Historical Context

Born in 1818 in Trier, Prussia, Karl Marx, along with Friedrich Engels, developed a body of ideology known as Marxism. This includes his economic critiques in Capital (1867–1894) and the revolutionary call for action in The Communist Manifesto (1848). Marx’s “scientific” socialism has its roots in historical materialism, a method that analyzes social development through economic conditions, distinguishing it from the “idealistic utopian socialism” of thinkers such as Saint-Simon and Fourier. This approach sought to distance socialism from traditional concepts such as justice or the common good (considered without material concreteness, merely part of the ideology of the ruling class), claiming to be based solely on material phenomena and observable economic laws, and thus market itself as something scientific.

| Socialists are against the exploitation of workers by capitalists, but they believe they can freely exploit whoever they want. Paul Bede Johnson (1928 –2023) was a British journalist, historian, speechwriter and author. In his book “Intellectuals: From Marx and Tolstoy to Sartre and Chomsky” he wrote: (…) In all his researches into the iniquities of British capitalism, he came across many instances of low-paid workers but he never succeeded in unearthing one who was paid literally no wages at all. Yet such a worker did exist, in his own household … This was Helen Demuth [the life-long family maid]. She got her keep but was paid nothing … She was a ferociously hard worker, not only cleaning and scrubbing, but managing the family budget … Marx never paid her a penny … In 1849-50 … [Helen] became Marx’s mistress and conceived a child … Marx refused to acknowledge his responsibility, then or ever, and flatly denied the rumors that he was the father… [The son] was put out to be fostered by a working-class family called Lewis but allowed to visit the Marx household [to see his mother]. He was, however, forbidden to use the front door and obliged to see his mother only in the kitchen. Marx was terrified that [the boy’s] paternity would be discovered and that this would do him fatal damage as a revolutionary leader and seer … [Marx] persuaded Engels to acknowledge [the boy] privately, as a cover story for family consumption. But Engels … was not willing to take the secret to the grave. Engels died, of cancer of the throat, on 5 August 1895; unable to speak but unwilling that Eleanor [one of Marx’s daughters] should continue to think her father unsullied, he wrote on a slate: ‘Freddy [the boy’s name] is Marx’s son … |

Economistic Characteristics

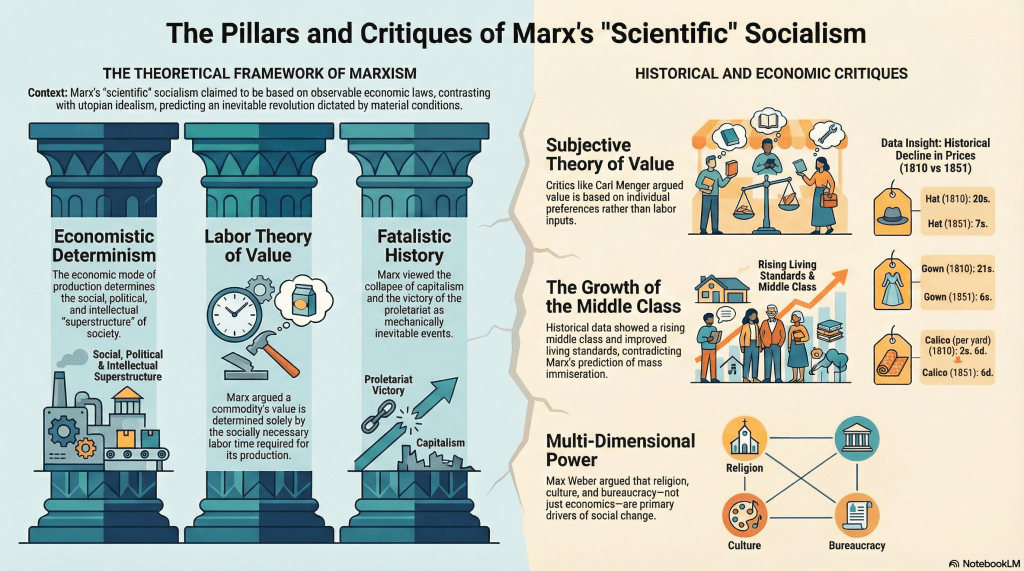

Marx’s analysis of the free market system (which he calls capitalism) is profoundly economistic, focusing on the economic structure as the true foundation of society. He postulated that the mode of production, comprising the material forces of production (technology, labor) and the relations of production (class relations), determines the social, political, and intellectual superstructure. For example, in capitalism, the bourgeoisie owns the means of production (and thus determines culture, morality, and ideology), while the proletariat sells its labor power, leading to exploitation through surplus value—the difference between the value produced by workers and their wages.

