated with the Institute for Social Research, founded in 1923 at Goethe University in Frankfurt, Germany. Key figures include Max Horkheimer, Theodor Adorno, Herbert Marcuse (first generation), and Jürgen Habermas (second generation). It developed a interdisciplinary approach known as Critical Theory, which aimed to critique and transform society by analyzing power structures, ideology, and culture through a Marxist lens, often incorporating insights from psychoanalysis, philosophy, and sociology. The school was influenced by the rise of fascism, capitalism, and mass media, and its members were mostly Jewish intellectuals who fled Nazi Germany in the 1930s, relocating temporarily to the United States before some returned to Germany post-World War II.

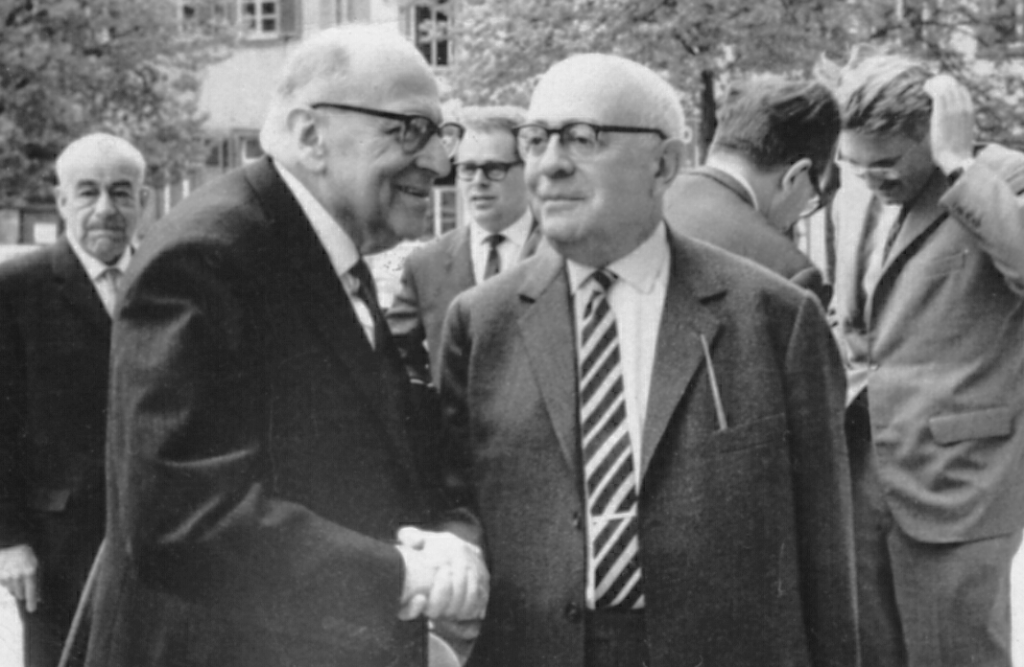

Figure 22. Max Horkheimer and Theodor W. Adorno. Back left: Siegfried Landshut. Right back (hand in hair): Jürgen Habermas.

Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:AdornoHorkheimerHabermasbyJeremyJShapiro2.png

Main Ideas on Politics

The Frankfurt School’s political ideas center on critiquing structures of domination, authoritarianism, and the erosion of critical thought in modern societies. They viewed politics not as isolated from economics or culture but as intertwined with them, often leading to repression and false consciousness.

Critique of Authoritarianism and Fascism: Early work focused on explaining the rise of Nazism and authoritarian regimes. In studies like The Authoritarian Personality (1950), Adorno and collaborators identified psychological traits—such as rigid conformity, prejudice, and submission to authority—that make individuals susceptible to fascist ideologies. They linked these to social crises, family dynamics, and broader political-economic conditions, arguing that capitalism’s instabilities foster irrational obedience and domination rather than rational emancipation.

