Carl Schmitt (1888–1985), a German jurist and political theorist, is renowned for his conservative and realist critiques of modern politics, liberalism, and democracy. His work, influenced by his Catholic background and experiences during the Weimar Republic and Nazi era, emphasizes conflict, decision-making, and authority as central to politics. His key works are The Concept of the Political (1932) and Political Theology (1922).

Figure: Carl Schmitt

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Carl_Schmitt.jpg

| Association with Authoritarianism and Nazism The main controversy surrounding Schmitt stems from his direct ties to the Nazi regime and the authoritarian implications of his work. After joining the Nazi Party on May 1, 1933, he quickly became one of the Third Reich’s leading legal theorists. This affiliation was more than opportunistic; it signaled an active endorsement of totalitarian practices. Critics argue that the problem is not only historical association but that Schmitt’s theories supply intellectual justification for totalitarianism. They claim his ideas were not merely appropriated by the Nazis but were articulated in ways that legitimize authoritarian power structures. |

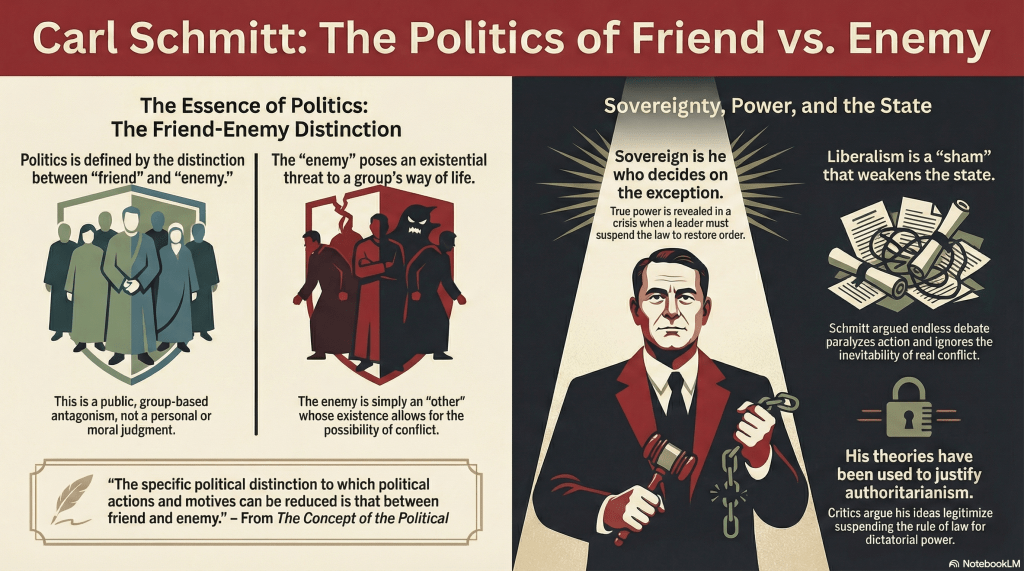

The Friend-Enemy Distinction as the Core of Politics

Schmitt argues that politics arises from the fundamental human tendency to form groups based on collective identities, leading to inevitable conflict. For him, politics is fundamentally defined by the existential distinction between “friend” and “enemy,” where the enemy represents an “other” whose existence poses a threat to one’s way of life, potentially leading to mortal conflict. This is not about personal hatred or moral judgments but a public, group-based antagonism that arises from differences in identity, culture, or beliefs—such as “embodiments of ‘different and alien’ ways of life.” For Schmitt, this distinction is the “utmost degree of intensity … of an association or dissociation,” and it constitutes political communities by uniting “friends” against outsiders. He viewed conflict as an ineradicable aspect of human nature, rooted in anthropological pessimism and concepts like Original Sin, rejecting utopian ideals that seek to eliminate antagonism.