Figure 20. Karl Marx

Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Karl_Marx_001_restored.jpg

The basis for his economistic view is his labor theory of value. Marx argued that the value of a commodity is rooted in the labor required to produce it, specifically the “socially necessary labor time” (the average time needed under normal production conditions). According to him, this is an objective measure, tying value to labor input, as seen in Capital, Volume 1: “The value of a commodity is determined by the quantity of socially necessary labour-time“.

| Subjective theory of value Carl Menger’s (1840-1921) revolutionary subjective theory of value fundamentally challenged classical economics by arguing that value originates from individual preferences rather than labor inputs. His 1871 work “Principles of Economics” it: “When I discussed the nature of value, I observed that value is nothing inherent in goods and that it is not a property of goods. But neither is value an independent thing. There is no reason why a good may not have value to one economizing individual but no value to another individual under different circumstances. The measure of value is entirely subjective in nature, and for this reason a good can have great value to one economizing individual, little value to another, and no value at all to a third, depending upon the differences in their requirements and available amounts. What one person disdains or values lightly is appreciated by another, and what one person abandons is often picked up by another.” |

Mechanistic and Fatalistic Dimensions

Marx’s historical materialism suggests a mechanistic view of societal development, where changes in the economic base inevitably lead to changes in the superstructure. He believed history progresses through stages—primitive communism, slavery, feudalism, capitalism, socialism, and communism—driven by the development of productive forces and the contradictions within each mode. This deterministic process is mechanistic, as it implies societal change follows predictable economic laws, akin to a machine. For example, capitalism’s internal contradictions, such as overproduction and class conflict, are seen as mechanically leading to its collapse.

This view also carries a fatalistic element, as Marx argued that the transition to socialism is inevitable. In The Communist Manifesto, he and Engels state that “the fall of the bourgeoisie and the victory of the proletariat are equally inevitable,” reflecting a belief that historical processes, independent of human will, will lead to socialism. This fatalism is further supported by his 1859 Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy, where he suggests relations of production are indispensable and lead to inevitable historical development.

| On Marx’s Mechanistic Economic Materialist View Max Weber (1864–1920), a foundational figure in sociology, engaged critically with Karl Marx’s economicistic views, particularly his materialist conception of history and economic determinism. While Weber recognized the importance of economic factors, he argued that Marx’s focus on class struggle and material conditions as the primary drivers of societal change was overly reductive. Weber’s critiques of Marx’s economic theories, particularly as articulated in The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism (1905) and Economy and Society (1922), center on several key points: Overemphasis on Economic Determinism: Marx’s historical materialism posits that economic conditions (the mode of production) determine the social, political, and cultural superstructure. Weber argued this was too simplistic, as non-economic factors like ideas, religion, and culture also shape history. Role of Religion and Culture: Weber argued that Marx underestimated the role of religious and cultural values in economic development. In The Protestant Ethic, he proposed that the Protestant work ethic, particularly Calvinism, fostered the “spirit of capitalism” by encouraging hard work and rational economic behavior, independent of purely economic forces. Neglect of Bureaucracy and Rationalization: Marx focused on class conflict and the labor-capital dynamic, but Weber emphasized the rise of bureaucracy and rationalization as key features of modern capitalism. He argued that Marx’s analysis ignored the growing importance of formal organizations and legal-rational authority. Limited View of Class and Power: Marx defined class primarily in economic terms, based on ownership of the means of production. Weber introduced a multidimensional view of power, incorporating status (social prestige) and party (political influence) alongside class, arguing that social stratification is not solely economic. Ideal Types vs. Historical Materialism: Weber developed the concept of “ideal types” to analyze social phenomena, rejecting Marx’s deterministic view that history follows a predictable path driven by economic stages. Weber saw history as more contingent, shaped by a complex interplay of factors. |

