Introduction

Joseph-Marie de Maistre (1753–1821) was a philosopher born in Chambéry in the Kingdom of Sardinia (now part of France). He is widely regarded as one of the founding figures of European conservatism and counter-revolutionary thought, particularly in opposition to the Enlightenment and the French Revolution.

Figure: Joseph-Marie de Maistre

Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Jmaistre.jpg

Active during the Napoleonic era and subsequent Restoration, Maistre witnessed the revolutionary upheaval that shattered traditional European order and devoted considerable intellectual energy to defending hierarchy, monarchy, and clerical authority as necessary bulwarks against social disintegration.

| Saint Augustine’s Influence Saint Augustine (354–430) was a major influence on de Maistre, shaping his ideas about divine providence, history, human sinfulness, and the redemptive value of suffering. Augustine’s City of God supplied a model for reading historical disasters as components of God’s inscrutable plan—an approach de Maistre applied to the turmoil of the French Revolution. In the way Augustine interpreted Rome’s decline as evidence of providential control amid worldly collapse, de Maistre claimed the Revolution’s seemingly senseless violence revealed God’s hand, casting it as both punishment and a means to moral renewal. This intensification of Augustinian themes informed de Maistre’s account of original sin: he pushed Augustine’s teaching on human corruption further, depicting people as fundamentally depraved and in need of coercive authority to curb their passions rather than capable of improvement through reason or innate goodness. In his work, de Maistre defends the existence of evil as serving divine order, treating events such as executions and wars as instruments or rites ordained by God. In sum, Augustine enabled de Maistre to conceive history not as human progress but as the mysterious unfolding of divine will, bolstering his anti‑rationalist outlook. |

Main ideas

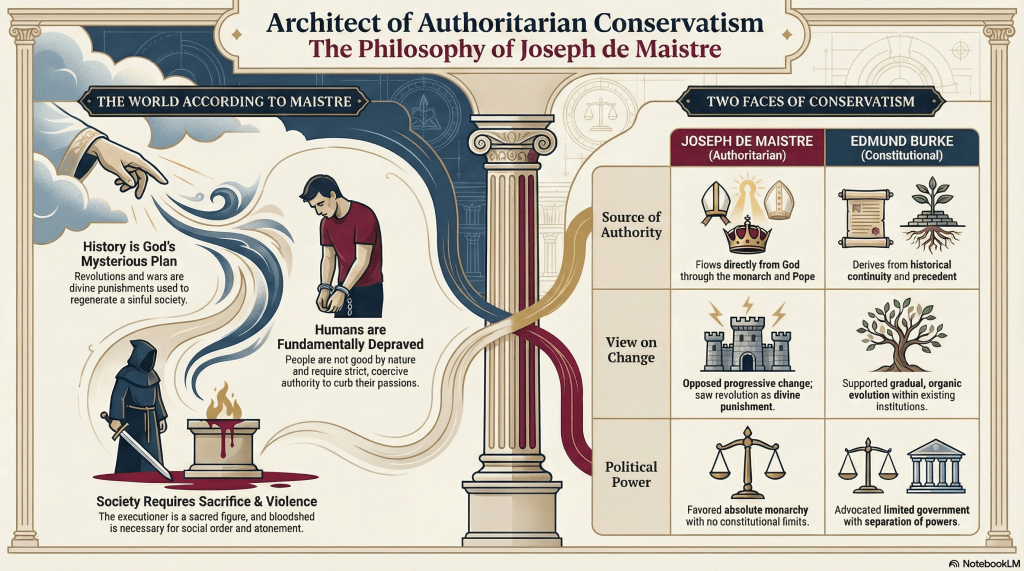

Maistre stands out as one of the most explicit and historically significant representatives of authoritarian conservative thought in European political philosophy. Unlike Burke, who defended tradition as the accumulated wisdom of generations and emphasized the continuity of constitutional liberty, Maistre advocated for explicit restoration of absolute monarchy.