Sovereignty and the State of Exception

A famous dictum from Schmitt is: “Sovereign is he who decides on the exception.” Sovereignty, for him, is not bound by legal norms but revealed in crises or emergencies (the “state of exception”), where the sovereign must suspend the law to restore order using extra-legal means. This “decisionism” underscores that politics requires decisive authority beyond rules, as norms presuppose a stable “homogeneous medium” that collapses in chaos. In practice, this justified expansive presidential powers during Weimar crises, prioritizing “democratic legitimacy” over constitutional limits.

| Criticisms of the State of Exception and Sovereignty Schmitt’s concept of sovereignty as “the one who decides on the exception” faces significant objections due to its implications for the rule of law and democratic governance. Critics argue that unlimited personal power represents a potencial excuse for dictatorial power. The sovereign ability to suspend the law during emergencies is seen as potentially dangerous, as emergency dictatorships rarely remain “temporary.” Furthermore, once the exception is normalized, the impediments to naming opponents as enemies and using the state machinery to persecute them fall away, ultimately producing a continued erosion of constitutional protections under the guise of crisis management, ultimately destroying the rule of law. |

Critique of Liberalism and Parliamentary Democracy

Schmitt was a sharp critic of liberalism, seeing it as an attempt to depoliticize society by reducing conflicts to neutral discussions, economics, or moral debates, which he believed ignores the inevitability of enmity. Liberalism, in his view, treats enemies as mere competitors, leading to “de-politicization” and weakening the state’s ability to protect itself. He attacked parliamentary democracy as a “sham,” incapable of reconciling pluralism with the need for political unity, arguing that endless debate paralyzes action in the face of real threats. True democracy, for Schmitt, requires a homogeneous people capable of decisive collective will, not liberal individualism.

Political Theology

Schmitt claimed that “all key concepts of the modern doctrine of the state are secularized theological concepts,” linking politics to theology. The sovereign’s decision on the exception mirrors God’s miraculous intervention, and authority needs “transcendental, extrarational, and supramaterial sources” to ground it. He viewed humans as “by nature evil and licentious,” requiring a strong state to curb chaos, with liberalism’s rejection of this as hubris against divine order.

| Schmitt vs. Catholic Political Thought Carl Schmitt’s political theories and Catholic Church teachings represent fundamentally opposed approaches to politics, authority, and human society. While Schmitt developed a theory based on the friend-enemy distinction and unlimited sovereign decision that culminated in his support for Nazism, the Catholic Church grounds its political vision in natural law, human dignity, and the common good. Schmitt’s decisionism places sovereign power above all moral constraints, whereas Catholic social doctrine insists that all legitimate authority must serve human dignity and operate within objective moral limits. Their concepts of sovereignty differ dramatically. Schmitt’s famous definition of the sovereign as “he who decides on the exception” justifies unlimited executive power and the suspension of legal order during crises. In contrast, Catholic political theory emphasizes subsidiarity and the limitation of authority, where even papal power operates within doctrinal and canonical frameworks. The Catholic tradition maintains that unjust authority loses its legitimacy, directly opposing Schmitt’s theory of sovereign exception. Regarding political conflict, Schmitt views antagonism as the essence of politics, defining the political through existential friend-enemy distinctions. Catholic social doctrine emphasizes solidarity and the principle that “we are friends and brothers of every human being”, seeking to transform conflict into collaboration rather than institutionalizing enmity. While Schmitt rejects liberal pluralism as fragmenting political will, the Catholic Church has endorsed religious freedom and democratic governance while maintaining moral principles. The historical consequences of these opposing visions prove decisive. Schmitt’s theories provided intellectual justification for Nazi totalitarianism, as he endorsed Hitler’s assassinations of political opponents and anti-Jewish policies. Catholic social doctrine has consistently opposed totalitarianism in all forms, with figures like John Paul II playing key roles in resisting both communist and fascist regimes. |

Key Quotes

“Sovereign is he who decides on the exception.” (From Political Theology)

“All significant concepts of the modem theory of the state are secularized theological concepts not only because of their historical development-in which they were transferred from theology to the theory of the state, whereby, for example, the omnipotent God became the omnipotent lawgiver-but also because of their systematic structure, the recognition of which is necessary for a sociological consideration of these concepts. The exception in jurisprudence is analogous to the miracle in theology. Only by being aware of this analogy can we appreciate the manner in which the philosophical ideas of the state developed in the last centuries.” (From Political Theology).

“The essence of liberalism is negotiation, a cautious half measure, in the hope that the definitive dispute, the decisive bloody battle, can be transformed into a parliamentary debate and permit the decision to be suspended forever in an everlasting discussion.” (From Political Theology).