Although the initial focus was antisemitism, the study concluded that prejudice against Jews was not a specific or isolated phenomenon, but rather “part of a broader ideological structure.” Antisemitism is seen as an aspect of a general ethnocentric ideology. The aim of the study was, in fact, to examine the relationship of prejudice against minorities to broader ideological and characterological patterns.

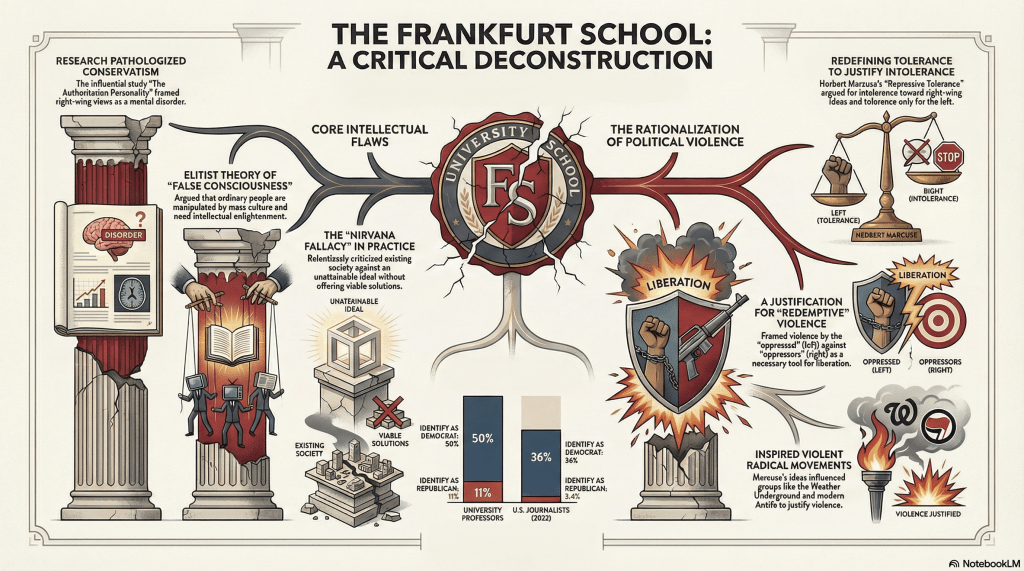

| Methodological Flaws, Left-Wing Bias The Authoritarian Personality (1950), by Theodor Adorno, Else Frenkel-Brunswik, Daniel Levinson, and Nevitt Sanford, is a work of social psychology that sought to explain the psychological roots of fascism and prejudice, particularly after World War II and the Holocaust. It introduced the F-scale (Fascism scale) to measure authoritarian tendencies, relating them to personality traits shaped by a rigorous upbringing, such as conventionalism, submission to authority, aggression toward outgroups, and anti-intraception (rejection of subjectivity). The study argued that these traits make individuals susceptible to anti-democratic ideologies. Although influential, the study has faced substantial criticism over the decades for methodological reasons, theoretical, empirical, and ideological limitations. We will focus here only on the ideological issues. The work has a strong ideological bias, rooted in the authors’ Marxist leanings (they are radical leftists), whose premises: a) pathologize right-wing views as mental disorders, while inducing the idea of mental health linked to leftist values (as if every leftist were a moderate/democratic leftist, forgetting radical leftists, like themselves, moderate conservatives, and classical liberals, the latter being the true opponents of fascism and authoritarianism in general); b) attribute a fascist character to free-market capitalism (which is devoid of historical and logical sense. In fascism, the capitalist is controlled by the interests of the State); c) they mistakenly characterize fascism as a right-wing phenomenon, which denies historical facts, such as the well-known migration of people associated with socialist parties to the German Nazi and Italian Fascist parties, including Mussolini himself, an active member of the Italian Socialist Party, who became disillusioned with it and founded the National Fascist Party (see the chapter on Mussolini). d) they disregard a basic element of conservative thought: pragmatic, not utopian, thinking. They support and vote for the lesser evil, not the (non-existent) ideal. That is, under political circumstances, the conservative middle class supported what seemed lesser evil to them, which does not mean they became fascists, but that they were against the communists. e) characterize prejudice against Jews as a central element of fascism, which is only true of German Nazism, not Italian fascism (which inspired German fascism). f) disregard the fact that a substantial portion of humanity has an authoritarian mindset and that, in the United States, where the studies were conducted, the middle class accounts for the majority of the population (thus, it was easy to find people with an authoritarian mindset in the middle class).In communist countries, the authoritarian mentality remains present, but now in the proletarian class (and in its leaders, as revealed by the history of the USSR, China and North Korea, among others), given that there is no middle class (the entire population has been impoverished). In fact, I suspect that anyone who preaches the dictatorship of the proletariat displays authoritarian traits. As a result, they link fascist potential (high F scores) to what they call pseudoconservatism (pseudoconservatives are characterized by professing traditional values but secretly harboring subversive and destructive impulses, aiming to abolish the institutions they claim to defend). It turns out that such a person is already a proto-fascist (see the chapter on Alfredo Rocco), one of the Radical Statist types and not a moderate conservative (although his