Revolutionary Imperative

A defining feature of Marx’s scientific socialism is its revolutionary character. Marx rejected reformist approaches, advocating for a proletarian revolution to overthrow capitalism. He believed that the working class, exploited under capitalism, would rise up to “expropriate the expropriators,” seizing control of the means of production to establish a classless society. This revolutionary stance is articulated in The Communist Manifesto, where he calls for the abolition of private property and the establishment of collective ownership. This revolutionary approach contrasts with gradualist socialism and underscores Marx’s belief that systemic change requires a fundamental rupture.

| What is a revolution ? Socialists like to claim that Karl Marx was a humanist. A quote attributed to Mao Zedong explains what being a humanist mean to the radical left: “A revolution is not a dinner party, or writing an essay, or painting a picture, or doing embroidery; it cannot be so refined, so leisurely and gentle, so temperate, kind, courteous, restrained and magnanimous. A revolution is an insurrection, an act of violence by which one class overthrows another.” |

Unplanned Approach to Socialism

Marx’s socialism is often described as unplanned, as he deliberately refrained from providing detailed blueprints for the future communist society. He famously stated that he would not write “recipes” for the “restaurants” of the future, indicating his focus on critiquing capitalism rather than designing socialism. This approach stems from his belief that satisfactory solutions to social problems would emerge automatically from the historical process, driven by the material conditions and class struggles of the time. Marx said very little about how socialism would be implemented post-revolution.

| Communism: the new religion founded by Marx and his apostles John Maynard Keynes (1883 –1946), was an English economist. Despite being a leftist (but not a radical), in 1925 he wrote about Leninism, the first implementation of Karl Marx’s ideas: (i) What is the Communist Faith? Leninism is a combination of two things which Europeans have kept for some centuries in different compartments of the soul—religion and business. We are shocked because the religion is new, and contemptuous because the business, being subordinated to the religion instead of the other way round, is highly inefficient. Like other new religions, Leninism derives its power not from the multitude but from a small minority of enthusiastic converts whose zeal and intolerance make each one the equal in strength of a hundred indifferentists.(…) Like other new religions, it persecutes without justice or pity those who actively resist it. Like other new religions, it is unscrupulous. Like other new religions, it is filled with missionary ardour and occumenical ambitions. But to say that Leninism is the faith of a persecuting and propagating minority of fanatics led by hypocrites is, after all, to say no more nor less than that it is a religion and not merely a party, and Lenin a Mahomet, not a Bismarck. (…). For he believes in two things: the introduction of a New Order upon earth, and the method of the Revolution as the only means thereto. The New Order must not be judged either by the horrors of the Revolution or by the privations of the transitionary period. The Revolution is to be a supreme example of the means justified by the end. The soldier of the Revolution must crucify his own human nature, becoming unscrupulous and ruthless, and suffering himself a life without security or joy—but as the means to his purpose and not its end. (The full text can be read at https://www.economicsnetwork.ac.uk/archive/keynes_persuasion/A_Short_View_of_Russia.htm) |

Main Ideas in The Communist Manifesto

The Communist Manifesto is a concise pamphlet outlining the principles of communism. Written for the Communist League, it explains the main concepts behind communism and proposes an agenda for the party to implement once it comes to power. It includes:

- Historical Materialism and Class Struggle:

- Marx opens with the famous line: “A spectre is haunting Europe — the spectre of communism,” declaring that “the history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles”. Societies are defined by the relationship to the means of production, with new dominant classes emerging at each stage (e.g., primitive communism, antiquity, feudalism, capitalism).

- Capitalism is marked by the exploitation of the proletariat by the bourgeoisie, who own the means of production and constantly revolutionize production and social relations, creating a “world after its own image”

- Critique of Capitalism:

- Capitalism ensures humans are stunted and alienated, polarizing and unifying the proletariat, leading to its own destruction via revolution. It is a global system that expands markets but creates conditions for its collapse due to internal contradictions.

