Introduction

Eduard Bernstein (1850 – 1932) was a German social democratic politician. A member of the Social Democratic Party (SPD), developed these ideas in the late 19th century amid a period of relative economic stability in Europe, particularly during his exile in Switzerland and London (1878–1901) under Germany’s Anti-Socialist Laws, which banned socialist activities.

Figure 23. Eduard Bernstein

Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Eduard_Bernstein.jpg

Influenced by Friedrich Engels (with whom he collaborated closely until Engels’s death in 1895) and the reformist British Fabian Society, Bernstein observed that Victorian-era capitalism was not leading to the crises Marx foresaw. His seminal work, The Preconditions of Socialism (1899), sparked the “Revisionist Debate” within the German Social Democratic Party (SPD), pitting him against orthodox Marxists like Karl Kautsky and Rosa Luxemburg, who accused him of betraying revolutionary principles. Despite criticism, the SPD’s practical policies often leaned reformist, especially after the laws were lifted in 1890. Bernstein returned to Germany in 1901, served in the Reichstag, and supported the Weimar Republic, reflecting a broader shift in socialism toward parliamentary democracy in the early 20th century.

Main ideas

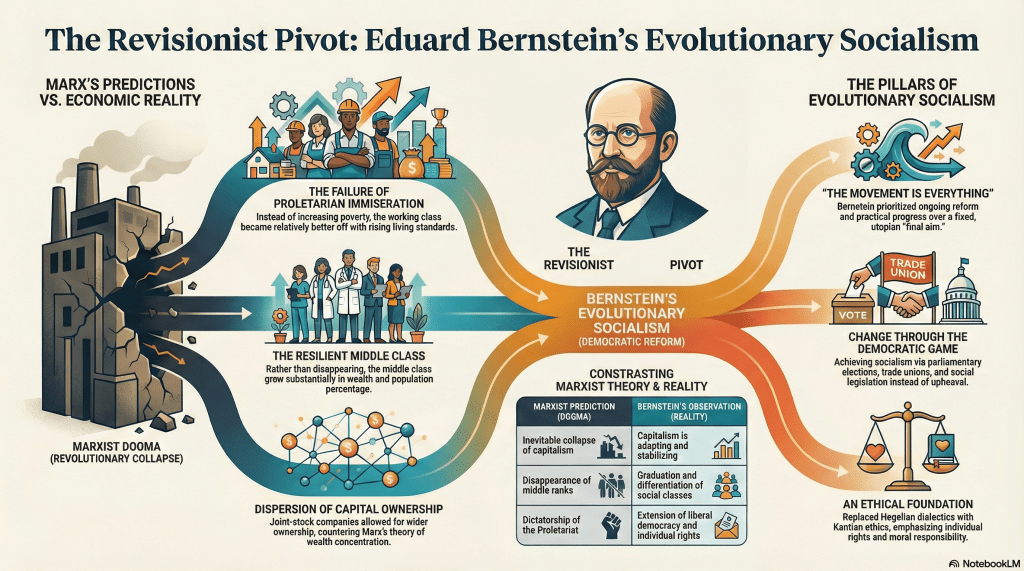

Bernstein is best known for his evolutionary socialism, often called revisionism, in which he proposed a gradual, reformist path to socialism rather than the revolutionary upheaval advocated by orthodox Marxism. Key ideas include:

- Rejection of Marxist Determinism: Bernstein challenged Karl Marx’s predictions, arguing that capitalism was not inevitably collapsing due to internal contradictions. Instead, he observed that capitalism was adapting and stabilizing, with phenomena like the growth of joint-stock companies dispersing ownership, the persistence of small and medium-sized enterprises, and rising living standards for the working class, countering Marx’s theory of proletarian immiseration (increasing poverty).

- Gradual Reforms Over Revolution: Socialism could be achieved through peaceful, incremental changes within democratic systems, such as parliamentary elections, trade unions, cooperatives, and social legislation. He famously prioritized the “movement” (ongoing reform efforts) over any fixed “final aim” of socialism, emphasizing practical progress.

- Ethical and Democratic Focus: Drawing from Kantian philosophy rather than Hegelian dialectics, Bernstein stressed ethics, individual rights, and democracy. He opposed the “dictatorship of the proletariat” as undemocratic and advocated for socialism as an extension of liberal democracy, not its overthrow.

In essence, Bernstein viewed socialism as an evolutionary process embedded in capitalist society, achievable through education, organization, and political participation rather than class warfare.

| Marx’s three failed predictions Stephen Ronald Craig Hicks (1960) is a Canadian-American philosopher. In his 2024 article “Marx’s three failed predictions,” Hicks wrote: “Yet that was not how it worked out. By the early twentieth century it seemed that all three of the predictions failed to characterize the development of the capitalist countries. The class of manual laborers had both declined as a percentage of the population and become relatively better off. And the middle class had grown substantially both as a percentage of the population and in wealth, as had the upper class.” (https://www.stephenhicks.org/2024/01/19/marxs-three-failed-predictions-ep/) |

Classification in the Circular Diagram of Western Political Mentalities

Bernstein’s evolutionary socialism fits squarely within the Democratic Leftists group. This category aligns with his advocacy for redistribution, greater equality, and incremental changes via parliamentary democracy, rather than radical upheaval. It contrasts with Radical Leftists (who favor revolution) and shares some reformist edges with Classical Liberals (through democratic values), reflecting the diagram’s circular logic where Democratic Leftists connect back to liberals in emphasizing individual rights within a collective framework. Historically, this places Bernstein’s ideas in post-WWII social democracy, as seen in parties like Sweden’s Social Democrats.