Maistre’s fundamental difference from constitutional conservatism lies in his explicit rejection of limitations on executive power. While Burke argued that even monarchical rulers should moderate their power with timely reforms and act within constitutional limits, Maistre, on the other hand, envisioned kings exercising almost unrestricted will in the name of a higher, divinely ordained plan. He defended the concept of “Throne and Altar” as a direct response to the revolutionary cry of “Liberty, equality, fraternity” (and the practice of decapitated heads), endorsing a hierarchy with religious foundations to the detriment of popular sovereignty or constitutional mechanisms of control.

| Comparative Analysis: Joseph de Maistre and Edmund Burke Edmund Burke and Joseph de Maistre represent two distinct branches of conservative thought that emerged in response to Enlightenment ideology and the French Revolution. While both thinkers rejected revolutionary rationalism and championed tradition, their fundamental philosophical approaches diverged significantly, with Burke advocating constitutional conservatism rooted in evolutionary change, whereas Maistre championed authoritarian restoration grounded in divine providence and hierarchical order. | ||

| Dimension | Edmund Burke | Joseph de Maistre |

| Constitutional Framework | Defended parliamentary sovereignty and constitutional conventions; advocated limited government with separation of powers | Rejected constitutional procedures as products of destructive Enlightenment rationalism; favored absolute monarchy as divinely ordained |

| View of Social Change | Supported gradual, organic evolution within existing institutions. | Opposed progressive change entirely; saw the Revolution as divine punishment; believed constitutions emerge from God over time, not human creation. |

| Source of Authority | Authority derives from historical continuity, constitutional precedent, and parliamentary consent | Authority flows from God through the monarch and Pope; government power requires religious foundation, not logical explanation |

| Conception of Human Nature | Humans are driven by passion but capable of wisdom through inherited tradition and “prejudice” (latent wisdom) | Humans are naturally depraved and prone to disorder; require strict hierarchical control and religious discipline |

| Role of Religion | Burke praised Catholicism as a “barrier against radicalism” but maintained secular constitutional framework | Religion must be the foundation of all political power; papal authority should guide temporal governance |

| Approach to Aristocracy | Defended hereditary aristocracy as natural leadership within constitutional limits; subject to parliamentary accountability | Advocated restoration of absolute aristocratic privilege without constitutional restraint; nobility as divinely mandated class |

| Response to Revolution | Condemned revolutionary rationalism and bloodshed but maintained that legitimate grievances required reform | Viewed Revolution entirely as divine judgment and chaos; advocated complete restoration of ancien régime order. |

| Political Methodology | Opposed abstract theorizing; emphasized practical wisdom derived from historical experience | Developed rigorous logical defense of absolutism from accepted premises; created philosophical system justifying throne and altar. |

| Legacy and Influence | Became foundation of constitutional conservatism in Britain and America; influenced moderate conservatives | Influenced authoritarian and reactionary movements |

De Maistre’s philosophy emphasized hierarchy, tradition, divine providence, and the rejection of rationalist individualism. He viewed society as an organic, divinely ordained structure rather than a product of human reason or social contracts. Here are his key concepts:

- Providentialism and Divine Intervention in History: De Maistre argued that historical events, including revolutions and wars, are part of God’s plan. In his most famous work, Considerations on France (1797), he portrayed the French Revolution not as a triumph of liberty but as a divine punishment for France’s sins, such as its embrace of atheism and Enlightenment ideas. He believed that God uses violence and suffering to restore order, famously stating that “the Revolution is satanic” but ultimately serves a higher purpose.

- Authority and Hierarchy: He opposed democratic equality and individualism, insisting that true authority comes from God and is channeled through traditional institutions like the monarchy and the Church. He advocated for the absolute supremacy of the Pope over national churches and secular rulers. De Maistre saw society as naturally hierarchical, with the masses needing strong, paternalistic leadership to prevent chaos.

- The Role of Sacrifice and Violence: One of his more provocative ideas was that human society requires bloodshed and sacrifice to function. He viewed the executioner (hangman) as a sacred figure upholding social order, and war as a necessary outlet for human sinfulness. This stemmed from his belief in original sin: humanity is inherently flawed, and only through suffering and atonement can redemption occur.