- Revolutionary Change and Emergence of Communism:

- Marx predicts a proletarian revolution will overthrow capitalism, leading to communism, a classless society where “the free development of each is the condition for the free development of all”. This involves transitional policies, such as:

- Abolition of property in land and application of all rents of land to public purposes.

- A heavy progressive or graduated income tax.

- Abolition of all rights of inheritance.

- Confiscation of the property of all emigrants and rebels.

- Centralisation of credit in the hands of the state, by means of a national bank with State capital and an exclusive monopoly.

- Centralisation of the means of communication and transport in the hands of the State.

- Marx predicts a proletarian revolution will overthrow capitalism, leading to communism, a classless society where “the free development of each is the condition for the free development of all”. This involves transitional policies, such as:

- Role of Communists and Internationalism:

- Communists express the general will of the proletariat, defending their shared interests globally, independent of nationalities, and not opposing other working-class parties. The Manifesto ends with the slogan “Workers of the world, unite! You have nothing to lose but your chains,” emphasizing the international character of Marxist ideas.

- Critique of Other Socialisms:

- Marx distinguishes communism from Reactionary Socialism (Feudal, Petty-Bourgeois Socialism), Conservative or Bourgeois Socialism, and Critical-Utopian Socialism, dismissing them for reformism and failing to recognize the proletariat’s revolutionary role

Main Ideas in Das Kapital

Das Kapital, published in three volumes, is a detailed critique of political economy, analyzing the economic structures of the free market system (which he calls capitalism). However, only the first volume was published during Marx’s lifetime. Supposedly scientific, its main ideas include:

- Historical Materialism and Capitalism:

- Marx examines capitalism as a historical epoch, tracing its origins, development, and inevitable decline due to internal contradictions.

- Labor Theory of Value and Surplus Value:

- Central to Marx’s theory is the labor theory of value, where a commodity’s value is determined by the socially necessary labor time required for its production. Capitalists extract surplus value—the difference between the value workers produce and their wages—leading to exploitation.

- Commodity Fetishism and Alienation:

- Marx describes commodity fetishism, where capitalist markets obscure social relationships, making them appear as relations between things. This is linked to alienation, where workers are estranged from their labor, products, and humanity, a concept foundational to his critique.

- Tendency of the Rate of Profit to Fall and Crisis Theory:

- Marx argues capitalism is unstable due to the tendency of the rate of profit to fall, leading to cyclical economic crises, including overproduction, underconsumption, and financial instability. These crises are inherent, not accidental, and contribute to capitalism’s eventual collapse.

- Exploitation and Class Analysis:

- The exploitation of the proletariat is foundational to conflict theory, class analysis, and the study of social stratification and historical change. It highlights the antagonistic relationship between capitalists and workers, driving class struggle.

- Volume Structure:

- Volume I (1867): Focuses on the production process and labor exploitation, detailing how surplus value is generated.

- Volume II (1885): Examines capital circulation and the causes of economic crises, such as overproduction and underconsumption.

- Volume III (1894): Explores the distribution of surplus value among economic actors, like industrialists, landlords, and financiers, and the equalization of profit rates.

- Scientific Critique and Influences:

- Das Kapital is presented as a scientific work, synthesizing classical political economy (e.g., Adam Smith, David Ricardo), German critical philosophy (e.g., Hegel), and utopian socialism (e.g., Fourier, Proudhon). It critiques bourgeois economists who argue capitalism is efficient and stable, showing instead its exploitative and crisis-prone nature.

- Additional Concepts:

- Marx introduces concepts like ideology, hegemony, reification, and critique of power, impacting fields like sociology, political science, philosophy, and cultural studies.

Marx’s Failed Analysis and Predictions

Marx’s most significant predictions and theoretical claims have been contradicted by historical experience and empirical research. The labor theory of value has been abandoned by mainstream economics in favor of more sophisticated theories that account for subjective preferences and complex production relationships. Revolutionary predictions failed to materialize in the expected locations and forms, while economic development has generally improved rather than worsened living standards for workers in developed countries.

