Introduction

John Rawls’ theory of justice as fairness is one of the most important contributions to 20th-century political philosophy, providing a conceptual framework that seeks to reconcile individual freedom with social equality through rationally derived principles. Rawls developed a contractual approach using the thought experiment of the “original position” and the “veil of ignorance” to derive two fundamental principles of justice: the principle of equal liberty and the difference principle. Together, these principles were intended to form the foundation of a just liberal democratic society. His work profoundly influenced contemporary moderate leftist political thought and can be classified within the spectrum of modern social liberalism, positioning itself as an alternative to both utilitarianism and extreme libertarianism.

Figure 25: John Rawls.

Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:John_Rawls_(1971_photo_portrait).jpg

Historical Context and Intellectual Foundations

The publication of “A Theory of Justice” in 1971 marked a resurgence of interest in the philosophical foundations of political liberalism. Rawls’ work emerged in response to the perceived limitations of utilitarianism as a theory of justice, particularly its inability to protect fundamental individual rights when they conflicted with the aggregate welfare of the majority.

Rawls observed that a necessary condition for justice in any society is that each individual should be an equal bearer of certain rights that cannot be disregarded under any circumstances, even if doing so would promote overall welfare or satisfy the demands of a majority. This fundamental observation led him to reject utilitarianism as an inadequate theory of justice, as this ethical theory would endorse forms of government where the greatest happiness of a majority would be achieved through the neglect of the rights and interests of a minority.

| A complex theory to replace basic Judeo-Christian values John Rawls was an atheist. He lost his Christian faith during his service as an infantryman in World War II, particularly after witnessing the horrors of war, the atomic bombing of Hiroshima, and the subsequent events on the battlefield. Although his early adult life was shaped by a conventional religious upbringing, and his undergraduate thesis was theological, his experiences in the war led him to abandon his religious beliefs and become an atheist upon leaving the army. His theory is clear evidence of what happens when the Judeo-Christian traditions of Western civilization are lost. For a Christian or for a Jew (or even for someone who is not, but understands the relevance of these traditions as fundamental principles of Western civilization), these limits to utilitarianism are clear. No one, including the state, can violate God-given and natural rights. And society’s belief in these values is the best protection anyone can have against state abuses. But, as an atheist, he had to seek a secular philosophical basis for justice that would protect minorities. A complex philosophical justification with extremely controversial premises and conclusions and limited acceptance, as will be developed later. |

Rawls’ approach was deeply influenced by the contractual tradition, drawing inspiration from thinkers such as Thomas Hobbes, John Locke, and Jean-Jacques Rousseau, each of whom used similar “starting points” (the state of nature) to explore political ideas. However, Rawls innovated significantly by developing the concept of original position as a representational device from which to derive his principles of justice.

The Theory of Justice as Fairness: Core Components

Rawls’ intellectual project aimed to solve the fundamental problem of how to have both freedom and equality in society, not simply by balancing them, but by demonstrating that freedom and equality could work together. This ambitious synthesis is what he called “justice as fairness,” a conception that seeks to treat all citizens with equal consideration and respect while allowing inequalities that improve everyone’s situation.

Rawls’ theory is based on the premise that a just society is one whose main political, social, and economic institutions, taken together, satisfy two fundamental principles that would be rationally chosen by individuals under conditions of impartiality. These principles emerge from a rational deliberative process conducted under what Rawls called the “original position,” a hypothetical state of choice in which individuals are ignorant of their particular position in society.

The structure of Rawls’ theory recognizes that brute luck is so completely intertwined with the contributions a person makes to their own success or failure that it is impossible to distinguish what people are responsible for from what they are not. Given this fact, Rawls argues that the only plausible justification for inequality is that it serves to make everyone better off, especially those who have less.

Rawls seeks to accommodate his theory of justice to what he considers to be the important fact that reasonable people deeply disagree about the nature of morality and the good life and will continue to do so in any non-tyrannical society that respects freedom of expression. He aims to make his theory evasive on these controversial issues and postulate a set of principles of justice that, he claims, all reasonable people can accept as valid, despite their disagreements.

