Introduction

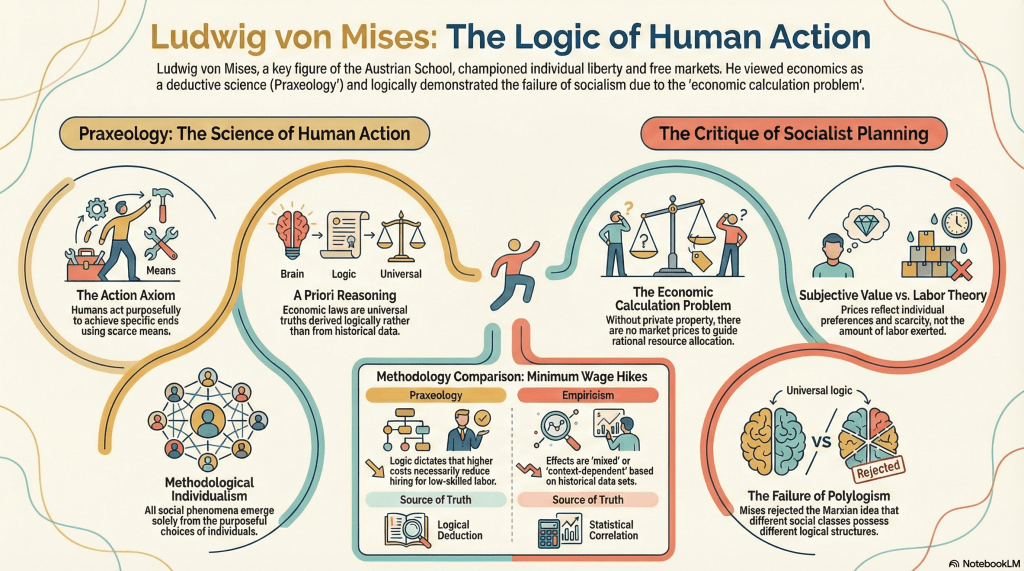

Ludwig von Mises (1881–1973) was an Austrian economist, and a leading figure of the Austrian School. Trained in Vienna, he served as a government advisor and later taught and wrote extensively, especially after emigrating to the United States during World War II. Mises combined rigorous theoretical argumentation with a vigorous defense of classical liberalism, championing individual liberty, private property, and free markets.

Figure. Ludwig von Mises

Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ludwig_von_Mises.jpg

Von Mises critics to Karl Marx ideas

Ludwig von Mises mounted a systematic critique of Marxism, arguing that socialism collapses on the “economic calculation problem”: without private ownership of the means of production there are no market prices for capital goods, so planners cannot make rational allocation decisions. He rejected the labor theory of value, proposing instead a subjective theory where prices reflect individual preferences, scarcity, and marginal utility; absent dynamic price signals, socialist decision-making becomes arbitrary, inefficient, and wasteful. Mises also defended entrepreneurship and capital accumulation as drivers of progress rather than forms of exploitation.

Beyond technical economics, Mises attacked Marxism’s philosophical and methodological foundations—historical materialism and dialectics—as deterministic and unscientific, and he promoted methodological individualism, holding that social outcomes arise from purposeful individual actions. He characterized Marxism as a utopian, quasi-religious ideology that ignores human uncertainty, time preference, and incentive structures, warning that market suppression and heavy intervention lead to distortions, increased boom–bust cycles (driven by monetary factors), and ultimately political coercion rather than emancipation.

Human Action

Human Action, Mises’ seminal 1949 treatise on economics, represents the culmination of his praxeological approach to understanding human behavior and society. Mises posits that economics is a subset of praxeology, the deductive science of human action, which starts from the irrefutable axiom that humans act purposefully to achieve ends using scarce means. He rejects empiricism and positivism in social sciences, arguing that economic laws are derived aprioristically from this axiom, much like geometry from basic postulates. Mises emphasizes methodological individualism, insisting that all social phenomena emerge from individual choices, and he dismantles collectivist ideologies by showing how they ignore the inherent uncertainty and dynamism of human decision-making.