- Critique of Enlightenment Rationalism: De Maistre rejected the Enlightenment’s faith in reason, progress, and universal rights. He mocked philosophers like Voltaire and Rousseau, arguing that their ideas led to moral decay and social upheaval. Instead, he championed faith, mystery, and tradition as the foundations of civilization. Knowledge, for him, was not derived from empirical science but from divine revelation and inherited wisdom.

- Conservatism and Restoration: His thought laid groundwork for reactionary politics, emphasizing the restoration of pre-revolutionary order. To him, progress is illusory and that true stability comes from submission to divine will.

| René Girard on Violence as foundational to Social Order René Girard (1923–2015), a Franco-American philosopher and anthropologist, developed theories on mimetic desire, scapegoating, and the role of violence in the foundation of social order. Girard’s fundamental idea is that human desire is not autonomous or original, but imitative (mimetic). We do not inherently desire objects; instead, we mold our desires according to those of others—our “models” or “mediators.” In his mimetic theory, he agreed with Joseph de Maistre that sacrifice is fundamental to social order, considering it a mechanism for resolving mimetic crises by redirecting violence to a substitute victim. He praised de Maistre as a pioneering thinker who recognized the role of sacrifice in containing social violence, anticipating his own scapegoat theory. Two quotes from Girard: – “Joseph de Maistre was the first writer to argue that sacrifice is the basis of all social order; Maistre sees all political violence in terms of ritual massacre.” (From “A Genealogy of Violence and Religion” by Girard) – “The animals sacrificed were always those most valued for their usefulness: the most docile and innocent creatures, whose habits and instincts brought them closest to harmony with man. […] From the animal kingdom, those chosen as victims were, if we may use the expression, the most human in their nature.” (From “Violence and the Sacred“) |

Maistre’s political theology positioned the monarch as standing in a quasi-divine relationship to the nation, wielding authority not constrained by laws created through popular ratification but by the transcendent order of divine providence and historical necessity.

Final considerations

The practical consequences of Maistre’s thinking manifested themselves in his support for systems of government that concentrated power in the hands of a few, justified by claims of superior wisdom and moral authority. On the other hand, Maistre’s work demonstrates a crucial feature of authoritarian conservatism: the transformation of conservative skepticism toward radical change into an affirmative defense of concentrated personal authority as the means of preserving social hierarchyal and religious foundations of order.

| Once a revolution begins, no one controls it anymore. One of Maistre’s most important ideas (though it is not always properly considered as such) is that, once a revolution begins, the revolutionaries have no power over the sequence of events. They are mere pawns, mechanically playing an uncontrollable game: The most striking thing about the French Revolution is this overwhelming force that bends every obstacle. It is a whirlwind carrying along like light straw everything that human force has opposed to it; no one has hindered its course with impunity. Purity of motives has been able to make resistance honourable, but no more, and this jealous force, proceeding straight toward its goal, rejects equally Charette, Dumouriez, and Drouet. It has been correctly pointed out that the French Revolution leads men more than men lead it. This observation is completely justified, and although it can be applied to all great revolutions more or less, it has never been more striking than it is in the present period. The very rascals who appear to lead the Revolution are involved only as simple instruments, and as soon as they aspire to dominate it they fall ignobly. Those who established the Republic did it without wanting to and without knowing what they were doing. They were led to it by events; a prior design would not have succeeded. Robespierre, Collot, or Barére never thought to establish the revolutionary government or the Reign of Terror; they were led to it imperceptibly by circumstances, and the like will never be seen again. These extremely mediocre men exercised over a guilty nation the most frightful despotism in history, and surely they were more surprised at their power than anyone else in the kingdom.’ (…) We are often astonished that the most mediocre men have been better judges of the French Revolution than men of first-rate talent, that they have believed in it completely while accomplished politicians have not believed in it at all. This is because this belief is one of the characteristics of the Revolution, because the Revolution could succeed only by the scope and power of the revolutionary spirit, or, if one may put it another way, by faith in the Revolution. Thus, untalented and ignorant men have very ably driven what they call the revolutionary chariot. They have dared everything without fear of counter-revolution; they have always gone ahead without looking back, and everything has succeeded for them because they were only the instruments of a force that knew more than they did. They made no mistakes in their revolutionary career for the same reason that Vaucanson’s flutist never hit a false note. The revolutionary torrent took successively different directions, and it was only by following the course of the moment that the most conspicuous men in the Revolution acquired the kind of power and celebrity they were able to achieve. As soon as they wanted to oppose it, or even to stand aside by isolating themselves or by working too much for themselves, they disappeared from the scene. (…) In short, the more one examines the apparently most active personages in the Revolution, the more one finds in them something passive and mechanical. We cannot repeat too often that men do not lead the Revolution; it is the Revolution that uses men. They are right when they say it goes all alone. This phrase means that never has the Divinity shown itself so clearly in any human event. If the vilest instruments are employed, punishment is for the sake of regeneration. (Joseph de Maistre. CONSIDERATIONS ON FRANCE. 1974.) |

