Introduction

Friedrich Hayek stands as one of the most influential intellectual figures of the twentieth century, whose work fundamentally reshaped modern economic and political thought through his defense of individual liberty, free markets, and decentralized decision-making. Hayek’s contributions span economics, philosophy, law, and social theory, unified by a single concern: understanding how complex social orders emerge without centralized direction and how human freedom can be preserved against the encroaching power of the state. His critique of socialism proved prescient as the twentieth century unfolded, while his proposals for constitutional reorganization continue to inspire scholars and policymakers seeking to limit governmental power and protect individual rights.

Figure 32: Friedrich Hayek.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Friedrich_Hayek_portrait.jpg

Spontaneous Order and the Price Mechanism as Coordinating Systems

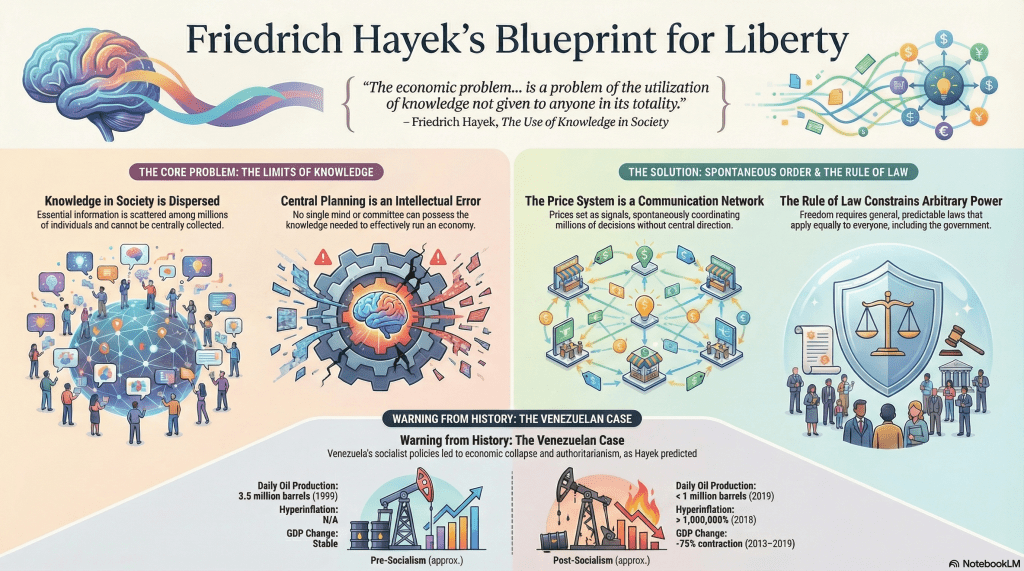

Friedrich Hayek argued that the price system is a spontaneous order arising from millions of independent decisions rather than from central design. Because knowledge in society is widely dispersed—held as local, situational, and specialist information—prices act as a decentralized communication network, encoding scarcity and opportunity so individuals can make sensible choices without knowing the whole economy. This mechanism coordinates production and consumption efficiently: rising prices signal shortages and prompt increased production and reduced demand, accomplishing a level of coordination no central planner could match.

Hayek emphasized that markets are not technically perfect, but they outperform any feasible alternative because no single mind or bureaucracy can aggregate dispersed information as markets do. His insight addressed the economic calculation problem of socialism and framed a broader social philosophy: many complex institutions (language, law, culture) evolve organically, and attempts at comprehensive rational design of such systems inevitably reduce effectiveness and freedom.