The Original Position and the Veil of Ignorance

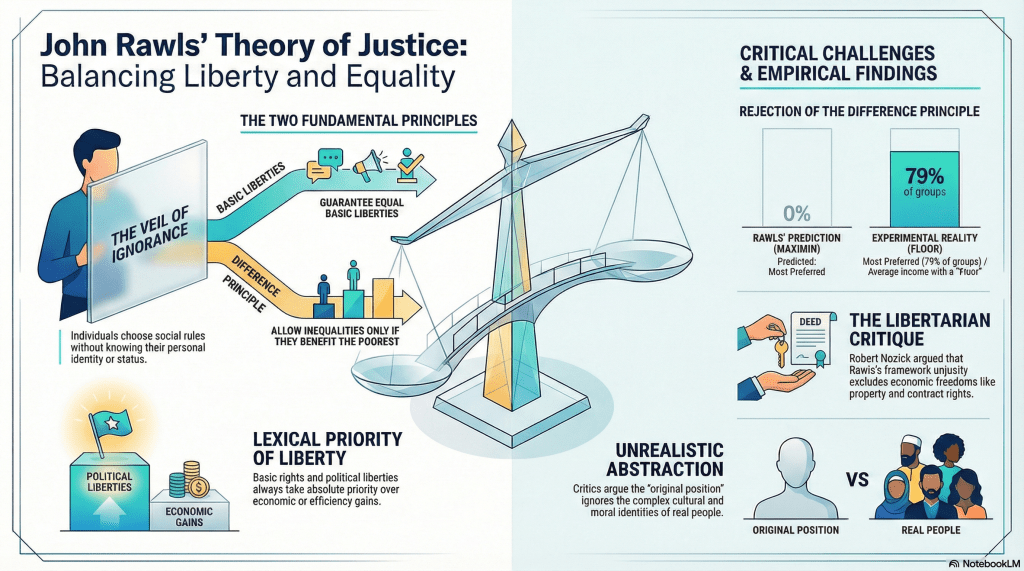

The thought experiment of the original position represents one of Rawls’ most significant innovations in modern political philosophy. This conceptual device imagines a group of people who must agree on the political and economic rules for a society in which they will live, but each person is behind a “veil of ignorance” that prevents them from knowing anything about themselves.

In the original position, individuals do not know their gender, race, age, intelligence, wealth, abilities, education, or religion. The only thing they know is that they are capable of participating in society. Rawls argued that people in this original position would know two things about themselves: first, that they can form and change their ideas about what constitutes a good life; second, that they can develop a sense of justice and desire to follow it.

The veil of ignorance ensures that no one would suggest unjust rules, such as saying that women or black people cannot hold public office, because they would not know if they themselves would be a woman or a black person. It would be illogical to propose something that could harm them. This logic leads to the difference principle: if you do not know your position in society, you would want to improve the lives of the worst-off people because you might end up being one of them.

The original position serves as a construction procedure that models what we consider to be fair conditions under which representatives of free and equal citizens are to specify the terms of social cooperation in the case of the basic structure of society. The veil of ignorance is a condition on arguments for principles of justice, ensuring that the principles chosen are those that rational people would choose when situated impartially.

This procedural mechanism allows Rawls to derive substantive principles of justice through a process that is both rational and impartial. Individuals in the original position, being rational and interested in promoting their own well-being, but not knowing what their position in the resulting society will be, will choose principles that protect everyone’s interests, especially those of the least advantaged.

| Criticism of the Original Position Critics of John Rawls’ original position have raised several key objections: – Unrealistic Abstraction: Some argue that the original position, with its veil of ignorance, is too abstract and detached from real-world conditions. Critics claim it oversimplifies human motivations and ignores the complexities of actual societal and economic contexts. – Rationality Assumptions: The model assumes that individuals in the original position are purely rational and self-interested, prioritizing their own benefit without any altruistic or communal considerations. Critics suggest this assumption may not accurately reflect human behavior. – Cultural and Moral Neutrality: The framework’s attempt to be neutral regarding cultural and moral values has been criticized for potentially neglecting important cultural differences and moral intuitions that might influence individuals’ perspectives on justice. – Epistemic Limitations: Some critics argue that individuals behind the veil of ignorance might not have enough information to make informed decisions about principles of justice, as they lack knowledge of their own preferences and societal contexts. – Limited Applicability: Critics point out that the principles derived from the original position might not be applicable or effective in non-ideal or non-liberal societies where different values and norms prevail. |

The Two Principles of Justice

From the original position, Rawls derived two fundamental principles of justice that he argues would be unanimously chosen by rational individuals under the veil of ignorance. The first principle, known as the principle of liberty, states that each person is to have an equal right to the most extensive system of equal basic liberties compatible with a similar system of liberty for all.