Selected texts

Joseph de Maistre. CONSIDERATIONS ON FRANCE. Translated by Richard A. Lebrun. McGill-Queen’s University Press: Montreal and London 1974.

I. Of Revolutions

We are all attached to the throne of the Supreme Being by a supple chain that restrains us without enslaving us. Nothing is more admirable in the universal order of things than the action of free beings under the divine hand. Freely slaves, to they act voluntarily and necessarily at the same time; they really do what they will, but without being able to disturb the general plans. Each of these beings occupies the centre of a sphere of activity whose diameter varies according of the Eternal Geometer, who can extend, the restrict, will check, or direct the will without altering its nature.

In the works of man, everything is as wretched as their author; views are restricted, means rigid, motives inflexible, movements painful, and results monotonous. In divine works, the riches of infinity are openly displayed in the least part. Its power is exercised effortlessly; everything is supple in its hands, nothing resists it, and for it everything, even obstacles, are means; and the irregularities introduced by the operation of free agents fit into the general order. If we imagine a watch all of whose springs vary continually in strength, weight, dimension, form, and position that nevertheless invariably keeps perfect time, we will form some idea of the action of free beings relative to the plans of the Creator.

In the political and moral world, as in the physical world, there is a usual order and there are exceptions to this order. Ordinarily, we see series of effects produced by the same causes; but in certain epochs, we see actions suspended, causes paralysed, and new effects.

(…)

II. Reflections on the Ways of Providence in the French Revolution

(…)

An assault against sovereignty is undoubtedly one of the greatest crimes that can be committed; none has more terrible consequences. If sovereignty rests on a single head and that head falls victim to the assault, the crime is augmented by atrocity. But if this sovereign had committed no crime meriting such an attack, if the guilty were armed against him by his very virtues, the crime becomes unspeakable. We recognize here the death of Louis XVI. But what is important to note is that never has a greater crime had more accomplices. Far fewer were involved in the death of Charles I, even though he merited some blame and reproach and Louis XVI did not. Nevertheless he was given proofs of the most devoted courageous concern; even the executioner, who was only obeying orders, dared not reveal his identity. In France, Louis XVI marched to his death surrounded by 60,000 armed men who had not a shot for Santerre; not a voice was raised for the unfortunate monarch, and the provinces were as mute as the capital. We would expose ourselves, they said. Frenchmen! If you find this a good reason, talk no more of your courage, or admit that you have used it very badly.

(…)

In a word, if there is no moral revolution in Europe, if the religious spirit is not reinforced in this part of the world, the social bond will dissolve. Nothing can be predicted, and anything must be expected, but if there is to be improvement in this matter, either France is called upon to produce it, or there is no analogy, no more induction, no more art of prediction.

(…)

II. On the Violent Destruction of the Human Species

(…)

I will not carry this frightful catalogue any further; our own century and the preceding one are too well known. If you go back to the birth of nations, if you come down to our own day, if you examine peoples in all possible conditions from the state of barbarism to the most advanced civilization, you always find war. From this primary cause, and from all the other connected causes, the effusion of human blood has never ceased in the world. Sometimes blood flows less abundantly over some larger area, sometimes it flows more abundantly in a more restricted area, but the flow remains nearly constant.