The internal inconsistencies identified by critics, combined with the unfalsifiable nature of Marx’s dialectical method, suggest that Marxism functions more as an ideological framework than as a scientific theory capable of generating accurate predictions about social development. While Marx’s analysis of capitalism’s tendency toward inequality and crisis contains valuable insights, his solutions and predictions about revolutionary transformation have proven unrealistic given the complexity of modern social and economic systems.

| London Labour and the London Poor Although Marx did not observe the increase in the number of people in the middle class and the improvement in the conditions of this class (on the contrary, his theory denied this), some contemporary authors did. This is the case of Henry Maythew. Henry Maythew’s London Labour and the London Poor highlights the growth and cultural dominance of the British middle class during the mid-nineteenth century through shifts in consumer habits, the professionalization of domestic life, and the expansion of the literary market. The following excerpts demonstrate different aspects of this growth: Economic Expansion and Improved Access to Goods The text notes a significant decrease in the cost of manufactured goods between 1810 and 1851, which allowed a broader portion of the population to adopt middle-class standards of dress and living. • “The price of a hat in 1810 was 20s., and in 1851 it had fallen to 7s.;—or if a labourer’s weekly wage had been paid for in hats, he would have had three times as great a supply in the present year as he had forty years ago. A gown cost 21s. in 1810, and only 6s. in 1851. Calico was 2s. 6d. a yard against 6d. at present.” The Formalization of Middle-Class Domesticity The rise of the middle class was accompanied by the professionalization of the home, as seen in the popularity of guides for domestic management and the accumulation of specific household items. • “The first edition of Mrs Beeton’s Book of Household Management (1861) is full of money-saving tips for the frugal housewife; it also provides a list… intended to show ‘the articles required for the kitchen of a family in the middle class of life’.“ • “From ‘1 Tea-kettle’ (6s. 6d.) to ‘I Wood Meat-screen’ (30s.), the list comprises 37 items, at a total cost of £8 11s. 1d., with the reminder that Messrs. Slack publish ‘a useful illustrated catalogue … which it will be found advantageous to consult by those about to furnish’.” Expansion of the Literary and Professional Market The growth of the middle class created a massive new audience for literature and journalism, as more people had the time and literacy to read about their own society. • “As London continued to expand… more people than ever before wanted to read about each other and themselves, and the books and journals that set out to meet this need were at once mirrors of contemporary life and barriers against its worst excesses.“ • “Few writers of the early Victorian period so perfectly sum up its atmosphere of nervous ambition, in which clever young men (and, more rarely, women) turned themselves into pens for hire, roaming the streets of literary London in search of the right formula to bring them money and fame.” Cultural and Social Indicators The presence of a substantial middle class is also reflected in the types of entertainment and services they supported, as well as the social satire directed at them. • “The middle class of society are our best supporters [of ‘Happy Families’ animal exhibitions].” • “Whom to Marry and How to Get Married! (1848) offered a genial but blunt satire on middle-class sexual morality.” |

Contemporary social science has developed more nuanced approaches to understanding inequality, social conflict, and economic development that incorporate insights from Marx while avoiding his deterministic assumptions and failed predictions. The persistence of capitalist systems, their adaptation to address some of the problems Marx identified, and the development of democratic institutions for managing social conflict suggest that social change occurs through more complex and gradual processes than Marx’s revolutionary framework anticipated.

| Böhm von Bawerk prediction on socialism Eugen Böhm Ritter von Bawerk (1851 –1914) was as Austrian Economist. Follower of the STV, he concludes about Marx’s work: What will be the final judgment of the world? Of that I have no manner of doubt. The Marxian system has a past and a present, but no abiding future. Of all sorts of scientific systems those which, like the Marxian a hollow dialectic, are based on a hollow dialectic, most surely doomed. A clever dialectic may make a temporary impression on the human mind, but cannot make a lasting one. In the long run facts and the secure linking of causes and effects win the day. In the domain of natural science such a work as Marx’s would even now be impossible. In the very young social sciences it was able to attain influence, great influence, and it will probably only lose it very slowly, and that because it has its most powerful support not in the convinced intellect of its disciples, but in their hearts, their wishes, and their desires. It can also subsist for a long time on the large capital of authority which it has gained over many people. In the prefatory remarks to this article I said that Marx had been very fortunate as an author, and it appears to me that a circumstance which has contributed not a little to this good fortune is the fact that the conclusion of his system has appeared ten years after his death, and almost thirty years after the appearance of his first volume. If the teaching and the definitions of the third volume had been presented to the world simultaneously with the first volume, there would have been few unbased readers, I think, who would not have felt the logic of the first volume to be somewhat doubtful. Now a belief in an authority which has been rooted for thirty years forms a bulwark against the incursions of critical knowledge—a bulwark that will surely but slowly be broken down. (…) |