“The specific political distinction to which political actions and motives can be reduced is that between friend and enemy.(…) The distinction of friend and enemy denotes the utmost degree of intensity of a union or separation, of an association or dissociation. It can exist theoretically and practically, without having simultaneously to draw upon all those moral, aesthetic, economic, or other distinctions. The political enemy need not be morally evil or aesthetically ugly; he need not appear as an economic competitor, and it may even be advantageous to engage with him in business transactions. But he is, nevertheless, the other, the stranger; and it is sufficient for his nature that he is, in a specially intense way, existentially something different and alien, so that in the extreme case conflicts with him are possible. These can neither be decided by a previously determined general norm nor by the judgment of a disinterested and therefore neutral third party. (From The Concept of the Political).

“The concept of humanity is an especially useful ideological instrument of imperialist expansion, and in its ethical-humanitarian form it is a specific vehicle of economic imperialism. Here one is reminded of a somewhat modified expression of Proudhon’s: whoever invokes humanity wants to cheat. To confiscate the word humanity, to invoke and monopolize such a term probably has certain incalculable effects, such as denying the enemy the quality of being human and declaring him to be an outlaw of humanity; and a war can thereby be driven to the most extreme inhumanity.” ” (From The Concept of the Political).

“The political entity presupposes the real existence of an enemy and therefore coexistence with another political entity. As long as a state exists, there will thus always be in the world more than just one state. A world state which embraces the entire globe and all of humanity cannot exist.” (From The Concept of the Political ).

Schmitt in the Circular Diagram of Western Political Mentalities

Carl Schmitt best fits within the Authoritarian Conservatives group in the Circular Diagram of Western Political Mentalities. This classification aligns with his emphasis on strong state authority, hierarchy, traditionalism, and a view of the world as inherently conflictual and requiring decisive order—characteristics that define this mentality.

| Carl Schmitt’s ideas compared with Russell Kirk’s traditionalist conservatism. Carl Schmitt’s ideas share some foundational alignments with Russell Kirk’s canons of conservatism, particularly in their mutual emphasis on hierarchy, tradition, and a rejection of liberal egalitarianism and abstract rationalism. Both thinkers value an organic, historically rooted social order over utopian reconstructions, and Schmitt’s political theology echoes Kirk’s belief in a transcendent moral framework. However, Schmitt diverges significantly in his decisionism and embrace of radical action during states of exception, which Kirk would likely view as imprudent innovation risking societal conflagration. Schmitt’s association with the Nazi regime further distances him from Kirk’s prudent, Burkean conservatism, making their proximity moderate at best—close in anti-liberal critique but far in methodological extremism and ethical implications. | |||

| Kirk’s Canon | Description | Schmitt’s Related Idea | Agreement/ Disagreement |

| 1. Belief in a transcendent order or natural law | Conservatives believe in an enduring moral order governed by divine providence or natural law that rules society and conscience. | Schmitt’s political theology posits that modern political concepts are secularized theological ones, and he viewed sovereignty as mirroring divine authority. As a Catholic, he believed in the inherent evil of man and the need for order beyond human constructs. | Agreement: Both emphasize a higher moral or theological foundation for politics, rejecting pure secular rationalism. |

| 2. Affection for the variety and mystery of human existence | Conservatives value custom, convention, continuity, and the diversity of human traditions over uniformity and egalitarianism. | Schmitt critiqued liberalism for depoliticizing society and imposing universal norms, favoring concrete, historical “orders” and distinctions (e.g., friend-enemy) that preserve existential variety. | Agreement: Schmitt opposed the homogenizing tendencies of liberalism, aligning with Kirk’s appreciation for organic diversity. |

| 3. Conviction that civilized society requires orders and classes | Society needs hierarchy and classes for stability, opposing classless egalitarianism. | Schmitt supported authoritarian structures and hierarchy, viewing liberal equality as illusory and advocating for strong leadership to maintain order. | Agreement: Both endorse social stratification and reject radical egalitarianism. |

| 4. Persuasion that freedom and property are closely linked | Freedom is tied to private property, and economic leveling harms progress. | Schmitt was skeptical of liberal economic freedoms, seeing them as part of depoliticization, but he did not explicitly oppose property; his focus was on state sovereignty over individual rights. | Partial Disagreement: Schmitt prioritized state decisionism over individual freedoms and property rights, viewing them as secondary to political unity. |