| Similarities between F. Hayek and J. Locke in their theories of law. Friedrich Hayek’s concept of law as originating from spontaneous order posits that legal rules emerge organically from the decentralized, evolutionary interactions of individuals, without central planning, forming a complex system that adapts over time through trial and error. In contrast, John Locke’s state of nature describes a hypothetical pre-governmental condition where individuals are free and equal under natural law—rational principles derived from reason or divine endowment—governing behavior to prevent harm, though lacking enforced structure leads to inconveniences. Although the structures diverge in origins, epistemology, and some implications for government, they share many similarities: Pre-Existing Order Independent of Centralized Authority: Both recognize a form of law or order that precedes formal government. For Locke, natural law in the state of nature provides moral guidelines for equal, free individuals, protecting life, liberty, and property without a sovereign. Similarly, Hayek views law as part of a spontaneous order arising from individual actions and customs, not imposed top-down. Necessity of Law for Freedom: Hayek explicitly endorses Locke’s dictum that “where there is no law there is no freedom,” arguing that rules are essential to limit coercion and enable individuals to pursue their goals securely. Both see law as safeguarding liberty from arbitrary interference by others. Roots in Natural Law Tradition: Hayek aligns with the Natural Law framework, which includes Locke, emphasizing natural tendencies toward order, harmony, and the protection of rights like property. Both view these orders as beneficial for societal coordination and individual well-being, with property as a key evolved or natural institution. Protection Against Insecurity: Locke’s state of nature highlights vulnerabilities where unrestricted liberty can lead to domination without protection, necessitating structured enforcement. Hayek’s spontaneous order similarly addresses coordination through rules that reduce coercion, promoting negative liberty (absence of interference). |

Austrian Business Cycle Theory and Monetary Policy Critique

Hayek, following Mises, explained business cycles as the result of government-induced distortions in money and credit rather than inherent market failures. Central banks that push interest rates below their market-clearing level mislead entrepreneurs into undertaking long-term, roundabout investments that are unbacked by real savings. This produces an artificial boom driven by “malinvestment” that must eventually be liquidated; the ensuing bust and painful reallocation of resources and labor are the market’s correction of those prior distortions.

The theory implies a policy critique of Keynesian stabilization: expansionary monetary policy causes rather than cures cycles. Because relevant economic knowledge is dispersed, central bankers cannot set the correct money supply or interest rate, and state control of money undermines savings, cooperation, and freedom. Hayek therefore recommended letting interest rates form in markets, constraining credit expansion, and even allowing competing private currencies to discipline monetary provision.

Hayek’s Devastating Critique of Central Planning and Socialism

Hayek’s central critique in The Road to Serfdom argues that socialist central planning, however well-intentioned, inevitably requires concentration of coercive power and destroys individual freedom. He contended that planning for material equality cannot be achieved democratically because consistent central direction demands suppressing private choices; the political logic of comprehensive planning therefore leads to authoritarian control to enforce the planners’ vision.

Economically, Hayek (building on Mises) formulated the economic calculation problem: knowledge is widely dispersed—local, tacit, and context-specific—so central planners cannot obtain the information or price signals necessary to allocate resources efficiently. Examples like agriculture show why many activities resist central coordination, and attempts to simulate market prices confuse market outcomes with the underlying coordinating process. Beyond inefficiency, Hayek diagnosed socialism as an intellectual error—“scientism”—that treats society as a machine to be designed, a stance that both fails practically and paves the way to totalitarianism.

| The Venezuelan case Venezuela, once South America’s richest nation due to its oil wealth, began deviating from Friedrich Hayek’s principles of limited government and free markets after Hugo Chávez’s 1998 election. Embracing “Bolivarian socialism,” Chávez rejected capitalist ideas, including Hayek’s warnings against central planning. Instead, the regime pursued nationalizations of key industries like oil and agriculture, imposed price controls, and expanded welfare programs funded by oil revenues. These actions ignored Hayek’s emphasis on secure property rights and market-driven price signals, which he argued are essential for coordinating dispersed knowledge and fostering spontaneous economic order.The economic fallout was swift and severe, aligning with Hayek’s predictions of inefficiency in planned systems. Oil production collapsed from 3.5 million barrels per day in 1999 to under 1 million by 2019 due to state mismanagement. Price controls led to chronic shortages of food and medicine, hyperinflation exceeding 1,000,000% in 2018, and a GDP contraction of about 75% from 2013 to 2019. Poverty surged above 90%, triggering mass emigration and a humanitarian crisis, as the government failed to adapt to falling oil prices—unlike other oil-dependent countries—due to its disregard for market mechanisms.As crises deepened, the regime under Chávez and successor Nicolás Maduro turned authoritarian to enforce failing policies, exemplifying Hayek’s thesis that planning requires coercion. Democratic institutions eroded: the constitution was amended to centralize power, opposition victories were overturned, and elections like Maduro’s 2018 win were rigged. Protests were violently suppressed, resulting in hundreds of deaths, while media censorship, political imprisonments, and military loyalty through patronage solidified control, transforming Venezuela from a democracy into a dictatorship.This trajectory directly illustrates Hayek’s warnings in The Road to Serfdom that well-intentioned interventions for equality lead to totalitarianism, as economic control demands suppression of freedoms. Venezuela’s alliances with authoritarian states and international isolation via sanctions further entrenched the regime, underscoring how ignoring Hayek’s advocacy for rule of law and decentralization can culminate in a self-perpetuating cycle of failure and oppression. |