mentality closely resembles that of the Authoritarian Conservative, bearing in mind the fluidity of the classification and the lack of clear boundaries between the types). Adorno himself recognizes that the conservatism that strongly correlates with prejudice is not traditional conservatism, but pseudo-conservatism. However, it did not occur to him to examine the radical mentality of the left, which is known to be prejudiced against Jews. Historically, one can cite Fourier and Karl Marx (see the respective chapters) as examples of left-wing authors with recognized prejudice against Jews. Or the case of Stalin, systematically accused of anti-Semitism, a fact that Adorno should have been aware of. Currently, this leftist prejudice is clearly manifest in the radical left’s strong support for Hamas, an Islamic terrorist group that advocates the destruction of the State of Israel and the extermination of the Jews. Finally, it is worth mentioning the historical problem of prejudice against Jews throughout Europe, which involves all authoritarians, right-wing and left-wing, a fact that Adorno should have known. |

The Culture Industry and Mass Manipulation: Horkheimer and Adorno, in Dialectic of Enlightenment (1947), argued that mass media and popular culture (the “culture industry”) standardize thought and behavior, turning citizens into passive consumers. This serves political ends by numbing critical capacities, reinforcing conformity, and preventing resistance to oppressive systems. They saw this as an extension of Enlightenment rationality gone awry, where instrumental reason dominates, leading to a “totally administered society” with little room for genuine political agency.

| Dialectic of Enlightenment Main Flaws Dialectic of Enlightenment (1944/1947), co-authored by Max Horkheimer and Theodor W. Adorno, is a foundational text of the Frankfurt School’s critical theory. Written during their exile in the United States amid World War II, it argues that the Enlightenment’s promise of reason, progress, and liberation has dialectically reverted into myth, barbarism, and domination. While influential in philosophy, sociology, and cultural studies, the book has faced significant criticisms for its methodology, theoretical assumptions, and implications. Performative Contradiction and Self-Undermining Critique: A central critique, notably from Habermas, is that Horkheimer and Adorno engage in a “performative contradiction” by using rational argumentation to denounce reason itself as inherently dominating and mythical. This undermines the rational grounds of their own claims, creating an aporia where critique becomes impossible without relying on the very tools they condemn. Exaggerated and Totalizing View of Reason and the Enlightenment:The authors are accused of painting an exaggerated, undifferentiated picture of enlightenment as inevitably leading to domination, ignoring its positive achievements in science, ethics, and art. Excessive Pessimism and Absence of Hope: The text’s bleak outlook—that enlightenment reverts to myth and a “fully enlightened earth radiates disaster triumphant”—is seen as overly deterministic and nihilistic, offering no viable path forward. No Practical Solutions or Alternatives: Horkheimer and Adorno provide no concrete alternatives to the domination they diagnose, with hope relegated to vague, messianic recognition of “lacks” rather than actionable change. Rhetorical Exaggeration and Lack of Nuance: The book’s aphoristic, non-argumentative style—accumulating distortions to “wake” readers—is criticized for mirroring the instrumental reason it attacks, potentially exaggerating claims for effect rather than precision. Narrow Focus and Omissions: Some argue it overemphasizes technology and instrumental reason while underplaying other factors like economic or social dynamics. It also neglects “really existing socialism” (e.g., Stalinism) in its critique of totalitarianism. Elitism: The critique of the culture industry as mass deception is elitist, dismissing popular culture without acknowledging its valuet. |