The basic liberties mentioned in the first principle comprise most of the rights and liberties traditionally associated with liberalism and democracy: freedom of thought and conscience, freedom of association, the right to representative government, the right to form and join political parties, the right to personal property, and the rights and liberties necessary to ensure the rule of law.

Notably, economic rights and liberties, such as freedom of contract or the right to own means of production, are not among the basic liberties as Rawls conceives them. This is because Rawls prioritizes liberties that guarantee political equality and individual autonomy in a context of justice, while economic issues (such as the distribution of resources or productive property) are primarily addressed by the second principle.

| Personal Preference Bias Rawls’s choice to include certain freedoms (such as freedom of thought, association, and political rights) as “basic” while excluding economic freedoms (such as unrestricted freedom of contract or ownership of the means of production) reflects an ideological bias, aligned with a liberal egalitarian vision that privileges distributive justice over a more libertarian or economically liberal conception of liberalism. This criticism can be articulated from several perspectives: Libertarian perspective: Philosophers such as Robert Nozick argue that excluding economic freedoms, such as the unrestricted right to property or freedom of contract, underestimates the importance of individual autonomy in the economic realm. For libertarians, property and freedom of contract are as fundamental as freedom of speech or association, as they are direct expressions of individual freedom. Value Pluralism perspective: Critics argue that Rawls, in selecting which freedoms are “basic,” relies on a specific conception of citizenship and democratic society that not everyone shares. For example, cultures or individuals that value economic freedom more highly as a pillar of autonomy may view the exclusion of these freedoms as an arbitrary imposition of egalitarian values. Arbitrariness in the choice of freedoms: The critique maintains that Rawls’s criteria for defining basic freedoms—those necessary for the exercise of the two moral capacities (sense of justice and conception of the good)—are subjective or insufficiently justified. Why, for example, would freedom of conscience be more essential than the freedom to use property as one wishes? |

The second principle regulates social and economic inequalities and consists of two parts: the fair equality of opportunity clause and the difference principle. The fair equality of opportunity clause states that everyone should have a fair and equal opportunity to compete for desirable offices and positions, whether public or private. This implies that society must provide all citizens with the basic means necessary to participate in such competition, including appropriate education and health care.

The difference principle, in turn, requires that any unequal distribution of wealth and income be such that those who are worst off are better than they would be under any other distribution consistent with the first principle, including an equal distribution. Rawls maintains that some inequality of wealth and income is likely necessary to maintain high levels of productivity, but only if this inequality also benefits the least advantaged.

According to Rawls, fair equality of opportunity is achieved in a society when all people with the same native talent (genetic endowment) and the same degree of ambition have the same prospects of success in all competitions for positions that confer special economic and social advantages. This is a very demanding understanding of meritocracy, which goes beyond the simple abolition of legal barriers to competition.

Rawls establishes a lexical priority between the principles, meaning that the first principle (liberty) has absolute priority over the second principle (equality). The basic liberties cannot be infringed under any circumstances, even if doing so would increase aggregate welfare, improve economic efficiency, or raise the incomes of the poor. This lexical priority ensures that considerations of utility or efficiency can never be used to justify violations of basic rights.