The Rule of Law and Constitutional Safeguards for Liberty

Hayek argued that protecting liberty requires a strict rule of law: laws must be general, publicly preannounced, and knowable so they apply equally to all rather than through discretionary, ad hoc commands. This predictability and impartiality constrain arbitrary power and allow individuals to plan their lives; by contrast, discretionary rule—whether by monarchs, officials, or transient majorities—undermines freedom because it subjects people to unpredictable interventions.

From this foundation Hayek defended constitutional constraints and limited government: the state’s proper role is to set general rules that protect property, enforce contracts, and preserve competition, not to pursue substantive social goals or grant special privileges. He favored institutional checks—separation of powers, federalism, and judicial safeguards—to prevent concentration of authority and majoritarian tyranny, and warned that twentieth‑century expansions of governmental discretion had weakened these protections and needed reinforcement.

Hayek rejected “social justice” as a coherent political objective, arguing that justice properly applies to general rules and procedures, not to market outcomes that arise spontaneously from millions of voluntary transactions. Calling market results “unjust” presumes a responsible agent who can and should enforce particular distributions; efforts to achieve distributive justice therefore require discretionary, case‑by‑case interventions that violate the rule of law’s requirements of generality, predictability, and equality before the law.

He extended this critique to meritocracy, noting that market rewards reflect consumers’ valuations, not some objective measure of moral worth, and that many determinants of success (inheritance, talent, luck) are unrelated to merit. To enforce a meritocratic distribution would demand constant state judgment and intervention—replacing general rules with arbitrary commands—and thus would obliterate the freedom the policy claims to honor; in Hayek’s view a merit‑enforcing state would be the opposite of a free society.

To prevent this erosion of liberty, Hayek proposed constitutional and legal reforms:

Bicameral Legislature: A two-chamber system where an upper house (elected by mature citizens, e.g., at age 45, for long terms) creates general, abstract laws that bind the lower house, which handles daily governance and specific policies. This separation prevents interest-group capture and ensures laws prioritize long-term freedom over short-term expediency.

Primacy of Common Law and Judicial Role: Emphasize evolved common law over statutory legislation, with judges protecting individual expectations and adapting rules through precedent. This counters the erosion of the rule of law by administrative discretion, requiring laws to be general, equal, and non-retroactive.

Limits on Government Power: Constitutional safeguards like bills of rights, separation of powers, and judicial review to prevent coercion and majority tyranny. Government should enforce contracts and property rights but avoid redistributive “social justice,” which conflicts with equal treatment under law and leads to arbitrary interventions.

Decentralization and Local Governance: Empower local governments for specific services, reducing central bureaucracy and allowing spontaneous orders to flourish at smaller scales.

Emergency Provisions and Compensation: Allow temporary government interventions in crises but require compensation for infringed rights, maintaining accountability.

These reforms aim to create a “constitution of liberty” that protects individual spheres from interference, counters the welfare state’s expansion, and ensures democracy aligns with liberal principles.

| Constitutional Economics Inspired by Hayek’s ideas and based on public choice theory, James McGill Buchanan Jr. (1919–2013) developed constitutional economics, which focuses on the “rules of the game” rather than day-to-day politics. It treats constitutions as social contracts that individuals would hypothetically accept to maximize mutual benefit and avoid domination or discrimination. This approach is normative and positive: it designs institutions to align self-interest with societal good while analyzing how rules evolve. Core elements: Contractarian Framework: Drawing from thinkers like John Rawls (though critically), Buchanan posited that legitimate rules emerge from unanimous or near-unanimous consent at the constitutional stage, where people are uncertain about their future positions (a “veil of uncertainty”). This ensures fairness and minimizes exploitation. Two-Stage Decision-Making: Distinguish between “constitutional rules” (broad, enduring frameworks like property rights or balanced budgets) and “post-constitutional choices” (specific policies). Strong constitutions limit discretionary power, preventing short-term political opportunism. Self-Governance and Liberty: Emphasizes voluntary exchange, self-determination, and protections against coercive majorities. For instance, fiscal rules like debt ceilings could curb deficit spending driven by public choice pathologies. Buchanan viewed constitutional economics as a modern “science of legislation,” akin to Adam Smith’s ideas, aimed at fostering cooperative societies without central planning. |

