Introduction

Robert Nozick (1938–2002) was a prominent American philosopher renowned for his pivotal contributions to political philosophy, metaphysics, and epistemology. He held a teaching position at Harvard University and became a significant voice in libertarian thought, though he later distanced himself from strict interpretations of libertarianism.

Figure 34: Robert Nozick

Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Robert_Nozick_1977_Libertarian_Review_cover.jpg

His philosophical approach melded analytic philosophy with influences from Austrian economics (notably Friedrich Hayek) and Lockean natural rights theory. He challenged dominant perspectives on justice, ethics, and the state’s role, advocating for a rights-based, minimalist approach while critiquing utilitarianism, egalitarianism, and hedonism.

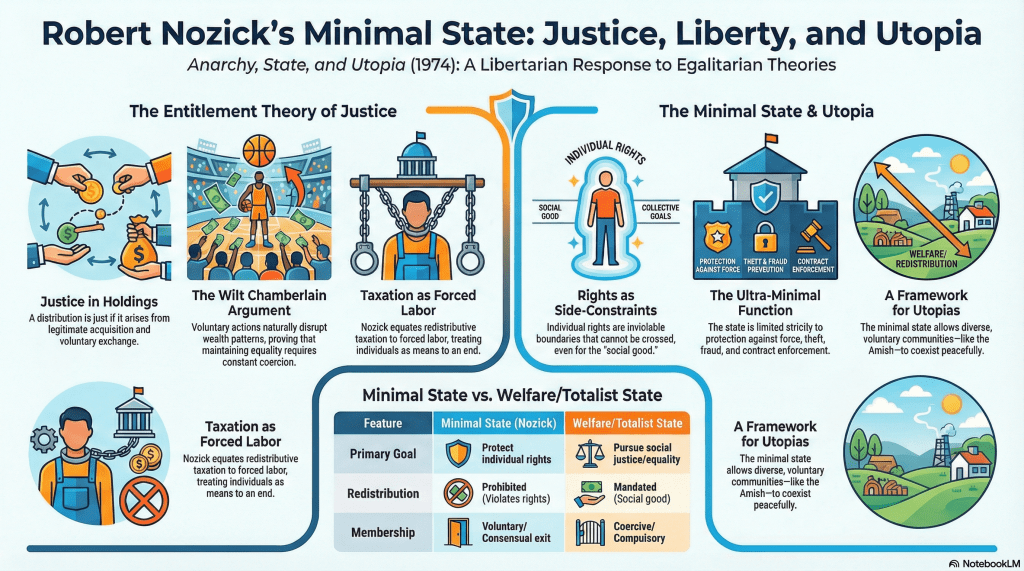

Anarchy, State, and Utopia

His most influential work, Anarchy, State, and Utopia (1974), is a foundational text in libertarian political, serving as a direct response to John Rawls’ egalitarian theory of justice. Divided into three parts, the book defends a minimal state that protects individual rights without engaging in redistribution or paternalism. Nozick begins from a Lockean state of nature, emphasizing inviolable individual rights as side-constraints that cannot be overridden for collective goals. Central to his argument is the “entitlement theory” of justice, which posits that a distribution is just if it arises from just acquisitions and voluntary transfers, rejecting patterned theories like equality or utilitarianism that require constant interference.

In the first part, “Anarchy,” Nozick critiques anarcho-capitalism by demonstrating how a minimal state could emerge legitimately through an invisible-hand process. Individuals in a state of nature form protective associations for security; competition leads to a dominant agency that functions as a de facto state with a monopoly on force, without violating rights. This ultra-minimal state enforces contracts and protects against aggression but does not redistribute resources. Nozick argues that prohibiting independent enforcement would be necessary to prevent cycles of retaliation, thus justifying the transition to a minimal state.