Connection to the Diagram of Political Mindsets

Karl Marx is classified as a Socialist in the Circular Diagram of Western Political Mentalities, positioned at the core of the Socialist segment. His revolutionary vision of a classless, communist society, rooted in class struggle and the abolition of private property, aligns with socialist principles of collective equality and systemic overhaul. Unlike Fourier, Saint-Simon, and Owen, whose utopian socialism includes reformist or individualistic elements, Marx’s scientific socialism is uncompromisingly revolutionary, distancing him from the Socialist–Social Democrat boundary. This placement reflects his radical and systematic approach, as analyzed in the context of the circular diagram.

Key quotes

Class Struggle

- “The history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles.“

Source: The Communist Manifesto (1848), co-authored with Friedrich Engels. - “Let the ruling classes tremble at a Communistic revolution. The proletarians have nothing to lose but their chains. They have a world to win.”

Source: The Communist Manifesto (1848), co-authored with Friedrich Engels.

Materialism and Ideology

- “The mode of production of material life conditions the social, political and intellectual life process in general. It is not the consciousness of men that determines their being, but, on the contrary, their social being that determines their consciousness.“

Source: A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy (1859). - “The ideas of the ruling class are in every epoch the ruling ideas, i.e. the class which is the ruling material force of society, is at the same time its ruling intellectual force.”

Source: The German Ideology (1845), co-authored with Friedrich Engels. - “The production of ideas, of conceptions, of consciousness, is at first directly interwoven with the material activity and the material intercourse of men, the language of real life.“

Source: The German Ideology (1845), co-authored with Friedrich Engels.

Alienation and Labor

- “The fact that labour is external to the worker, i.e., it does not belong to his intrinsic nature; that in his work, therefore he does not affirm himself but denies himself, does not feel content but unhappy, does not develop freely his physical and mental energy but mortifies his body and his mind.”

Source: Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844 (1844). - “The less you are, the less you express your own life, the more you have, i.e., the greater is your alienated life, the greater is the store of your estranged being.“

Source: Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844 (1844).

Capitalism and Exploitation

- “Capital is dead labour, that, vampire-like, only lives by sucking living labour, and lives the more, the more labour it sucks.“

Source: Capital, Volume I (1867). - “The worker’s existence is thus brought under the same condition as the existence of every other commodity. The worker has become a commodity, and it is a bit of luck for him if he can find a buyer, And the demand on which the life of the worker depends, depends on the whim of the rich and the capitalists.“

Source: Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844 (1844). - “The hand-mill gives you society with the feudal lord; the steam-mill society with the industrial capitalist.”

Source: The Poverty of Philosophy (1847).

Communism and Revolution

- “In place of the old bourgeois society, with its classes and class antagonisms, we shall have an association in which the free development of each is the condition for the free development of all.“

Source: The Communist Manifesto (1848), co-authored with Friedrich Engels. - “The philosophers have only interpreted the world, in various ways; the point is to change it.”

Source: Theses on Feuerbach (1845). - “Communism … is the genuine resolution of the antagonism between man and nature and between man and man; it is the true resolution of the conflict between existence and essence, objectification and self-affirmation, freedom and necessity, individual and species.”

Source: Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844 (1844). - “In a higher phase of communist society, after the enslaving subordination of the individual to the division of labor, and therewith also the antithesis between mental and physical labor, has vanished; after labor has become not only a means of life but life’s prime want; after the productive forces have also increased with the all-around development of the individual, and all the springs of co-operative wealth flow more abundantly—only then can the narrow horizon of bourgeois right be crossed in its entirety and society inscribe on its banners: From each according to his ability, to each according to his needs!“

Source: Critique of the Gotha Programme (1875).