One-Dimensional Society and Resistance: Marcuse, in One-Dimensional Man (1964), described advanced industrial societies as “one-dimensional,” where critical opposition is absorbed into the system through consumerism and technology. Politics becomes technocratic, reframing social issues as managerial problems. He advocated for a “Great Refusal”—radical rejection by marginalized groups, students, and social movements—to challenge this, envisioning liberation through new forms of morality, aesthetics, and sensuality that transcend capitalist repression.

| Main Criticisms of the One-Dimensional Man Herbert Marcuse’s “One-Dimensional Man – Studies in the ideology of advanced industrial society” published in 1964, has faced substantial criticism since its publication, questioning both its theoretical foundations and practical implications. False Equivalence Between Capitalism and Totalitarianism: Marcuse’s portrayal of capitalist democracies as “totalitarian” in disguise that downplays real totalitarian regimes like Soviet communism. Elitist Imposition of Change: Marcuse envisions a radical minority (e.g., students, intellectuals) imposing “liberation” on a passive majority, bypassing democratic processes. This is viewed as arrogant and dangerous, echoing communist vanguards and leading to irrational suppression of dissent. It dismiss the working class’s contentment with capitalism as “false consciousness” while empowering unelected elites. Rejection of Human Nature and Progress: Marcuse’s view of human needs as malleable is criticized as denying inherent human traits and the benefits of technological advancement. He ignores how capitalism has actually improved people’s lives. Overstated Pessimism and Lack of Evidence: Marcuse’s claims of systemic repression are exaggerated and unsupported by, among others, the counterexample of the United States’ history of free speech and mobility. His abstract, dialectical style serves more as an ideological justification than as an analysis of reality. |

Communicative Action and the Public Sphere: Habermas shifted toward a more optimistic view, emphasizing “communicative action” based on rational discourse and mutual understanding. In The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere (1962) and The Theory of Communicative Action (1981), he critiqued how mass media and bureaucracy distort public debate, turning active citizens into spectators. He proposed deliberative democracy—where validity claims (truth, rightness, sincerity) are tested in ideal speech situations—as a path to political emancipation, countering ideological distortions.

| Nirvana Fallacy The Nirvana Fallacy refers to the dismissal of practical, real-world options or systems because they do not achieve an unattainable ideal of perfection, often resulting in inaction or endless criticism without constructive alternatives. The Frankfurt School, through its emphasis on negative dialectics and immanent critique, exemplifies this by scrutinizing societal contradictions, such as capitalism’s promotion of instrumental reason leading to alienation and fascism (a mischaracterization). Thinkers like Adorno avoided concrete proposals, fearing that any affirmative program could be co-opted by the oppressive systems they opposed, prioritizing exposure of flaws over actionable solutions. This approach embodies the Nirvana Fallacy, as the School relentlessly highlights the imperfections of existing society—such as the manipulative “culture industry”—while implicitly comparing it to an unarticulated, perfect emancipatory ideal that remains unrealized. |

Overall, their political thought is pessimistic about existing systems but committed to “emancipation” through self-reflection and critique, rejecting both liberal capitalism (wrongly accused of being fascist) and Soviet-style communism as forms of domination.