| Libertarians: the Chirping Sectaries Russell Kirk (1918–1994) was an American political philosopher, considered one of the most important figures in the American conservatism In the essay “Libertarians: the Chirping Sectaries“, Russell Kirk traces the intellectual roots of modern libertarianism to the “flimsy” and “farcical” arguments of John Stuart Mill, particularly his “one very simple principle” that society should only interfere with individual liberty for self-protection. This abstract principle is criticized for ignoring the complexity of human behavior and the historical reality that most significant human movements have been achieved through force rather than free discussion. Ultimately, Kirk views the libertarian obsession with absolute personal freedom as a “metaphysical madness” that lacks an understanding of the inherent limitations of human nature. According to Russell Kirk, while conservatives and libertarians both oppose collectivism, the totalist state, and bureaucracy, they share virtually nothing else. But, the divide between the two groups is rooted in fundamentally different views of human nature and moral order. Conservatives believe that human nature is irremediably flawed and that social order must be established before liberty or justice can be secured. In contrast, libertarians generally believe in the inherent goodness of humanity and prioritize an abstract, indefinable “liberty” at the expense of the very order that protects freedom. Furthermore, while conservatives see society as a “community of souls” bound by love and friendship across generations, libertarians view social ties through the lens of self-interest and “the nexus of cash payment”. This leads to a conflict regarding the state; conservatives view it as a necessary means of restraint ordained by God, while libertarians view the state as the great oppressor. Because of these deep-seated differences, Kirk asserts that a political alliance is inconceivable, likening such a coalition to a “union of ice and fire”. Practical issues further widen the gap; for instance, Kirk notes that the Libertarian Party’s historical support for abortion is viewed by conservatives as a “despicable evil”. Kirk characterizes libertarians as a “chirping sect” of ineffectual ideologues who delight in eccentricity and defy traditional authority. He concludes that genuine conservatives must distance themselves from this “doctrinaire selfishness,” predicting that while some intelligent individuals may eventually migrate to the conservative camp, the libertarian movement will remain a diminishing minority that denies the premises of the American social order. (https://www.mikechurch.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/Libertarians_chirping_sectaries_Russell_Kirk.pdf) |

The second part, “State,” argues against expanding the state beyond minimal functions. Nozick uses thought experiments like the Wilt Chamberlain argument to show that voluntary transactions inevitably disrupt any patterned distribution, requiring coercive interventions that infringe on liberty. He equates redistributive taxation to forced labor, viewing it as treating individuals as means rather than ends. Critiquing Rawls, Nozick rejects the idea of hypothetical consent behind a veil of ignorance, insisting that rights are absolute and that the state has no moral authority to pursue social justice through wealth transfer or regulation.

| The Wilt Chamberlain argument Robert Nozick’s Wilt Chamberlain argument is a thought experiment intended to challenge patterned or end-state principles of distributive justice (those that require resources be distributed according to a specific pattern, like equality or distribution according to moral merit). Nozick asks us to imagine a society that has a just distribution of wealth according to some pattern. Suppose people freely choose to pay a small fee to watch Wilt Chamberlain play basketball, and by voluntary exchange Chamberlain accumulates a large sum. This new distribution departs from the original patterned distribution, yet arose from free, consensual transfers. Nozick argues that if the initial distribution was just and all subsequent transfers were voluntary, then the resulting unequal distribution must also be just, showing that enforcing a pattern would require continuous interference with people’s voluntary exchanges. From this Nozick concludes that redistributive actions to preserve any chosen pattern would violate individual rights by treating people as means to an end: to maintain the pattern, the state would need to seize holdings or restrict transfers, thereby infringing on individuals’ liberty. He therefore defends the entitlement theory: justice consists in just acquisition, transfer, and rectification of past injustices. If holdings arise from these legitimate processes, then any resulting inequalities are permissible, and attempts to enforce a patterned distribution are unjust because they override individuals’ rights to use their holdings as they choose. |

In the third part, “Utopia,” Nozick presents the minimal state as a “framework for utopias,” allowing diverse communities to flourish voluntarily within its protective bounds. Individuals can form or join experimental societies—socialist, capitalist, or otherwise—as long as participation is consensual and exit is free. This meta-utopia promotes pluralism and personal choice, suggesting that the minimal state, while not utopian itself, enables the realization of varied conceptions of the good life. Overall, the book champions individualism, challenging the welfare state and inspiring ongoing debates on liberty versus equality.

| The US framework for utopias The existence of a limited federal government, states with comprehensive legislative capacity, and the possibility of creating intentional communities regulated by their own rules creates the possibility of concrete freedom, to choose one’s way of life, more or less collectivist, more or less religious, etc., bringing together enough people to create a community guided by the utopia of its members. In this sense, in the US, despite its government not being minimalist, numerous intentional communities exemplify the possibility of utopias, to which Nozick refers, operating within legal limits — buying land, forming associations and self-governing — while relying on the protection of the State for security and property rights. These communities validate Nozick’s argument by demonstrating how pluralism flourishes under a neutral structure, attracting members who choose to participate and allowing them to leave without coercion. One prominent example is Amish communities, such as those in Pennsylvania and Ohio, where thousands live in agrarian, religious enclaves emphasizing simplicity, pacifism, and separation from modern technology. These groups voluntarily adhere to strict communal rules (e.g., no electricity, plain dress), with members joining through baptism as adults and able to leave via “rumspringa” or excommunication processes. The US state supports this by granting exemptions (e.g., from Social Security) and protecting their property, illustrating Nozick’s point that diverse “utopias” can coexist without state interference in internal affairs, as long as rights are respected. |