But from time to time the flow is augmented prodigiously by such extraordinary events as the Punic Wars, the ‘Triumvirate, the victories of Caesar, the irruption of the barbarians, the Crusades, the wars of religion, the Spanish Succession, the French Revolution, etc. If one had a table of massacres similar to a meteorological table, who knows whether, after centuries of observation, some law might not be discovered? Buffon has proven quite clearly that a large percentage of animals are destined to die a violent death. He could apparently have extended the demonstration to man; but let the facts speak for themselves.

Yet there is room to doubt whether this violent destruction is, in general, such a great evil as is believed; at least, it is one of those evils that enters into an order of things where everything is violent and against nature, and that produces compensations. First, when the human soul has strength through laziness, incredulity, and the gangrenous vices that follow an excess of civilization, it can be retempered only in blood. Certainly there is no easy explanation of why war produces different effects in different circumstances. But it can be seen clearly enough that mankind may be considered as a tree which an invisible hand is continually pruning and which often profits from the operation. In truth the tree may perish if the trunk is cut or if the tree is overpruned; but who knows the limits of the human tree? What we do know is that excessive carnage is often allied with excessive population, as was seen especially in the ancient Greek republics and in Spain under the Arab domination. Platitudes about war mean nothing.

(…)

IV. Can the French Republic Last?

(…)

For example, what is peculiar and new about the three powers that constitute the government of England? The names of the Peers and the Commons, the costumes of the lords, etc. But the three powers, considered in the abstract, are to be found wherever a wise and lasting liberty is to be found; above all, they were found in Sparta, where the government, before Lycurgus, ‘was always in oscillation, inclining at one time to tyranny when the kings had too much power and at another time to popular confusion when the common people had usurped too much authority’. But Lycurgus placed the senate between the two, so that it was, according to Plato, ‘a salutary counterweight …and a strong barrier holding the two extremities in equal balance and giving a firm and assured foundation to the health of the state, because the senators . . . ranged themselves on the side of the king when there was need to resist popular temerity, and on the other hand, just as strongly took the part of the people against the king to prevent the latter from usurping a tyrannical power’.?

Thus, nothing is new, and a large republic is impossible, since there has never been a large republic.

(…)

V. The French Revolution Considered in Its Antireligious Character

Digression on Christianity

There is a satanic quality to the French Revolution that distinguishes it from everything we have ever seen or anything we are ever likely to see in the future. Recall the great assemblies, Robespierre’s speech against the priesthood, the solemn apostasy of the clergy, the desecration of objects of worship, the installation of the goddess of reason, and that multitude of extraordinary actions by which the provinces sought to outdo Paris. All this goes beyond the ordinary circle of crime and seems to belong to another world.

Even now, when the Revolution has become less violent, and wanton excesses have disappeared, the principles remain. Have not the legislators (I use their term) passed the historically unique rule that the nation will support no form of worship? Some of our contemporaries, it seems to me, have at certain moments reached the point of hating the Divinity; but this frightful act of violence was not necessary to render the very greatest creative efforts useless. The mere omission (let alone contempt) of the great Being in any human endeavour brands it with an irrevocable anathema. Either every imaginable institution is founded on a religious concept or it is only a passing phenomenon. Institutions are strong and durable to the degree that they are, so to speak, deified. Not only is human reason, or what is ignorantly called philosophy, incapable of supplying these foundations, which with equal ignorance are called superstitious, but philosophy is, on the contrary, an essentially disruptive force.

In short, man cannot act the Creator without putting himself in harmony with Him. Mad as we are, if we want a mirror to reflect the image of the sun, would we turn it towards the earth?

(…)

VI. On Divine Influence in Political Constitutions

(…)

All free constitutions known to men have been formed in one of two ways. Sometimes they have germinated, as it were, in an unconscious manner through the conjunction of a multitude of so-called fortuitous circumstances, and sometimes they have a single author, who appears like a sport of nature and enforces obedience. In either case, here are the signs by which God warns us of our weakness and of the rights that He has reserved to Himself in the formation of governments:

1. No constitution is the result of deliberation.The rights of the people are never written, or at any rate, constitutive acts fundamental written laws are never more than declaratory statements of anterior rights about which nothing can be said except that they exist because they exist.

2. God, not having judged it appropriate to use supernatural means in this area, has at least so far circumscribed human action that in the formation of constitutions circumstances do everything and men are only part of the circumstances. Commonly enough, even in pursuing one goal they attain another, as we have seen in the English constitution.