Key Quotes

“I set myself against the notion that we have to expect shortly a collapse of the bourgeois economy, and that social democracy should be induced by the prospect of such an imminent, great, social catastrophe to adapt its tactics to that assumption. That I maintain most emphatically.”

“Social conditions have not developed to such an acute opposition of things and classes as is depicted in the Manifesto. It is not only useless, it is the greatest folly to attempt to conceal this from ourselves.”

“The theory of labour value is above all misleading in this that it always appears again and again as the measure of the actual exploitation of the worker by the capitalist, and among other things, the characterisation of the rate of surplus value as the rate of exploitation reduces us to this conclusion. It is evident from the foregoing that it is false as such a measure, even when one starts from society as a whole and places the total amount of workers’ wages against the total amount of other incomes.”

“It is thus quite wrong to assume that the present development of society shows a relative or indeed absolute diminution of the number of the members of the possessing classes. Their number increases both relatively and absolutely.” (…) “Far from society being simplified as to its divisions compared with earlier times, it has been graduated and differentiated both in respect of incomes and of business activities.”

“If the collapse of modern society depends on the disappearance of the middle ranks between the apex and the base of the social pyramid, if it is dependent upon the absorption of these middle classes by the extremes above and below them, then its realisation is no nearer in England, France, and Germany to-day than at any earlier time in the nineteenth century.”

“The return to the Communist Manifesto points here to a real residue of Utopianism in the Marxist system.” (…) “Nothing confirms me more in this conception than the anxiety with which some persons seek to maintain certain statements in Capital, which are falsified by facts.”

Relevance Today

Bernstein’s evolutionary socialism remains highly relevant in contemporary politics, both as a critique revealing the falsity of Marx’s propositions and as a cornerstone of modern social democracy and democratic socialism worldwide. His emphasis on gradual reforms resonates with policies that combat inequality through democratic means. Furthermore, Bernstein’s ideas seek a balance between neoliberal austerity and far-left radicalism, seeking a pragmatic socialism with some ethical limits that seeks to adapt to the evolution of free market.

| Labour’s Clause IV The British Labour Party’s Clause IV (from its Rule Book) represents one of the most iconic socialist commitments in 20th-century European politics. Adopted by the Labour Party in 1918, it declared the aim to “secure for the workers by hand or by brain the full fruits of their industry and the most equitable distribution thereof that may be possible upon the basis of the common ownership of the means of production, distribution and exchange, and the best obtainable system of popular administration and control of each industry or service”. While the 1918 text appeared radical with its call for common ownership, it reflected a compromise influenced by Fabian gradualism, which echoed Bernstein’s reformism. However, the ultimate influence of Bernstein’s ideas was clearly manifested in Tony Blair’s amendment of Clause IV in 1995, with his “New Labourism”: “Clause IV. Aims and values The Labour Party is a democratic socialist Party. It believes that by the strength of our common endeavour we achieve more than we achieve alone, so as to create for each of us the means to realise our true potential and for all of us a community in which power, wealth and opportunity are in the hands of the many not the few; where the rights we enjoy reflect the duties we owe and where we live together freely, in a spirit of solidarity, tolerance and respect. To these ends we work for: A. A DYNAMIC ECONOMY, serving the public interest, in which the enterprise of the market and the rigour of competition are joined with the forces of partnership and co-operation to produce the wealth the nation needs and the opportunity for all to work and prosper with a thriving private sector and high-quality public services where those undertakings essential to the common good are either owned by the public or accountable to them. (…)” The transformation incorporated many of the principles Bernstein had championed decades earlier: the rejection of violent revolution, the acceptance of the capitalist system as reformable, and the belief that social progress could be achieved through gradual reforms within existing democratic structures, reflecting Bernstein’s vision of a market-driven mixed economy with a central role for capitalism and entrepreneurship. |

Questions for Reflection

1. By the end of the 19th century, Marxists, like Bernstein, already knew that Marx was wrong in all his relevant propositions. The path Bernstein proposed was to play the democratic game. What other paths do you imagine Marxists followed?

2. Imagine two paths. One that has proven wrong, which requires violence and the murder of many people, and which, in the end, causes more harm to those it purports to benefit than doing nothing (given that people are improving their conditions within the established game). The other requires intelligence, adaptation, and the ability to engage in dialogue (with the prospect of improving the outcome of the game). Which would you choose?

3. How does Bernstein’s rejection of Marx’s prediction of capitalism’s inevitable collapse due to internal contradictions reflect on the resilience of modern capitalist economies, and what lessons can this offer for contemporary debates on economic inequality in countries like the United States?

4. In what ways does Bernstein’s observation of growing middle classes and improved living standards for workers challenge orthodox Marxist views?

5. What relevance does Bernstein’s observation about improving social conditions and universal suffrage under capitalism have for contemporary movements of “democratic socialism”?

6. Considering Bernstein’s prioritization of the “movement” over a fixed “final aim” in socialism, how does this perspective critique utopian ideologies in current political discourse, particularly in debates over achievable climate goals or universal basic income?

7. Reflect on Bernstein’s support for parliamentary democracy and rejection of the dictatorship of the proletariat—how could this underscore the risks of authoritarian tendencies in leftist regimes, as seen in critiques of governments in Venezuela or Cuba?

8. How does Bernstein’s integration of ethical dimensions into Marxism—following Kant in treating human beings as ends in themselves—inform debates about humanistic values versus economic determinism in contemporary socialism?

Leave a comment