The Problem of Dispersed Knowledge and Democratic Governance

Hayek argued that because economically relevant knowledge is dispersed among millions of individuals and cannot be aggregated by any central authority, centralized political decision-making—whether socialist, fascist, or interventionist liberal—faces insurmountable informational limits. The problem is structural, not merely one of bad intentions or incompetence: no set of planners can obtain the local, tacit, and time‑specific knowledge needed to coordinate complex economic activity effectively.

From this follows a principle for organizing authority: decisions should be made where the necessary knowledge resides, so decentralization—letting individuals, families, localities, and private organizations decide most particular matters—yields better outcomes. Political institutions should therefore focus on establishing and enforcing general rules (property, contracts, basic conduct) rather than making targeted, case‑by‑case economic decisions; democracy is best understood as the mechanism for setting general principles, not for micromanaging specialized, localized choices.

| School voucher programs One example of a public policy aligned with Friedrich Hayek’s concept of dispersed knowledge—where information is fragmented across individuals and best coordinated through decentralized mechanisms like markets—and democratic governance is the implementation of school voucher programs, such as those adopted in various U.S. states like Wisconsin’s Milwaukee Parental Choice Program starting in 1990. In this policy, eligible families receive government-funded vouchers to send their children to private or charter schools of their choice, rather than being assigned to public schools based on centralized bureaucratic decisions. This aligns with Hayek’s dispersed knowledge by empowering parents, who possess unique, local insights into their child’s specific needs, learning style, and circumstances, to make educational choices. Instead of a central authority presuming to know what’s best for all students through uniform planning, the voucher system uses market-like competition among schools to reveal and aggregate this dispersed information via parental decisions, leading to more efficient resource allocation and innovation in education. Regarding democratic governance, the policy is enacted and overseen through elected legislatures and local school boards, reflecting Hayek’s view of democracy as a procedural framework for collective decision-making that respects individual liberty and limits coercive central power. It promotes a form of “democracy in action” by decentralizing control from federal or state bureaucracies to families and communities, fostering accountability through voter-approved reforms while avoiding the “pretense of knowledge” Hayek warned against in top-down systems. |

Contemporary Relevance and Modern Challenges

Hayek’s ideas, developed in response to twentieth-century debates about socialism and central planning, continued to demonstrate surprising relevance as the twenty-first century unfolded and new challenges emerged. The Mises Institute’s decision to distribute 100,000 free copies of Hayek for the 21st Century: Essays in Political Economy in 2025 reflected recognition that his core insights remained vital for understanding contemporary economic and political problems. Each of the seven chapters in this volume addresses contemporary issues including cryptocurrency and digital technologies, which some scholars argued represented implementations of Hayekian principles by enabling individuals to escape government currency monopolies and participate in decentralized monetary systems.

The persistence of inflation despite official monetary policy frameworks, the concentration of power in central banks and federal governments, and increasing frustration with bureaucratic regulation all suggested that Hayek’s warnings about the dangers of monetary manipulation and centralized planning retained urgent relevance for twenty-first century readers. Advocates of limited government and free markets invoked Hayekian arguments against proposed regulations, industrial policies, and redistributive schemes, recognizing in his analysis a framework for thinking about why particular policies would likely fail despite their noble intentions. Even critics of capitalism and defenders of more extensive government intervention found themselves engaging Hayekian arguments about the limits of central planning and the importance of price signals for coordinating economic activity.

Conclusion

Friedrich Hayek’s legacy is a unified vision linking economics and political theory: decentralized decision‑making, market prices as spontaneous information processors, and constitutional limits on power together preserve individual freedom and human dignity. He warned that monetary intervention and central planning distort signals, produce malinvestment, and require coercive authority to enforce outcomes—undermining both economic efficiency and liberty—and he rejected “social justice” as a coherent basis for policy because it necessitates discretionary interventions that violate the rule of law.