| What Experiments Have to Say About Theories of Justice Norman Frohlich and Joe A. Oppenheimer, often collaborating with Cheryl L. Eavey, offered a significant empirical critique of John Rawls’s theory of justice, particularly its core assumptions about decision-making in the “original position” behind the “veil of ignorance.” Their work, detailed in publications like their 1987 article in the American Journal of Political Science and their 1992 book Choosing Justice: An Experimental Approach to Ethical Theory, used laboratory experiments to test whether real people, placed in conditions simulating Rawls’s hypothetical scenario, would actually select his proposed principles of justice. To empirically evaluate Rawls’s theory, Frohlich and Oppenheimer designed experiments that mimicked the original position’s impartiality through “imperfect information.” Participants (typically university students) were divided into small groups (e.g., 4–5 people) and tasked with unanimously agreeing on a principle for distributing income in a hypothetical society. They were informed that their actual earnings from the experiment would be determined by the chosen principle, but they wouldn’t know their individual productivity or position in the income distribution until after the decision—enforcing a veil of ignorance. Participants ranked and discussed four possible distributive principles: – Maximizing the floor income (Rawls’s difference principle, or maximin: ensuring the worst-off get the highest possible minimum). – Maximizing the average income (utilitarian: focusing on overall societal wealth without regard for distribution). – Maximizing the average with a floor constraint (a minimum safety net, above which inequalities are allowed to maximize averages). – Maximizing the average with a range constraint (limiting the gap between the richest and poorest). Discussions were structured to encourage consensus, and variations included higher-stakes payoffs, scenarios with potential losses, and different group sizes to test robustness. Across multiple experiments (e.g., 44 groups in one study), the results consistently contradicted Rawls’s predictions: – High Consensus Achievement: Groups almost always reached unanimous agreement (100% in some designs), supporting Rawls’s idea that impartial reasoning can lead to consensus. – Rejection of the Difference Principle: No group ever selected Rawls’s maximin principle. It was the least popular, receiving the fewest first-place rankings (only 9 out of hundreds) and the most last-place rankings (106). Participants viewed it as overly restrictive and inefficient. – Preference for an “Intuitionistic” Principle: The overwhelming majority (79% of groups, or 35 of 44 in one experiment) of participants chose to maximize average income with a minimum floor income to provide a safety net. This extremely important experiment suggests that while theoretical philosophical discussions about justice can be interesting, real people may not agree with what “enlightened” elites think about what justice is. |

Political Liberalism and Later Developments

In “Political Liberalism” (1993), Rawls further developed his theory to address how a government can be just when citizens have many different ideas about religion, morality, and what constitutes a good life. He argued that these disagreements are normal in a free society, and the challenge is how a government can be just and legitimate despite these differences.

Rawls introduced the concept of “public reason,” arguing that a just government must use reasons that everyone can understand and accept when discussing public issues. For example, a judge deciding a case should not use their personal religious beliefs but rather use reasons shared by all, like the idea of protecting children. This “duty of civility” applies to both government leaders and citizens deciding whom to vote for.

Rawls also slightly updated his principles of justice in this later work. The first principle came to establish that every person has an equal right to a complete set of basic rights and liberties, which must be the same for all, with political liberties needing to be truly valuable for all. The second principle maintained its dual structure, but with renewed emphasis on the need for social and economic differences to particularly benefit the least fortunate members of society.

The development of political liberalism represented Rawls’ response to criticisms that his original theory was overly metaphysical or reliant on a particular conception of human good. By reformulating his theory as “political, not metaphysical,” Rawls sought to demonstrate that the principles of justice could be endorsed by people with different comprehensive views of life, as long as they shared a commitment to basic democratic ideals.

This move toward political liberalism also reflected Rawls’ recognition that modern democratic societies are characterized by what he called the “fact of reasonable pluralism”—the reality that free and equal citizens will inevitably develop different religious, philosophical, and moral comprehensive doctrines. A suitable theory of justice for such societies must be able to achieve an “overlapping consensus” among these different doctrines.