Key quotes

Max Horkheimer and Theodor W. Adorno: “For enlightenment, anything which does not conform to the standard of calculability and utility must be viewed with suspicion” (From Dialectic of Enlightenment.)

Herbert Marcuse: “The people recognize themselves in their commodities; they find their soul in their automobile, hi-fi set, split-level home, kitchen equipment. The very mechanism which ties the individual to his society has changed, and social control is anchored in the new needs which it has produced.” (From One-Dimensional Man)

Herbert Marcuse: “Liberating tolerance, then, would mean intolerance against movements from the Right, and toleration of movements from the Left.” (From “Repressive Tolerance“)

| Rationalization of political violence In his 1965 essay “Repressive Tolerance,” Herbert Marcuse argued that tolerance in advanced industrial societies, particularly under capitalism, is inherently repressive because it perpetuates oppression by granting equal platforms to both liberating (left-wing, viewed as progressive) ideas and oppressive (right-wing, viewed as regressive) ones. He proposed “liberating tolerance,” which involves active intolerance toward movements from the right while extending tolerance only to subversive, emancipatory forces from the left. This could include extralegal actions, propaganda, and even violence to shift power balances and prevent the dominance of what he saw as fascist tendencies inherent in conservative or capitalist structures. Marcuse justified this by framing right-wing ideologies as synonymous with fascism and Nazism, viewing them as extensions of historical domination (e.g., enlightenment rationality devolving into barbarism). He contended that violence from below—by the oppressed against oppressors—was redemptive and necessary for true liberation, distinguishing it from the systemic violence of the status quo. One of the main errors in his analysis, a consequence of his biases, is classifying Nazism and fascism as right-wing. Coupled with his flawed binary view—the left as inherently good and liberating, the right as evil and fascist—this provided a philosophical justification for asymmetrical tactics, including coercion and repression, without self-reflection on who actually had fascist and authoritarian tendencies. Historical and Modern Influences on Radical Left Violence Marcuse’s ideas profoundly shaped the New Left in the 1960s and 1970s, inspiring violent movements that targeted right-wingers accused of being fascists. As a key figure in the Frankfurt School, he influenced groups like Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), which escalated to building occupations and confrontations, and the Weather Underground, a militant offshoot that conducted bombings against government symbols, justifying them as resistance to “fascist” imperialism in Vietnam and domestic racism. Figures like Angela Davis (a student of Marcuse and affiliated with the Black Panthers) and Abbie Hoffman embodied this, championing armed self-defense and disruption as anti-fascist necessities. In modern contexts, Marcuse’s theses underpin groups like Antifa, which employ direct action—including physical violence, doxing (the malicious practice of collecting and publishing an individual’s private and personally identifiable information online without their consent), harassment, and property damage — against conservatives, often labeled as “Nazis” or “fascists”. For instance, during the 2020 George Floyd protests and subsequent riots, Antifa militants cited similar logic to rationalize attacks on police and right-wing gatherings as preemptive strikes against fascism, echoing Marcuse’s call for intolerance toward regressive forces (that is, conservatives, who oppose their worldview). This influence persists in radical left activism, where equating the right with historical evils like Nazism justifies “redemptive violence,” even though this actually reflects the totalitarian tactics Marcuse claimed to oppose, leading to cycles of escalating violence. |

Max Horkheimer: “A theory is critical insofar as it seeks to liberate human beings from the circumstances that enslave them.” (From “Traditional and Critical Theory.”)

Jürgen Habermas: “The difference between political terror and ordinary crime becomes clear during the change of regimes, in which former terrorists become well-regarded representatives of their country.” (From Philosophy in a Time of Terror: Dialogues with Habermas and Derrida)

Classification of Main Frankfurt School Authors in the Circular Diagram

Max Horkheimer

- Primary Group: Radical Leftists

- Rationale: As a foundational Frankfurt School director, Horkheimer’s work (e.g., co-authoring Dialectic of Enlightenment) advocates for radical transformation of society through critique of capitalism and enlightenment rationality, aligning with Radical Leftists’ focus on revolutionary change, anti-capitalism, and fundamental social restructuring. His Marxist roots and emphasis on emancipation via critical theory fit this group’s revolutionary ethos, though he shares some adjacency with Democratic Leftists in opposing outright violence.