Religion

- “Religious suffering is, at one and the same time, the expression of real suffering and a protest against real suffering. Religion is the sigh of the oppressed creature, the heart of a heartless world, and the soul of soulless conditions. It is the opium of the people.”

Source: Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right (1843).

| The Social Doctrine of the Roman Catholic Church In his encyclical “Rerum Novarum” (1891), a fundamental document of the Social Doctrine of the Church, which addresses the conditions of the working class and the relationship between capital and labor during the Industrial Revolution, Pope Leo XIII stated: “5.(…) Socialists, therefore, by endeavoring to transfer the possessions of individuals to the community at large, strike at the interests of every wage-earner, since they would deprive him of the liberty of disposing of his wages, and thereby of all hope and possibility of increasing his resources and of bettering his condition in life. 6. (…) And on this very account – that man alone among the animal creation is endowed with reason – it must be within his right to possess things not merely for temporary and momentary use, as other living things do, but to have and to hold them in stable and permanent possession; he must have not only things that perish in the use, but those also which, though they have been reduced into use, continue for further use in after time. “ (https://www.vatican.va/content/leo-xiii/en/encyclicals/documents/hf_l-xiii_enc_15051891_rerum-novarum.html) |

Final considerations

The “scientific” ideas of Karl Marx, although essentially mistaken in all their economic aspects, remain alive in political thought, influencing radical left-wing movements worldwide, thanks to concepts he engendered, such as surplus value, fetishism, alienation, and exploitation. Such concepts are the basis that allows the leadership of the radical left to culturally control its base, making any reflection on reality unnecessary, simply framing it in simplified explanations (almost always substantially wrong), but which give the impression that its cadres have useful proposals (almost always inconsequential, but which signal some form of moral virtue even when they evidently cause harm to those who the socialists say they want to help) or that they have something relevant to say.

| Was Marx so committed to his theories that he refused to see the facts? Marx had access to evidence that didn’t align perfectly with some of his predictions, yet he maintained his theoretical framework. He was aware of developments that seemed to contradict certain aspects of his theory, such as: – The growth of the middle class in industrialized countries like England and America, rather than its disappearance as his theory of class polarization might suggest. – The improving conditions for some segments of the working class, contrary to his prediction of increasing immiseration. – The persistence and adaptability of capitalism, despite the crises he identified. However, Marx interpreted these contradictions within his dialectical framework, often viewing them as temporary phenomena or as manifestations of capitalism’s internal contradictions that would eventually lead to its collapse. Marx was primarily working within a theoretical tradition that emphasized long-term historical processes and systemic analysis. He was less concerned with short-term empirical discrepancies, which he might have viewed as merely temporary deviations from the underlying historical trajectory he had identified. It’s also worth noting that Marx continuously revised his work and left much of it incomplete, suggesting he was grappling with these contradictions. The fact that he only published the first volume of “Capital” during his lifetime, despite working on the project for decades, indicates he may have been struggling to reconcile certain aspects of his theory with empirical reality. |

Questions for reflection

1. Marx’s life and conduct suggest a typical characteristic of the socialist mentality: what they demand of others does not apply to them (hypocrisy). How do personal contradictions in the lives of radical leftists like Marx affect your perception of and credibility in their theories, proposals, and actions?

2. Consider the religious struggle between Islam and Western civilization (a Judeo-Christian civilization), which has lasted for about 14 centuries. Is the history of all societies existing today a history of class struggle?

3. How much labor is crystallized in a cup of glass?

3. How much does a television value? How much does it value for you?

4. Consider the quality of life before and now under capitalism. Have capitalists appropriated all the surplus?

5. Is a historical reduction in the rate of profit, suggesting its collapse, observable under capitalism?

6. In what ways do Marx’s critiques of capitalism remain relevant or outdated in light of contemporary economic developments and global capitalism?

7. How many people do you think a communist is willing to kill to implement a system that no one knows what it will be (in fact, we know), but which was promised as paradise on Earth? Considering your answer, what else do you think he is willing to do?

8. Is fetishism a material phenomenon?

9. Consider the evidence of the diverse growth of the British middle class and the improvement in their quality of life already perceptible in Marx’s time (some cited in this text). What led him to ignore the facts? What kind of “science” did he intend to construct?

Leave a comment