| Criticisms of Rawls’s “Political Liberalism” Although influential in certain circles, the book faced significant criticism from various philosophical perspectives. Below are some of them: 1. Overlapping Consensus: Unrealistic or Unstable Rawls’s idea of an overlapping consensus—where diverse groups support a shared political conception of justice for different reasons—is criticized as either unrealistic or unstable: – Feasibility: Critics argue that achieving consensus in deeply pluralistic societies is unlikely, as comprehensive doctrines (e.g., religious or ideological beliefs) often conflict irreconcilably on fundamental issues like abortion or economic redistribution. – Stability Concerns: Even if achieved, the consensus may be fragile. Tha overlapping consensus relies on citizens prioritizing public reason, but strong ideological commitments (e.g., fundamentalism) could undermine this, leading to instability. – Exclusion of Non-Liberal Views: The consensus assumes “reasonable” doctrines, but defining reasonableness is contentious. Critics argue Rawls implicitly biases the framework toward liberal values, marginalizing non-liberal or illiberal perspectives (e.g., communitarian or authoritarian views), which undermines pluralism. 2. Public Reason: Restrictive and Ambiguous Rawls’s concept of public reason—where political decisions must be justified using reasons all citizens can accept—faces criticism for being overly restrictive and vague: – Restricts Free Expression: Some critics argue that public reason limits citizens’ ability to draw on their comprehensive doctrines in public debate, stifling authentic moral or religious arguments (e.g., on issues like same-sex marriage). This could alienate religious citizens or those with non-liberal views, as their deepest convictions are sidelined. – Ambiguity in Application: Some critics point out that public reason’s boundaries are unclear. For instance, how do you distinguish “public” from “comprehensive” reasons in complex debates (e.g., bioethics)? This ambiguity risks inconsistent or arbitrary application. – Bias Toward Liberalism: Public reason implicitly favors secular, rationalist arguments, which critics argue privileges liberal elites and marginalizes marginalized groups whose reasoning may be rooted in non-liberal frameworks. 3. Philosophical Foundations: Neutrality vs. Justification Rawls aims for a “freestanding” political conception of justice, neutral among comprehensive doctrines, but critics question its coherence: – Neutrality Is Impossible: Critics argue that no political theory can be truly neutral, as Rawls’s framework implicitly endorses liberal values (e.g., autonomy, equality) over others, making it a disguised comprehensive doctrine. – Weak Normative Force: Communitarians argue that by avoiding metaphysical commitments, Rawls’s theory lacks the moral depth to justify why citizens should prioritize justice over their personal beliefs, weakening its prescriptive power. – Circular Reasoning: Some suggest Rawls’s reliance on reasonable pluralism to justify the political conception creates a circular argument, as “reasonableness” is defined by liberal assumptions. 4. Limited Scope and Practicality – Narrow Focus on Constitutional Essentials: Rawls limits his theory to “constitutional essentials” and basic justice, but critics argue this sidesteps pressing everyday issues like cultural conflicts or economic policy details, limiting its practical utility. – Empirical Disconnect: Experimental critiques, like those from Frohlich and Oppenheimer (discussed previously), suggest Rawls’s assumptions about rational agreement don’t hold up empirically, even in pluralistic settings, as people prioritize mixed principles over strict egalitarianism. 5. Communitarian and Cultural Critiques Communitarians argue that Rawls’s focus on individual autonomy and abstract principles neglects community, tradition, and cultural identity: – Atomistic Individuals: Some criticize Rawls for assuming individuals can reason as detached agents, ignoring how identities are shaped by communal values, which are essential for social cohesion. – Cultural Relativism: Some argue that Rawls’s universalist liberal framework doesn’t account for cultural differences in conceptions of justice, potentially imposing Western values on non-liberal societies. Conclusion While Rawls aimed to create a framework for stability in pluralistic societies, critics argue it’s either too restrictive, too liberal-centric, or insufficiently attentive to real-world power dynamics and cultural diversity. |

Classification in the Circular Diagram of Political Mentalities

Rawls’s position can be understood as a synthesis of different traditions. On the one hand, his emphasis on individual rights and the priority of liberty (excluding basic rights such as freedom of contract and the right to ownership of the means of production) brings him only partially closer to the classical liberal tradition. On the other hand, his strong commitment to distributive justice and fair equality of opportunity places him firmly within the modern social-liberal tradition. This borderline position is consistent with his role as a central figure in what could be characterized as part of the moderate left, bordering on classical liberalism.