| Praxeology vs. empirical analysis A praxeological analysis Starting from the core premise that individuals act to achieve ends using scarce means, we recognize that employers (as actors) seek to maximize utility by hiring labor only if the marginal productivity of that labor exceeds its cost. In a free market, wages emerge from voluntary exchanges reflecting subjective valuations: workers offer labor to satisfy their need for income, while employers bid based on anticipated revenue from the worker’s output. If a government imposes a minimum wage above the market-clearing level, this intervention disrupts the natural equilibrium. Deductively, since action implies choice amid scarcity, employers facing higher mandated costs will reduce hiring for lower-skilled workers whose productivity doesn’t justify the new wage, leading to involuntary unemployment. This isn’t an empirical prediction but a logical necessity derived from the structure of action—preferences for profit over loss and the impossibility of sustaining unprofitable exchanges without coercion.This praxeological approach contrasts with empirical methods by avoiding historical data or statistical correlations, instead revealing universal truths about interventionism. For instance, while some might observe short-term employment stability post-wage hike due to confounding factors like economic booms, praxeology shows that such policies inevitably cause discoordination: displaced workers crowd into unregulated sectors, suppressing wages there, or turn to black markets, while consumers face higher prices from increased production costs. Mises and followers like Murray Rothbard extend this to argue that minimum wages exemplify how state interference thwarts the spontaneous order of markets, reducing overall prosperity by overriding individual calculations of value and opportunity. Thus, praxeology not only critiques the policy but illuminates why capitalism fosters efficiency through unhampered human action. An empirical analysis An empirical analysis of minimum wage laws’ effects on employment relies on observational data, econometric models, and meta-analyses to estimate real-world impacts, often using difference-in-differences methods or time-series regressions to isolate causal effects amid confounding variables like economic cycles or labor market conditions. For instance, a comprehensive review of 21 studies since the 1990s found a median own-wage elasticity of employment near zero, with 90% of estimates indicating no or only small disemployment effects (ranging from -0.4 to positive values), suggesting that minimum wage hikes primarily boost earnings for low-wage workers without substantial job losses. (https://www.epi.org/blog/most-minimum-wage-studies-have-found-little-or-no-job-loss/) Historical data over seven decades in the US shows no clear correlation between federal minimum wage increases and overall employment declines, as basic indicators like unemployment rates remained stable or improved post-hikes. (https://www.nelp.org/insights-research/raise-wages-kill-jobs-no-correlation-minimum-wage-increases-employment-levels/) However, some studies targeting vulnerable groups like teens or low-skilled workers report negative effects; a 2012 analysis of New York’s 2004-2006 increase from $5.15 to $6.75 estimated a 20.2-21.8% reduction in employment for less-educated young adults. (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Minimum_wage_in_the_United_States). Statistically, meta-analyses indicate an average elasticity of around -0.1 to -0.2 for teens: for a 10% wage hike, this implies a 1-2% employment drop. Using code to simulate: if elasticity = -0.15 and wage increase = 20% (e.g., from $7.25 to $8.70), expected employment change = -0.15 * 20% = -3%, potentially affecting thousands in low-skill sectors based on BLS data showing about 1.1 million minimum wage workers in 2023. (https://www.bls.gov/opub/reports/minimum-wage/2023/) Yet, results vary by context—faster increases during recessions amplify disemployment, per NBER research on the Great Recession. (https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w20724/w20724.pdf) A contrast between the methodologies. In contrast to praxeological analysis, which deductively concludes from the axiom of action that any minimum wage above market equilibrium levels necessarily causes involuntary unemployment, making some labor exchanges unprofitable, empirical methods produce mixed and context-dependent results that do not always manage to “falsify” the “universal” laws deduced a priori due to the complexity of historical data. |

In Human Action, Mises advocate for free market capitalism as the only system compatible with rational resource allocation and human freedom. He warns against government interventions like price controls or monetary manipulation, which distort signals and lead to malinvestments, as seen in his business cycle theory. The work also delves into epistemology, ethics, and history, portraying economics not as a narrow field but as essential to comprehending civilization’s progress through voluntary cooperation and division of labor.