Theodor Adorno

- Primary Group: Radical Leftists

- Rationale: Adorno’s critiques of the culture industry, authoritarianism (The Authoritarian Personality), and mass society in Dialectic of Enlightenment reflect a deep anti-capitalist stance calling for profound societal overhaul. This matches Radical Leftists’ traits of challenging established systems through intellectual revolution and opposing free markets, with overlaps to Radical Statists in analyzing totalitarian tendencies but ultimately rejecting them.

Herbert Marcuse

- Primary Group: Radical Leftists

- Rationale: Marcuse’s One-Dimensional Man critiques advanced capitalism’s integration of opposition, advocating a “Great Refusal” and radical liberation. His influence on the New Left and emphasis on revolutionary potential in marginalized groups align with Radical Leftists’ revolutionary means, anti-capitalism, and collectivist transformation, adjacent to Democratic Leftists in supporting some democratic elements but more extreme in rejecting the system wholesale.

Jürgen Habermas

- Primary Group: Democratic Leftists

- Rationale: As a second-generation thinker, Habermas shifts toward reformist ideals in The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere and The Theory of Communicative Action, emphasizing deliberative democracy, rational discourse, and social justice through institutional change rather than revolution. This fits Democratic Leftists’ values of redistribution, economic equality, and democratic governance via reform, with adjacency to Classical Liberals in valuing individual liberties and public debate, but rooted in leftist critique of systemic inequalities.

In the circular arrangement, the first-generation authors’ placements in Radical Leftists highlight their proximity to Democratic Leftists (shared opposition to free markets and focus on equality) and Radical Statists (analysis of domination), but their core opposition is to groups like Moderate Conservatives (tradition) and Classical Liberals (economic freedom). Habermas’s position in Democratic Leftists shows a milder adjacency to Radical Leftists (economic equality) and Classical Liberals (liberties), opposing Authoritarian Conservatives (hierarchy). This classification acknowledges the School’s evolution from radical critique to more pragmatic democratic theory, as per the diagram’s fluid continuum.

| The Marxist Intellectual Aristocracy There is another fundamental contradiction in contemporary critical theory: while it claims democratic goals, in practice it advocates a form of intellectual aristocracy based on specialized theoretical knowledge. The Problem of Intellectual Authority Frankfurt theorists confront what might be called a “paternalistic paradox”: they claim to know the “true interests” of workers better than they do. As noted about Marcuse, he questioned “who is qualified to make all these distinctions” about true versus false needs, responding that it would be those “in the maturity of their faculties”—essentially, he and his intellectual allies. This position exemplifies what critics identify as the intellectual arrogance characteristic of academic elites. Critical theory assumes that ordinary people suffer from “false consciousness” and need intellectual enlightenment to recognize their own oppression. The Contemporary Academic Aristocracy Modern academia effectively operates as a “silent aristocracy” where “access and authority are interlinked” and “intellectual control slowly gives way to new voices”. Marxist intellectuals position themselves as an enlightened vanguard capable of diagnosing the “false consciousness” of the masses, assuming superior epistemic authority. However, these groups serve their own interests while presenting themselves as advocates for workers. The Democratic Paradox of Critical Theory Critical theorists face an irresolvable contradiction: they defend democracy while systematically rejecting actual democratic choices when these don’t align with their theoretical prescriptions. This position reveals that their true defense is of an “aristocracy of critics” who determine what constitutes authentic versus false consciousness. |

Conclusion

Although the premises of the first generation of the Frankfurt School were fallacious and the results even worse, they remain influential in radical left academic circles. The second generation, Habermas, equally influential in academic circles, evolved toward more moderate leftist views (although retaining some utopian elements).