From this diagnosis Hayek proposed institutional remedies: governments should confine themselves to general, knowable rules that protect property, enforce contracts, and maintain competition; decisions requiring dispersed, local knowledge should be made at decentralized levels; and constitutions should harden safeguards—separation of powers, federalism, limits on particularized legislation, and fiscal constraints—to prevent majoritarian or bureaucratic usurpation of freedom. Whether one accepts all his claims, his emphasis on the limits of knowledge, the evolutionary nature of complex systems, and the primacy of rule‑based liberty remains influential in debates about economic policy and constitutional design.

Selected texts

Friedrich A. Hayek. The Pretense of Knowledge. Nobel Memorial Lecture, December 11,1974.

(…)

To act on the belief that we possess the knowledge and the power which enable us to shape the processes of society entirely to our liking, knowledge which in fact we do not possess, is likely to make us do much harm. In the physical sciences there may be little objection to trying to do the impossible; one might even feel that one ought not to discourage the over-confident because their experiments may after all produce some new insights. But in the social field the erroneous belief that the exercise of some power would have beneficial consequences is likely to lead to a new power to coerce other men being conferred on some authority. Even if such power is not in itself bad, its exercise is likely to impede the functioning of those spontaneous ordering forces by which, without understanding them, man is in fact so largely assisted in the pursuit of his aims. We are only beginning to understand on how subtle a communication system the functioning of an advanced industrial society is based—a communications system which we call the market and which turns out to be a more efficient mechanism for digesting dispersed information than any that man has deliberately designed.

(…)

Friedrich A. Hayek. The Use of Knowledge in Society. The American Economic Review, Volume 35, Issue 4 (Seр., 1945), 519-530.

(…)

The peculiar character of the problem of a rational economic order is determined precisely by the fact that the knowledge of the circumstances of which we must make use never exists in concentrated or integrated form, but solely as the dispersed bits of incomplete and frequently contradictory knowledge which all the separate individuals possess. The economic problem of society is thus not merely a problem of how to allocate “given” resources-if “given” is taken to mean given to a single mind which deliberately solves the problem set by these “data.” It is rather a problem of how to secure the best use of resources known to any of the members of society, for ends whose relative importance only these individuals know. Or, to put it briefly, it is a problem of the utilization of knowledge not given to anyone in its totality.

(…)

We must look at the price system as such a mechanism for communicating information if we want to understand its real function-a function which, of course, it fulfills less perfectly as prices grow more rigid. (Even when quoted prices have become quite rigid, however, the forces which would operate through changes in price still operate to a considerable extent through changes in the other terms of the contract.) The most significant fact about this system is the economy of knowledge with which it operates, or how little the individual participants need to know in order to be able to take the right action. In abbreviated form, by a kind of symbol, only the most essential information is passed on, and passed on only to those concerned. It is more than a metaphor to describe the price system as a kind of machinery for registering change, or a system of telecommunications which enables individual producers to watch merely the movement of a few pointers, as an engineer might watch the hands of a few dials, in order to adjust their activities to changes of which they may never know more than is reflected in the price movement.

(…)

Friedrich A. Hayek. THE FATAL CONCEIT. The Errors of Socialism. Routledge, London, 1988.

The Fatal Conceit

(…)

To the naive mind that can conceive of order only as the product of deliberate arrangement, it may seem absurd that in complex conditions order, and adaptation to the unknown, can be achieved more effectively by decentralising decisions, and that a division of authority will actually extend the possibility of overall order. Yet that decentralisation actually leads to more information being taken into account. This is the main reason for rejecting the requirements of constructivist rationalism. For the same reason, only the alterable division of the power of disposal over particular resources among many individuals actually able to decide on their use – a division obtained through individual freedom and several property – makes the fullest exploitation of dispersed knowledge possible.

Much of the particular information which any individual possesses can be used only to the extent to which he himself can use it in his own decisions. Nobody can communicate to another all that he knows, because much of the information he can make use of he himself will elicit only in the process of making plans for action. Such information will be evoked as he works upon the particular task he has undertaken in the conditions in which he finds himself, such as the relative scarcity of various materials to which he has access. Only thus can the individual find out what to look for, and what helps him to do this in the market is the responses others make to what they find in their own environments. The overall problem is not merely to make use of given knowledge, but to discover as much information as is worth searching for in prevailing conditions.