| 5. Faith in prescription and distrust of abstract designs | Trust in inherited traditions and skepticism toward rationalist reconstructions of society. | Schmitt’s decisionism emphasized concrete situations over abstract norms, distrusting parliamentary liberalism’s proceduralism as avoiding real decisions. | Agreement: Both distrust abstract, utopian schemes, favoring historically grounded authority. |

| 6. Recognition that change is not always salutary | Prudent reform over hasty innovation, which can lead to destruction rather than progress. | Schmitt advocated for decisive action in states of exception, supporting radical shifts like the Nazi regime to restore order, viewing liberalism’s incrementalism as weakness. | Disagreement: Schmitt’s embrace of emergency powers and revolutionary decisions contrasts with Kirk’s caution against rapid change. |

Schmitt’s ideas, such as the sovereign’s power to decide on the “state of exception” and the friend-enemy distinction as the essence of politics, reflect a preference for centralized control and stability over liberal pluralism or democratic deliberation, positioning him adjacent to Moderate Conservatives (sharing traditional values) and Radical Statists (sharing authoritarian tendencies like militarism and strong government).

| Carl Schmitt’s ideas compared with Mussolini and Rocco’s fascism In relation to fascism as articulated by Mussolini and Rocco, Schmitt’s thought is notably closer, providing intellectual underpinnings that resonated with fascist regimes. His anti-liberalism, statism, and friend-enemy dichotomy align closely with fascism’s total state, nationalism, and acceptance of violence. While Schmitt was not a core fascist ideologue and focused more on legal theory than economic corporatism, his ideas on sovereignty and the political complemented Mussolini’s absolutist state and Rocco’s authoritarian hierarchy. The distance is minimal; Schmitt’s work can be seen as a philosophical bridge to fascism, though he maintained some conservative reservations that prevented full ideological merger. | |||

| Fascist Thinker | Key Idea | Schmitt’s Related Idea | Agreement/ Disagreement |

| Benito Mussolini | Anti-individualism and statism: The state is absolute, individuals subordinate; opposes liberalism, democracy, and socialism. | Schmitt’s concept of sovereignty emphasizes the state’s decision-making power over norms, critiquing liberalism for weakening the political. | Agreement: Both prioritize the state over individual rights and reject liberal parliamentarism. |

| Benito Mussolini | Nationalism and imperialism: Fascism seeks national greatness through expansion and unity. | Schmitt’s friend-enemy distinction defines politics as existential conflict, often along national lines, supporting strong unified polities. | Agreement: Schmitt’s ideas justify nationalistic confrontations and unity against enemies. |

| Benito Mussolini | Corporatism: Economic organization under state control, integrating labor and capital. | Schmitt favored a strong state overriding economic liberalism but did not emphasize corporatism; his focus was legal-political rather than economic. | Partial Agreement: Both see the state directing society, but Schmitt was less focused on economic models. |

| Benito Mussolini | Violence and action: Fascism embraces violence as a means to achieve goals, anti-pacifist. | Schmitt viewed politics as potentially violent friend-enemy antagonism, where the state decides on war. | Agreement: Both accept violence as inherent to the political realm. |

| Alfredo Rocco | Critique of liberalism and democracy: Sees them as leading to anarchy; advocates authoritarian state as ethical entity. | Schmitt’s anti-liberalism portrays democracy as homogenizing and ineffective, favoring decisive authority. | Agreement: Strong alignment in rejecting liberalism and promoting authoritarian solutions. |

| Alfredo Rocco | State supremacy: The state is superior to individuals, organizing society hierarchically. | Schmitt’s sovereignty as the decision on exception places the state (or sovereign) above all. | Agreement: Both elevate the state as the ultimate authority. |

| Alfredo Rocco | Syndicalism under fascism: Controlled unions and corporations to prevent class conflict. | Schmitt was influenced by syndicalist ideas early on but shifted to state-centric views; he supported Nazi total state. | Partial Agreement: Schmitt endorsed state control over society, similar to fascist syndicalism. |

| Alfredo Rocco | Cultural imperialism: Fascism imposes values and order aggressively. | Schmitt’s ideas on political theology and order imply imposing unity, but more theoretically. | Agreement: Both support imposing order, though Schmitt is less culturally prescriptive. |

In the diagram’s circular arrangement, Authoritarian Conservatives oppose Democratic Leftists, who prioritize democracy and equality— a dynamic evident in Schmitt’s critiques of parliamentary systems and universalist ideals, which he saw as weakening hierarchical order.