Impact

Anarchy, State, and Utopia revitalized academic libertarianism and influenced thinkers like Milton Friedman. It sparked debates on inequality, rights, and the scope of government, particularly concerning welfare states.

Anarchy, State, and Utopia had a profound immediate impact on political philosophy, emerging as a direct counterpoint to John Rawls’ A Theory of Justice and revitalizing libertarian thought in academic circles. The book’s defense of a minimal state, entitlement theory of justice, and critiques of redistributive policies challenged prevailing egalitarian and utilitarian frameworks, influencing generations of philosophers, economists, and legal scholars. It won the National Book Award in 1975 and is frequently cited as one of the most influential works of 20th-century political philosophy, sparking extensive debates on individual rights versus collective welfare. By emphasizing inviolable side-constraints on actions and using thought experiments like the Wilt Chamberlain argument, Nozick shifted discussions toward process-oriented justice, inspiring libertarian movements and critiques of expansive government.

Fifty years on, its legacy endures as a cornerstone of libertarian ideology, with ongoing reflections highlighting its role in defending classical liberalism against state overreach. In contemporary contexts, it continues to inform debates on inequality, property rights, and utopian pluralism, remaining a frequently referenced text in philosophical and policy discussions.

Selected texts

ROBERT NOZICK. ANARCHY, STATE, AND UTOPIA.

Preface

INDIVIDUALS have rights, and there are things no person or group may do to them (without violating their rights). So strong and far-reaching are these rights that they raise the question of what, if anything, the state and its officials may do. How much room do individual rights leave for the state? The nature of the state, its legitimate functions and its justifications, if any, is the central concern of this book; a wide and diverse variety of topics intertwine in the course of our investigation.

Our main conclusions about the state are that a minimal state, limited to the narrow functions of protection against force, theft, fraud, enforcement of contracts, and so on, is justified; that any more extensive state will violate persons’ rights not to be forced to do certain things, and is unjustified; and that the minimal state is inspiring as well as right. Two noteworthy implications are that the state may not use its coercive apparatus for the purpose of getting some citizens to aid others, or in order to prohibit activities to people for their own good or protection.

(…)

PART I. State-of-Nature Theory, or How to Back into a State without Really Trying

CHAPTER 1. Why State-of-Nature Theory?

IF the state did not exist would it be necessary to invent it? Would one be needed, and would it have to be invented? These questions arise for political philosophy and for a theory explaining political phenomena and are answered by investigating the “state of nature,” to use the terminology of traditional political theory. The justification for resuscitating this archaic notion would have to be the fruitfulness, interest, and far-reaching implications of the theory that results. For the (less trusting) readers who desire some assurance in advance, this chapter discusses reasons why it is important to pursue state-of-nature theory, reasons for thinking that theory would be a fruitful one. These reasons necessarily are somewhat abstract and metatheoretical. The best reason is the developed theory itself.

The fundamental question of political philosophy, one that precedes questions about how the state should be organized, is whether there should be any state at all. Why not have anarchy? Since anarchist theory, if tenable, undercuts the whole subject of political philosophy, it is appropriate to begin political philosophy with an examination of its major theoretical alternative. Those who consider anarchism not an unattractive doctrine will think it possible that political philosophy ends here as well. Others impatiently will await what is to come afterwards. Yet, as we shall see, archists and anarchists alike, those who spring gingerly from the starting point as well as those reluctantly argued away from it, can agree that beginning the subject of political philosophy with state of-nature theory has an explanatory purpose. (Such a purpose is absent when epistemology is begun with an attempt to refute the skeptic.)

(…)

Since considerations both of political philosophy and of explanatory political theory converge upon Locke’s state of nature, we shall begin with that. More accurately, we shall begin with individuals in something sufficiently similar to Locke’s state of nature so that many of the otherwise important differences may be ig

nored here. Only when some divergence between our conception and Locke’s is relevant to political philosophy, to our argument about the state, will it be mentioned. The completely accurate statement of the moral background, including the precise state ment of the moral theory and its underlying basis, would require a full-scale presentation and is a task for another time. (A lifetime?) That task is so crucial, the gap left without its accomplishment so yawning, that it is only a minor comfort to note that we here are following the respectable tradition of Locke, who does not provide anything remotely resembling a satisfactory explanation of the status and basis of the law of nature in his Second Treatise.