| Explaining revolutions From a praxeological perspective, revolutions emerge as the aggregated result of purposeful human actions aimed at alleviating perceived uneasiness in a world of scarcity and uncertainty. Starting from the action axiom—that individuals act deliberately to substitute a more satisfactory state for a less satisfactory one—we deduce that participants in a revolution, such as the Cuban Revolution of 1953–1959, perceive the existing regime (e.g., Batista’s government) as imposing costs (oppression, economic distortions via interventionism, restricted opportunities) that exceed the benefits of compliance. Revolutionaries like Fidel Castro and supporters choose means—guerrilla warfare, mobilization, and ideological propagation—to achieve ends: overthrowing the regime to establish a system they anticipate will better satisfy preferences, such as greater equality or autonomy. This involves time preference (valuing present action despite future risks), subjective valuation (weighing personal gains against losses like violence), and entrepreneurial alertness to opportunities for change. Deductively, without empirical testing, revolutions cannot succeed without voluntary cooperation among actors, as coerced systems (e.g., post-revolutionary statism) distort rational calculation, leading to inefficiency; thus, true revolutions favoring liberty enhance social coordination, while those imposing collectivism inevitably fail due to the absence of market prices for resource allocation. In comparison, Tanter and Midlarsky’s theory in “A Theory of Revolution” (https://www.researchgate.net/publication/43117201_A_theory_of_revolution) adopts an empirical, inductive approach, categorizing revolutions into types (mass revolution, revolutionary coup, reform coup, palace revolution) based on observable traits like mass participation, duration, domestic violence, and insurgent intentions, then correlating these with aggregates such as GNP per capita growth rates, educational attainment, and land inequality (via Gini indices). Their findings highlight regional variances—e.g., Asian revolutions show strong positive links between prior economic growth and violence, supporting Davies’ J-curve (long-term achievement followed by reversal creating a “revolutionary gap” between aspirations and expectations), while Latin American palace revolutions are decoupled due to class barriers. Praxeology critiques this as methodologically flawed, rejecting aggregate data and statistical correlations for deriving universal laws, as historical events are unique and complex, not falsifiable like natural science; instead, it views revolutions through individual purposeful choices, dismissing psychological constructs like aspirations/expectations as unnecessary, since action itself implies preference and valuation. Where Tanter and Midlarsky offer testable hypotheses and typologies to explain patterns (e.g., lower education correlating with higher violence in Asia), praxeology provides apodictic certainty that revolutions stem from interventions disrupting voluntary exchange, without needing regional or empirical qualifiers. For instance, while praxeology might generically attribute revolutions to state interventions disrupting voluntary exchanges, it offers no mechanism to predict or differentiate their intensity, duration, or forms, rendering it philosophically intriguing but practically inert for dissecting complex events. In contrast, the usefulness of Tanter and Midlarsky’s empirical theory highlights praxeology’s shortcomings by demonstrating how inductive analysis, grounded in data like GNP per capita growth rates, educational enrollment ratios, and Gini indices of land inequality, yields testable hypotheses and actionable insights into revolutionary causes. Their typology—distinguishing mass revolutions from coups based on measurable traits like domestic violence and duration—reveals regional patterns, such as strong correlations between pre-revolution economic upswings (followed by reversals, per Davies’ J-curve) and violence in Asia/Middle East, versus decoupling in Latin America’s class-rigid palace revolutions. This approach not only validates or refines theories through correlation coefficients (e.g., r = .94 for GNP/capita and violence in Asia) but also suggests policy implications, like addressing inequalities to mitigate revolutionary gaps, making it far more adaptable and predictive than praxeology’s static axioms, which dismiss such empirics as mere historical interpretation without deriving falsifiable laws. |

His monetary–business-cycle theory linked credit expansion and interest-rate manipulation to economic booms and busts. Influential to thinkers such as Friedrich Hayek and later libertarians, Mises’s work remains controversial: admired for its defense of liberal institutions and market coordination, but criticized for its aprioristic method and limited engagement with empirical and institutional complexities.

Influence and Legacy

Mises’ praxeology has profoundly shaped the Austrian School, promoting laissez-faire policies and individual liberty by illustrating how free markets enable rational calculation and coordination. Even in non-Austrian contexts, elements appear in behavioral economics and philosophy of action. Today, it remains a cornerstone for those advocating methodological individualism and skepticism toward empirical overreach in social sciences.

Selected texts

LUDWIG VON MISES. HUMAN ACTION. A Treatise On Economics. FOURTH REVISED EDITION. Fox & Wilkes

(…)

III. ECONOMICS AND THE REVOLT AGAINST REASON

1. The Revolt Against Reason

(…)

Then there was the long line of utopian authors. They drafted schemes for an earthly paradise in which pure reason alone should rule. They failed to realize that what they called absolute reason and manifest truth was the fancy of their own minds. They blithely arrogated to themselves infallibility and often advocated intolerance, the violent oppression of all dissenters and heretics. They aimed at dictatorship either for themselves or for men who would accurately put their plans into execution. There was, in their opinion, no other salvation for suffering mankind.

(…)

The great upheaval was born out of the historical situation existing in the middle of the nineteenth century. The economists had entirely demolished the fantastic delusions of the socialist utopians. The deficiencies of the classical system prevented them from comprehending why every socialist plan must be unrealizable; but they knew enough to demonstrate the futility of all socialist schemes produced up to their time. The communist ideas were done for. The socialists were absolutely unable to raise any objection to the devastating criticism of their schemes and to advance any argument in their favor. It seemed as if socialism was dead forever.

Only one way could lead the socialists out of this impasse. They could attack logic and reason and substitute mystical intuition for ratiocination. It was the historical role of Karl Marx to propose this solution. (…)

There was still the main obstacle to overcome: the devastating criticism of the economists. Marx had a solution at hand. Human reason, he asserted, is constitutionally unfitted to find truth. The logical structure of mind is different with various social classes. There is no such thing as a universally valid logic. What mind produces can never be anything but “ideology,” that is, in the Marxian terminology, a set of ideas disguising the selfish interests of the thinker’s own social class. Hence, the “bourgeois” mind of the economists is utterly incapable of producing more than an apology for capitalism. The teachings of “bourgeois” science, an offshoot of “bourgeois” logic, are of no avail for the proletarians, the rising class destined to abolish all classes and to convert the earth into a Garden of Eden.