It is often objected that the institution of property is selfish in that it benefits only those who own some, and that it was indeed invented by some persons whom having acquired some individual possessions, wished for their exclusive benefit to protect these from others. Such notions, which of course underlie Rousseau’s resentment, and his allegation that ourshashackles’ have been imposed by selfish and exploitative interests, fail to take into account that the size of our overall product is so large only because we can, through market exchange of severally owned property, use widely dispersed knowledge of particular facts to allocate severally owned resources. The market is the only known method of providing information enabling individuals to judge comparative advantages of different uses of resources of which they have immediate knowledge and through whose use, whether they so intend or not, they serve the needs of distant unknown individuals. This dispersed knowledge is essentially dispersed, and cannot possibly be gathered together and conveyed to an authority charged with the task of deliberately creating order.

Thus the institution of several property is not selfish, nor was it, nor could it have been, `invented’ to impose the will of property-owners upon the rest. Rather, it is generally beneficial in that it transfers the guidance of production from the hands of a few individuals who, whatever they may pretend, have limited knowledge, to a process, the, extended order, that makes maximum use of the knowledge of all, thereby benefiting those who do not own property nearly as much as those who do.

(…)

RELIGION AND THE GUARDIANS OF TRADITION

(…)

We owe it partly to’ mystical and religious beliefs, and, I believe, particularly to the main monotheistic ones, that beneficial traditions have been preserved and transmitted at least long enough to enable those groups following them to grow, and to have the opportunity to spread by natural or cultural selection. This means that, like it or not, we owe the persistence of certain practices, and the civilisation that resulted from them, in part to support from beliefs which are not true – or verifiable or testable – in the same sense as are scientific statements, and which are certainly not the result of rational argumentation. I sometimes think that it might be appropriate to call at least some of them, at least as a gesture of appreciation, ‘symbolic’ truths , since the did help their adherents to ‘be fruitful and multiply and replenish the earth and subdue it’ (Genesis 1:28). Even those among us, like myself, who are not prepared to accept the anthropomorphic conception of a personal divinity ought to admit that the premature loss of what we regard as nonfactual beliefs would have deprived mankind of a powerful support in the long development of the extended order that we now enjoy, and that even now the loss of these beliefs, whether true or false, creates great difficulties.

In any case, the religious view that morals were determined by processes incomprehensible to us may at any rate be truer (even if not exactly in the way intended) than the rationalist delusion that man, by exercising his intelligence, invented morals that gave him the power to achieve more than he could ever foresee. If we bear these things in mind, we can better understand and appreciate those clerics who are said to have become somewhat sceptical of the validity of some of their teachings and who yet continued to teach them because they feared that a loss of faith would lead to a decline of morals. No doubt they were right; and even an agnostic ought to concede that we owe our morals, and the tradition that has provided not only our civilisation but our very lives, to the acceptance of such scientifically unacceptable factual claims.

The undoubted historical connection between religion and the values that have shaped and furthered our civilisation, such as the family and several property, does not of course mean that there is any intrinsic connection between religion as such and such values. Among the founders of religions over the last two thousand years, many opposed property and the family. But the only religions that have survived are those

which support property and the family. Thus the outlook for communism, which is both anti-property and anti-family (and also anti-religion), is not promising. For it is, I believe, itself a religion which had its time, and which is now declining rapidly. In communist and socialist countries we are watching how the natural selection of religious beliefs disposes of the maladapted.

(…)

I long hesitated whether to insert this personal note here, but ultimately decided to do so because support by a professed agnostic may help religious people more unhesitatingly to pursue those conclusions that we do share. Perhaps what many people mean in speaking of God is just a personification of that tradition of morals or values that keeps their community alive. The source of order that religion ascribes to a human-like divinity – the map or guide that will show a part successfully how to move within the whole – we now learn to see to be not outside the physical world but one of its characteristics, one far too complex for any of its parts possibly to form an image' or picture’ of it. Thus religious prohibitions against idolatry, against the making of such images, are well taken. Yet perhaps most people can conceive of abstract tradition only as a personal Will. If so, will they not be inclined to find this will in `society’ in an age in which more overt supernaturalisms are ruled out as superstitions?