Questions for reflection

1. What methodological flaws have academic philosophers identified in the Frankfurt School’s approach to critique?

2. How does the Frankfurt School’s theory of “false consciousness” exemplify a form of intellectual paternalism, where academic theorists assume authority to determine which needs and desires of the masses are “authentic” versus “manipulated”?

3. How does the accusation of intellectual elitism against the first generation of the Frankfurt School relate to their distancing from the experiences of the popular masses?

4. In what ways have critics argued that Theodor Adorno’s critique of mass culture demonstrates an elitist disdain for popular tastes and ordinary people’s agency?

5. To what extent does the cultural pessimism of the first generation of the Frankfurt School about the masses’ capacity to recognize their own lack of freedom justify a new form of intellectual authoritarianism disguised as critical theory?

6. If an option doesn’t meet calculability and utility standards, is it still valid in a democracy? And if you reject an alternative that is more useful to you but offends your moral standards, are you acting illegally in a democracy? Or can you, using your free will, choose?

7. Who has the right to criticize your consumer choices? If you disagree with the critic, does that make you an alienated?

8. If you justify violence against political enemies you misrepresent as fascists, are you not a fascist-like?

9. The box below shows a huge left-wing bias between professores and journalists.

| College and University Professors Studies on the political affiliations of U.S. college and university professors consistently show a significant imbalance, with Democrats greatly outnumbering Republicans. The exact percentages vary by study, institution type, field, and methodology (e.g., self-identification vs. party registration), but ratios typically range from 5:1 to 12:1 Democrats to Republicans overall, with higher imbalances in humanities and social sciences (e.g., up to 12:1 in humanities). A national survey of faculty found 50% identifying as Democrats and 11% as Republicans (with 33% independent and 5% other). More recent analyses of party registration at elite liberal arts colleges show ratios around 10:1 among registered faculty, translating to roughly 55% Democrats and 5% Republicans overall (with the remainder independent, unregistered, or other) (https://www.washingtontimes.com/news/2018/apr/26/democratic-professors-outnumber-republicans-10-to-/). Journalists The most recent national survey of U.S. journalists (from 2022) found that 36% identify as Democrats, while only 3.4% identify as Republicans (with 51.7% independent and the rest other). This represents a continued decline in Republican identification, down from 7.1% in 2013 and 18% in 2002 (https://www.washingtontimes.com/news/2023/dec/30/only-34-us-journalists-are-republicans-survey/). |

This pattern reflects on the coverage in favor or against republicans and democrats candidates.

| Recent Coverage During Trump’s 2025 Presidency Analyses of major broadcast networks (ABC, CBS, NBC) during the first 100 days of Trump’s second term in 2025 found overwhelmingly negative coverage. One study reported 92% negative evaluations of Trump’s actions and statements, with only 8% positive. (https://abc3340.com/news/nation-world/major-networks-92-negative-coverage-of-president-trump). 2024 Election Campaign Coverage During the 2024 presidential race, network evening news coverage (ABC, CBS, NBC) was highly imbalanced (https://x.com/SecretsBedard/status/1850916790131376261) Trump: 85% negative, 15% positive. Harris: 78% positive, 22% negative. |

9.1. Is the problem the false consciousness of the working class or the refusal of left-wing intellectuals to accept that their proposals and candidates are, in fact, bad?

9.2. What should we think of someone who loses an election and, instead of trying to understand his failures, returns to vilifying those who voted against him (a bunch of deplorables, fascists, alienated people, nazi, etc.)?

9.3. Is using universities and colleges to conduct a biased survey accusing conservative Americans of being fascists or publishing a book claiming the decline of democracy in the face of the election of someone you dislike a good path? Is it an acceptable path? Is this serious science?

10. If the Frankfurt School authors were anti-fascist in principle, what justifies their appropriation and defense of fascist techniques to attack conservatives (or was this fight merely a feud between twin brothers)?

Leave a comment