Historical support for this placement includes Schmitt’s brief association with authoritarian regimes in 1930s Germany, akin to examples like Franco’s Spain, where conservative traditionalism merged with statist control. However, he could possibly also be classified as a fascist or a proto-fascist with conservative elements, revealing, once again, how fluid political classifications and mentalities are.

Selected text

Carl Schmitt. Political Theology. Four Chapters on the Concept of Sovereignty. Translated by George Schwab. The University of Chicago Press: Chicago and London.

1. Definition of Sovereignty

Sovereign is he who decides on the exception.

Only this definition can do justice to a borderline concept. Contrary to the imprecise terminology that is found in popular literature, a borderline concept is not a vague concept, but one pertaining to the outermost sphere. This definition of sovereignty must therefore be associated with a borderline case and not with routine. It will soon become clear that the exception is to be understood to refer to a general concept in the theory of the state, and not merely to a construct applied to any emergency

decree or state of siege.

The assertion that the exception is truly appropriate for the juristic definition of sovereignty has a systematic, legal-logical foundation. The decision on the exception is a decision in the true sense of the word. Because a general norm, as represented by an ordinary legal prescription, can n~ver encompass a total exception, the decision that a real exception exists cannot there fore be entirely derived from this norm. “.: hen Robert von MohF said that the test of whether an emergency exists cannot be a juristic one, he assumed that a decision in the legal sense must be derived entirely from the content of a norm. But this is the question. In the general sense in which Mohl articulated his argument, his notion is only an expression of constitutional liberalism and fails to apprehend the independent meaning of the decision.

From a practical or a theoretical perspective, it really does not matter whether an abstract scheme advanced to define sover eignty (namely, that sovereignty is the highest power, not a derived power) is acceptable. About an abstract concept there will in general be no argument, least of all in the history of sovereignty. What is argued about is the concrete application, and that means who decides in a situation of conflict what constitutes the public interest or interest of the state, public safety and order, le salut public, and so on. The exception, which is not codified in the existing legal order, can at best be characterized as a case of extreme peril, a danger to the existence of the state, or the like. But it cannot be circumscribed factually and made to conform to a preformed law.

It is precisely the exception that makes relevant the subject of sovereignty, that is, the whole question of sovereignty. The precise details of an emergency cannot be anticipated, nor can one spell out what may take place in such a case, especially when it is truly a matter of an extreme emergency and of how it is to be eliminated. The precondition as well as the content of jurisdictional competence in such a case must necessarily be un limited. From the liberal constitutional point of view, there would be no jurisdictional competence at all. The most guidance the constitution can provide is to indicate who can act in such a case. If such action is not subject to controls, if it is not hampered in some way by checks and balances, as is the case in a liberal constitution, then it is clear who the sovereign is. He decides whether there is an extreme emergency as well as what must be done to eliminate it. Although he stands outside the normally

valid legal system, he nevertheless belongs to it, for it is he who must decide whether the constitution needs to be suspended in its entirety. All tendencies of modem constitutional development point toward eliminating the sovereign in this sense. The ideas of Hugo Krabbe and Hans Kelsen, which will be treated in the following chapter, are in line with this development. But whether the extreme exception can be banished from the world is not a juristic question. Whether one has confidence and hope that it can be eliminated depends on philosophical, especially on philosophical-historical or metaphysical, convictions.