On that question may rest the survival of our civilisation.

Friedrich A. Hayek.. THE INTELLECTUALS AND SOCIALISM. University of Chicago Law Review: Vol. 16: Iss. 3, Article 7, 1949.

(…)

It is not surprising that the real scholar or expert and the practical man of affairs often feel contemptuous about the intellectual, are disinclined to recognise his power, and are resentful when they discover it. Individually they fi nd the intellectuals mostly to be people who understand nothing in particular especially well and whose judgement on matters they themselves understand shows little sign of special wisdom. But it would be a fatal mistake to underestimate their power for this reason. Even though their knowledge may be often superfi cial and their intelligence limited, this does not alter the fact that it is their judgement which mainly determines the views on which society will act in the not too distant future. It is no exaggeration to say that, once the more active part of the intellectuals has been converted to a set of beliefs, the process by which these become generally accepted is almost automatic and irresistible. These intellectuals are the organs which modern society has developed for spreading know ledge and ideas, and it is their convictions and opinions which operate as the sieve through which all new conceptions must pass before they can reach the masses.

(…)

Questions for reflection

1. If Hayek argued that no central authority could gather sufficient information to coordinate a modern economy efficiently, how should contemporary governments approach the regulation of artificial intelligence systems that are themselves attempting to process vast amounts of dispersed information at unprecedented scale? Does AI technology fundamentally change the nature of the knowledge problem, or does it merely create a more sophisticated version of the same coordination challenge?

2. Hayek maintained that complex social institutions like markets, language, and legal systems evolved through spontaneous processes rather than conscious design, yet he himself proposed detailed constitutional reforms and a complete redesign of the monetary system through denationalization. How can this apparent contradiction between his belief in spontaneous order and his proposals for deliberate institutional redesign be reconciled?

3. Hayek’s Austrian business cycle theory attributes economic booms and busts to government manipulation of money and interest rates, yet modern central banks argue such interventions prevent catastrophic depressions. In the context of the 2008 financial crisis and subsequent monetary interventions, was Hayek correct that central bank manipulation causes more harm than good, or do contemporary circumstances require active monetary management?

4. The United States and other developed nations have recently pursued industrial policy to strengthen semiconductor production, renewable energy manufacturing, and other strategic sectors. How would Hayek’s critique of central planning apply to these modern industrial policies, and what would be his alternative approach to ensuring robust supply chains without government direction?

5. Hayek emphasized the importance of decentralized decision-making based on local knowledge, yet many cities maintain restrictive zoning laws and building regulations that prevent housing construction. Are these regulations examples of Hayekian “planning” that should be eliminated in favor of market-driven development, or might there be legitimate reasons for communities to constrain growth through local governance structures?

6. In what ways does Hayek argue that pursuing “social justice” through government intervention undermines the rule of law and leads to arbitrary power?

7. Hayek argued that legitimate government must operate through general, knowable rules rather than discretionary commands. How does this principle apply to modern regulatory agencies that exercise significant discretion in interpreting ambiguous statutes, and should contemporary democracies constrain administrative agency power more strictly to align with Hayekian rule-of-law principles?

8. Hayek visited Chile during General Augusto Pinochet’s military dictatorship and suggested that temporary authoritarian rule might be justified if it clearly moved toward limited democracy. Given his lifetime of arguments about the dangers of concentrated power, how can his willingness to accept dictatorship in the name of economic freedom be defended, and does this position undermine his broader philosophy?

9. Hayek proposed in 1976 that private institutions should issue competing currencies to replace government monetary monopolies, a vision that seems partially realized through Bitcoin and stablecoins. Do cryptocurrencies and blockchain-based money systems vindicate Hayek’s vision of denationalized money, or do their extreme price volatility and practical limitations suggest that his proposal was theoretically sound but practically unfeasible without technological innovation that he could not have anticipated?

10. In the context of rising concerns about big tech companies and data privacy, how might Hayek’s emphasis on competition and spontaneous order inform proposals for regulating social media platforms?

11. How does Hayek’s advocacy for decentralization and local governance relate to current debates over federal versus state authority in handling issues like education or healthcare?