But, of course, the logic of the proletarians is not merely a class logic. “The ideas of proletarian logic are not party ideas, but emanations of logic pure and simple.” Moreover, by virtue of a special privilege, the logic of certain elect bourgeois is not tainted with the original sin of being bourgeois. Karl Marx, the son of a well-to-do lawyer, married to the daughter of a Prussian noble, and his collaborator Frederick Engels, a wealthy textile manufacturer, never doubted that they themselves were above the law and, notwithstanding their bourgeois background, were endowed with the power to discover absolute truth.

It is the task of history to describe the historical conditions which made such a crude doctrine popular. Economics has another task. It must analyze both Marxian polylogism and the other brands of polylogism formed after its pattern, and expose their fallacies and contradictions.

2. The Logical Aspect of Polylogism

Marxian polylogism asserts that the logical structure of the mind is different with the members of various social classes. Racial polylogism differs from Marxian polylogism only in so far as it ascribes to each race a

peculiar logical structure of mind and maintains that all members of a definite race, no matter what their class affiliation may be, are endowed with this peculiar logical structure.

There is no need to enter here into a critique of the concepts social class and race as applied by these doctrines. It is not necessary to ask the Marxians when and how a proletarian who succeeds in joining the ranks of the bourgeoisie changes his proletarian mind into a bourgeois mind. It is superfluous to ask the

racists to explain what kind of logic is peculiar to people who are not of pure racial stock. There are much more serious objections to be raised.

Neither the Marxians nor the racists nor the supporters of any other brand of polylogism ever went further than to declare that the logical structure of mind is different with various classes, races, or nations. They never ventured to demonstrate precisely in what the logic of the proletarians differs from the logic of the bourgeois, or in what the logic of the Aryans differs from the logic of the non-Aryans, or the logic of the Germans from the logic of the French or the British. In the eyes of the Marxians the Ricardian theory of comparative cost is spurious because Ricardo was a bourgeois. The German racists condemn the same theory because Ricardo was a Jew, and the German nationalists because he was an Englishman. Some German professors advanced all these three arguments together against the validity of Ricardo’s teachings. However, it is not enough to reject a theory wholesale by unmasking the background of its author. What is wanted is first to expound a system of logic different from that applied by the criticized author. Then it would be necessary to examine the contested theory point by point and to show where in its reasoning inferences are made which—although correct from the point of view of its author’s logic—are invalid from the point of view of the proletarian, Aryan, or German logic. And finally. it should be explained what kind of conclusions the replacement of the author’s vicious inferences by the correct inferences of the critic’s own logic must lead to. As everybody knows, this never has been and never can be attempted by anybody.

(…)

A consistent supporter of polylogism would have to maintain that ideas are correct because their author is a member of the right class, nation, or race. But consistency is not one of their virtues. Thus the Marxians are prepared to assign the epithet “proletarian thinker” to everybody whose doctrines they approve. All the others they disparage either as foes of their class or as social traitors. Hitler was even frank enough to admit that the only method available for him to sift the true Germans from the mongrels and the aliens was to enunciate a genuinely German program and to see who were ready to support it. A dark-haired man whose bodily features by no means fitted the prototype of the fair-haired Aryan master race, arrogated to himself the gift of discovering the only doctrine adequate to the German mind and of expelling from the ranks of the Germans all those who did not accept this doctrine whatever their bodily characteristics might be. No further proof is needed of the insincerity of the whole doctrine.

(…)

Questions for reflection

1. Imagine yourself as a scientist studying a social phenomenon. Even if you are not an economist of the Austrian school and you believe in the need to validate conclusions through historical data and econometric analyses, would a praxeological analysis at least be a good starting point?

2. What were Mises’s fundamental objections to socialist economic systems, and do those critiques remain relevant to modern discussions about centralized economic planning? Do you believe that the development of AI will change this?

3. How might Mises’ critique of central planning apply to contemporary issues like government-mandated green energy transitions and their economic inefficiencies?

4. How do Mises’ warnings about the dangers of credit expansion relate to the modern housing bubbles and financial crises, such as the 2008 recession?

5. What insights from Mises’ theory of socialism could explain the economic failures seen in modern examples like Venezuela or Cuba?

6. Considering Mises’ advocacy for classical liberalism, how would his ideas critique current debates over universal basic income or expansive welfare states in developed nations?

7. How applicable is Mises’s economic reasoning to emerging economic challenges like automation, globalization, or climate-related economic transitions?

Leave a comment