3. The rights of the people, properly so called, often enough proceed from the concessions of sovereigns and in this case can be verified historically; but the rights of the monarch and the aristocracy, at least their essential rights, which we may call constitutive and basic, have those neither date nor author.

4. Even these concessions of the sovereign have always been preceded by a state of affairs that made them necessary and that did not depend on him.

5. Although written laws are merely declarations of anterior rights, it is far from true that everything can be written down; in fact there are always some things in every constitution that cannot be written and that must be allowed to remain in dark and reverent obscurity on pain of upsetting the state.

6. The more that is written, the weaker the institution becomes, and the reason for this is clear. Laws are only declarations of rights, and rights are declared only when they are attacked, so that a multiplicity of written constitutional laws proves only a multiplicity of conflicts and the danger of destruction.

This is why the most vigorous political system of secular antiquity was that of Sparta, in which nothing was written.

(…)

X. On the Supposed Dangers of a Counter-Revolution

General Considerations

(…)

In order to effect the French Revolution, it was necessary to overthrow religion, outrage morality, violate every propriety, and commit every crime. This diabolical work required the employment of such a number of vicious men that perhaps never before had so many vices acted together to accomplish any evil whatsoever. In contrast, to restore order the king will call on all the virtues; no doubt he will wish to do this, but by the very nature of things he will be forced to do so. His most pressing interest will be to unite justice and mercy; honourable men will come of themselves to take up positions in posts where they can be of use, and religion, lending its authority to politics, will give the strength that can be drawn only from this august sister.

I have no doubt that many men will ask to be shown the bases of these magnificent hopes; but can we believe that the political world operates by chance, that it is not organized, directed, and animated by the same wisdom that is revealed in the physical world? The guilty hands that overthrow a state necessarily inflict grievous wounds, for no free agent can thwart the plans of the Creator without incurring in the sphere of his activity evils proportionate to the extent of the crime. This law pertains more to the goodness of the Supreme Being than to his justice.

But when man works to restore order he associates himself with the author of order; he is favoured by nature, that is to say, by the ensemble of secondary forces that are the agents of the Divinity. His action partakes of the divine; it becomes both gentle and imperious, forcing nothing yet not resisted by anything. His arrangements restore health. As he acts, he calms disquiet and the painful agitation that is the effect and symptom of disorder. In the same way, the hands of a skilful surgeon bring the cessation of pain that proves the dislocated joint has been put right.

(…)

Questions for reflection

1. Did the French Revolution emerge primarily from the pernicious influence of Enlightenment philosophy, as Maistre insisted, or did deep structural transformations in French society, economy, and political institutions create conditions that would have produced revolutionary upheaval regardless of philosophical currents?

2. If human beings are fundamentally emotional and prone to disorder and evil as Maistre contended, then how could such naturally flawed creatures ever successfully establish legitimate government in the first place?

3. To what extent are Maistre’s arguments for absolute monarchy logically dependent on Catholic theological premises, and could his political conclusions survive translation into secular frameworks?

4. If one accepts Maistre’s argument that effective governance requires concentrated authority capable of decisive action unbounded by constitutional procedure, does this logic necessarily justify the expansion of executive power observed across democratic nations in recent decades?

5. Maistre defended hierarchical society as natural and necessary; would he have viewed modern wealth inequality and class division as legitimate expressions of natural order, or as dangerous departures from properly constituted authority?

6. How does de Maistre’s concept of providentialism explain historical events like wars or revolutions, and does it offer a comforting or troubling view of human suffering?

7. In what ways does de Maistre’s defense of hierarchy and authority challenge modern democratic ideals, and could it justify authoritarian regimes today?

8. Consider the existence of the United States and what Alexander Hamilton wrote in Federalist Paper No. 1.

It has often been observed that it seems to have been reserved to the people of this country, by their conduct and example, to decide the important question of whether human societies are actually capable of establishing good government through reflection and choice, or whether they are forever destined to depend, for their political constitutions, on chance and force.

What to think of the following proposition by Maistre: Thus, nothing is new, and a great republic is impossible, since there never was a great republic.