| Two counterexamples Robert Nozick (1938–2002) was an American philosopher. In his book “Anarchy, State, and Utopia,” he gives a counterexample to explain why, in his opinion, Rawls’s theory is morally wrong: “The principle of fairness, as we stated it following Hart and Rawls, is objectionable and unaccept able. Suppose some of the people in your neighborhood (there are 364 other adults) have found a public address system and decide to institute a system of public entertainment. They post a list of names, one for each day, yours among them. On his assigned day (one can easily switch days) a person is to run the public address system, play records over it, give news bulletins, tell amusing stories he has heard, and so on. After 138 days on which each person has done his part, your day arrives. Are you obligated to take your turn? You have benefited from it, occasionally opening your window to listen, enjoying some music or chuckling at someone’s funny story. The other people have put themselves out. But must you answer the call when it is your turn to do so? As it stands, surely not. Though you benefit from the arrangement, you may know all along that 364 days of entertainment supplied by others will not be worth your giving up one day. You would rather not have any of it and not give up a day than have it all and spend one of your days at it. Given these preferences, how can it be that you are required to participate when your scheduled time comes? It would be nice to have philosophy readings on the radio to which one could tune in at any time, perhaps late at night when tired. But it may not be nice enough for you to want to give up one whole day of your own as a reader on the program. Whatever you want, can others create an obligation for you to do so by going ahead and starting the program themselves? In this case you can choose to forgo the benefit by not turning on the radio; in other cases the benefits may be unavoidable. If each day a different person on your street sweeps the entire street, must you do so when your time comes? Even if you don’t care that much about a clean street? Must you imagine dirt as you traverse the street, so as not to benefit as a free rider? Must you refrain from turning on the radio to hear the philosophy readings? Must you mow your front lawn as often as your neighbors mow theirs?” It’s possible to imagine worse scenarios. Imagine the government decides there are social disadvantages because some people don’t have access to certain cultural goods. Classical music, for example. They conducted a study that found a strong correlation between access to classical music and employability. Based on this data, the government concluded that employers are biased against people who lack adequate knowledge of these cultural goods. So, they decide to install a sound system in front of your house (and in many other places) that plays Bach, Mozart, and Beethoven all day long. If you belong to the category of those the government considers privileged, you will be taxed and still have the “pleasure” of receiving the good the government is offering you. If you belong to the category of those who are disadvantaged, you will have the pleasure of receiving the good the government is offering you “for free.” Finally, suppose you don’t like classical music, but prefer rock. |

Conclusion

John Rawls and his theory of justice as fairness represent an important contribution to modern political philosophy, offering a sophisticated conceptual framework for thinking about justice, equality, and political legitimacy in a democratic society. Despite the limitations of his assumptions and the fact that empirical results demonstrate the fallacy of his model of justice, his framework has become popular in academic circles (especially among intellectuals, usually lef-wing), allowing them to assert their own beliefs (as Rawls himself did) while proclaiming them as universal truths.

Questions for reflection

1. If a theory of justice as fairness is a theory with claims of rationality, if the facts contradict it (Norman Frohlich, Joe A. Oppenheimer, and Cheryl L. Eavey), shouldn’t the consequence be its rejection? What justifies its continued popularity?

2. Given the criticisms of Rawls’s theory as being too abstract, how could empirical experiments like those mentioned challenge or refine its premises about human rationality?

3. Reflect on the empirical experiments of Norman Frohlich, Joe A. Oppenheimer, and Cheryl L. Eavey that rejected the difference principle—could similar studies influence policies on income floors in welfare reforms today?

4. How can the concept of the veil of ignorance be applied in the real world, with real people, with broad cultural diversity?

5. Consider libertarian criticisms, such as those of Robert Nozick, of Rawls’s exclusion of certain economic liberties from basic freedoms—do they have relevance to current discussions about health care?

6. How do libertarian critics, such as Robert Nozick, challenge Rawls’s difference principle, arguing that it undermines individual liberty and property rights?

7. How do critics address the abstraction and idealization present in Rawls’s original position and the veil of ignorance, arguing that they ignore the complexities and power dynamics of the real world?

8. To what extent is Rawls’s focus on distributive justice criticized for neglecting other forms of justice, such as recognition justice and restorative justice?

9. How do communitarian critics argue that Rawls’s emphasis on individualism fails to account for the role of communal and cultural values in constructing justice?

10. To what extent is Rawls’s concept of public reason criticized for potentially excluding certain moral or religious views from public discourse?

11. Corporate strategy is usually structured around mission, vision, values, and macroprocesses. The mission describes what the company is doing (what it is). The vision describes where it wants to go (its goals, what it wants to be, where it wants to go). Values define the limits of the company’s action. That is, even if the company desires to reach a certain position, it is not willing to do certain things to get there. Macroprocesses are a first breakdown of what will be done to get there. Vision and processes are utilitarian calculations. Considering this example, is there a need to construct an abstract framework, like Rawls’s, to limit the utilitarian tendency of human action, or should the focus be on greater clarity regarding societal values (in the case of corporations, the values of the corporation. In the case of human beings, in Western societiesy, the values of the Judeo-Christian tradition)?

Leave a comment