(…)

CHAPTER 3. Moral Constraints and the State

(…)

Political philosophy is concerned only with certain ways that persons may not use others; primarily, physically aggressing against them. A specific side constraint upon action toward others expresses the fact that others may not be used in the specific ways the side constraint excludes. Side constraints express the in violability of others, in the ways they specify. These modes of in violability are expressed by the following injunction: “Don’t use people in specified ways.” An end-state view, on the other hand, would express the view that people are ends and not merely means (if it chooses to express this view at all), by a different injunction: “Minimize the use in specified ways of persons as means.” Following this precept itself may involve using someone as a means in one of the ways specified. Had Kant held this view, he would have given the second formula of the categorical imperative as, “So act as to minimize the use of humanity simply as a means,” rather than the one he actually used: “Act in such a way that you always treat humanity, whether in your own person or in the person of any other, never simply as a means, but always at the same time as an end.”

Side constraints express the inviolability of other persons. But why may not one violate persons for the greater social good? Individually, we each sometimes choose to undergo some pain or sacrifice for a greater benefit or to avoid a greater harm: we go to the dentist to avoid worse suffering later; we do some unpleasant work for its results; some persons diet to improve their health or looks; some save money to support themselves when they are older. In each case, some cost is borne for the sake of the greater overall

good. Why not, similarly, hold that some persons have to bear some costs that benefit other persons more, for the sake of the overall social good? But there is no social entity with a good that undergoes some sacrifice for its own good. There are only individual people, different individual people, with their own individual lives. Using one of these people for the benefit of others, uses him and benefits the others. Nothing more. What happens is that something is done to him for the sake of others. Talk of an overall social good covers this up. (Intentionally?) To use a person in this way does not sufficiently respect and take account of the fact that he is a separate person, that his is the only life he has. He does not get some overbalancing good from his sacrifice, and no one is entitled to force this upon him —least of all a state or government that claims his allegiance (as other individuals do not) and that therefore scrupulously must be neutral between its citizens.

LIBERTARIAN CONSTRAINTS

The moral side constraints upon what we may do, I claim, reflect the fact of our separate existences. They reflect the fact that no moral balancing act can take place among us; there is no moral outweighing of one of our lives by others so as to lead to a greater overall social good. There is no justified sacrifice of some of us for others. This root idea, namely, that there are different individuals with separate lives and so no one may be sacrificed for others, underlies the existence of moral side constraints, but it also, I believe, leads to a libertarian side constraint that prohibits aggression against another.

(…)

A nonaggression principle is often held to be an appropriate principle to govern relations among nations. What difference is there supposed to be between sovereign individuals and sovereign nations that makes aggression permissible among individuals? Why may individuals jointly, through their government, do to someone what no nation may do to another? If anything, there is a stronger case for nonaggression among individuals; unlike nations, they do not contain as parts individuals that others legitimately might intervene to protect or defend.

(…)

Questions for reflection

1. How does Nozick’s entitlement theory challenge contemporary understandings of distributive justice, especially in light of ongoing debates about wealth inequality?

2. In what ways does the Wilt Chamberlain argument illustrate the potential conflicts between individual freedom and the pursuit of equality in modern welfare states?

3. In what ways does Wilt Chamberlain’s argument illustrate the fact that violence (revolution) for the construction of socialist states is not sufficient for their maintenance, but that permanent mechanisms of violence are necessary to restrict individual freedom?

4. How might Nozick’s concept of a “minimal state” apply to current discussions about the role of government in areas like healthcare and education?

5. Nozick equates taxation for redistribution with forced labor. If it’s not forced labor, what would be the justification for taxation?

6. In Anarchy, State, and Utopia, why does Nozick argue that individual rights act as side-constraints that cannot be violated for the greater good, and how does this perspective critique government responses to public health crises like the COVID-19 pandemic.

7. Does the possibility of each individual living, or not, in a utopian socialist community built in a country with a minimalist government satisfy the demands of socialists, or, if the real demand of socialists is for power and control, are they not satisfied with this possibility and will they continue to seek a state that subjects everyone to their utopia?

Leave a comment