There exist a number of historical presentations that deal with the development of the concept of sovereignty, but they are like textbook compilations of abstract formulas from which definitions of sovereignty can be extracted. Nobody seems to have taken the trouble to scrutinize the often-repeated but completely empty phraseology used to denote the highest power by the famous authors of the concept of sovereignty. That this concept relates to the critical case, the exception, was long ago recognized by Jean Bodin. He stands at the beginning of the modem theory of the state because of his work “Of the True Marks of Sovereignty” (chapter 10 of the first book of the Republic) rather than because of his often-cited definition (“sovereignty is the absolute and perpetual power of a republic”). He discussed his concept in the context of many practical examples, and he always returned to the question: To what extent is the sovereign bound to laws, and to what extent is he responsible to the estates? To this last, all-important question he replied that commitments are binding because they rest on natural law; but in emergencies the tie to general natural principles ceases. In general, according to him, the prince is duty bound toward the estates or the people only to the extent of fulfilling his promise in the interest of the people; he is not so bound under conditions of urgent necessity. These are by no means new theses. The decisive point about Bodin’s concept is that by referring to the emergency, he reduced his analysis of the relationships between prince and estates to a simple either/or.

(…)

In contrast to traditional presentations, I have shown in my study of dictatorship that even the seventeenth-century authors of natural law understood the question of sovereignty to mean the question of the decision on the exception. This is particularly true of Samuel von Pufendorf. Everyone agrees that whenever antagonisms appear within a state, every party wants the general good-therein resides after all the bellum omnium contra omnes. But sovereignty (and thus the state itself) resides in deciding this controversy, that is, in determining definitively what constitutes public order and security, in determining when they are disturbed, and so on. Public order and security manifest themselves very differently in reality, depending on whether a militaristic bureaucracy, a self-governing body controlled by the spirit of commercialism, or a radical party organization decides when there is order and security and when it is threatened or disturbed. After all, every legal order is based on a decision, and also the concept of the legal order, which is applied as something self evident, contains within it the contrast of the two distinct elements of the juristic-norm and decision. Like every other order, the legal order rests on a decision and not on a norm.

(…)

3. Political Theology

All significant concepts of the modern theory of the state are secularized theological concepts not only because of their historical development – in which they were transferred from theology to the theory of the state, whereby, for example, the omnipotent God became the omnipotent lawgiver-but also because of their systematic structure, the recognition of which is necessary for a sociological consideration of these concepts. The exception in jurisprudence is analogous to the miracle in theology. Only by being aware of this analogy can we appreciate the manner in which the philosophical ideas of the state developed in the last centuries.

(…)

Conclusion

Although Schmitt’s thought has influenced broader conservative and even some leftist critiques of liberalism, his primary focus on authority and nationalism firmly roots him as an authoritarian conservative.

Questions for reflection

1. How does Carl Schmitt’s concept of the friend-enemy distinction explain the intensification of political polarization in contemporary democracies, such as the divide between progressive and conservative factions on social media platforms?

2. How does the Schmittian concept of sovereignty as “he who decides on the exception” manifest in contemporary democracies during crises such as pandemics, terrorism, or climate emergencies?

3. How does Schmitt’s concept of “permanent emergency” manifest in regimes that normalize exceptional powers, transforming temporary measures into permanent tools of political control?

4. How does Carl Schmitt’s friend-enemy distinction critique the Brazilian Supreme Court’s portrayal of dissenters and misinformation spreaders as existential threats to institutions, justifying rights infringements?

5. Does the judicial overreach by figures like Justice Alexandre de Moraes in Brazil exemplify Schmitt’s warning about the depoliticization of liberalism leading to disguised authoritarianism in the name of institutional protection?

6. To what extent do the actions of Brazilian STF minister Alexandre de Moraes exemplify the use of the Schmittian state of exception to silence political opponents under the pretext of defending democracy?

7. Applying Schmitt’s concept of sovereignty, is the Brazilian judiciary’s suppression of free speech rights a manifestation of deciding on the exception, masked as safeguarding democratic norms?

8. How might Schmitt’s ideas on political homogeneity explain the Brazilian courts’ efforts to enforce narrative control and censor opposition, presented as a defense against threats to national institutions?

9. How does Bolsonaro’s trial by the Brazilian STF illustrate how the judiciary can assume the role of Schmittian sovereign, deciding who constitutes the political “enemy” and suspending normal constitutional guarantees?

10. To what extent do American sanctions against minister Alexandre de Moraes and his family demonstrate international tensions when a national judiciary applies Schmittian theories of exception against foreign citizens and institutions?

11. Does Schmitt’s association with the Third Reich—and the fact that he promoted these ideas while a party member—invalidate his concept of sovereignty or his broader political theory (as opposed to his personal actions and proposals)?

Leave a comment