Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov (1870–1924) was a Russian revolutionary, Marxist theorist, and the primary architect of the Bolshevik Revolution that established Soviet rule in Russia.

Figure 26. Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov

Source. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Vladimir_Lenin.jpg

Born into a middle-class family in Simbirsk (now Ulyanovsk), Lenin was radicalized after his brother’s execution for plotting against Tsar Alexander III in 1887. He studied law but was expelled from university for participating in student protests. Lenin spent years in exile, developing his interpretation of Marxism, which emphasized the need for a vanguard party of professional revolutionaries to lead the proletariat in overthrowing capitalism.

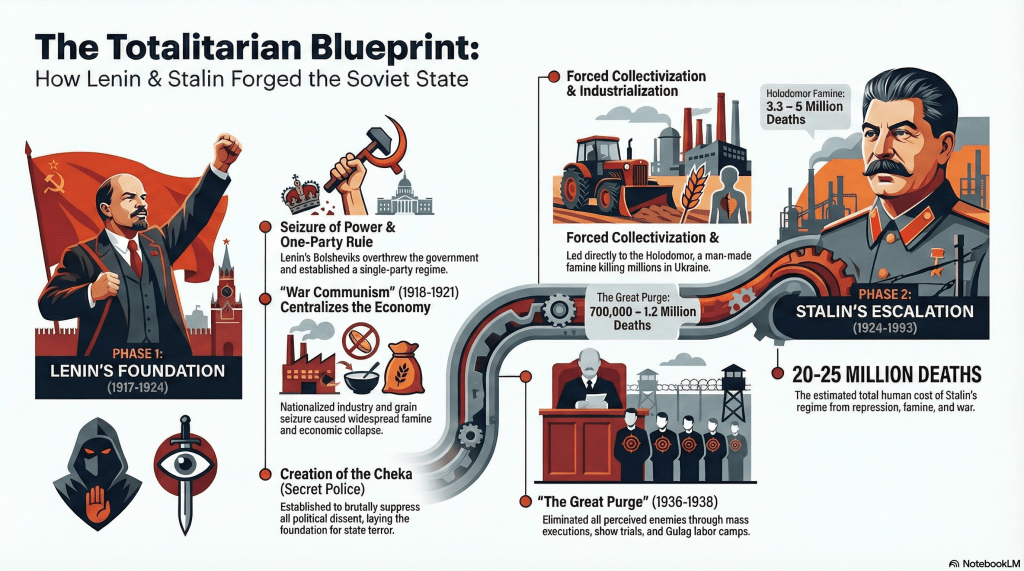

Lenin’s key policies shaped the early Soviet Union. In 1917, he returned from exile amid World War I chaos and led the October Revolution, overthrowing the Provisional Government.

As head of the new Bolshevik government, he implemented “War Communism” (1918–1921), which involved nationalizing industry, requisitioning grain from peasants, and centralizing economic control to support the Red Army during the Russian Civil War.

This policy caused widespread famine and economic collapse, killing millions.

In response, Lenin introduced the New Economic Policy (NEP) in 1921, allowing limited private enterprise and market mechanisms to revive the economy while maintaining state control over key sectors.

He also established the Cheka (secret police) to suppress dissent, laying foundations for authoritarian control.

Lenin suffered strokes starting in 1922 and died in 1924, leaving a power vacuum.

Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili, 1878–1953) was a Georgian revolutionary who rose to become the Soviet Union’s dictator from the mid-1920s until his death.

Figure 27. Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin

Source. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Joseph_Stalin_in_1932_(4)_(cropped)(2).jpg

From a poor family in Gori, Georgia, Stalin trained as a priest but was expelled from seminary for revolutionary activities. He joined the Bolsheviks in the early 1900s, organizing strikes, robberies, and propaganda under Lenin, who valued his ruthlessness.

After the 1917 Revolution, Stalin served as Commissar for Nationalities and later General Secretary of the Communist Party (1922), a position he used to build a loyal network.

Following Lenin’s death, Stalin outmaneuvered rivals like Leon Trotsky through alliances and purges, consolidating power by 1927–1928.

His rule transformed the USSR into an industrial powerhouse via the Five-Year Plans (starting 1928), emphasizing rapid industrialization, collectivization of agriculture, and state control.

Collectivization forcibly consolidated farms, leading to the Holodomor famine (1932–1933) in Ukraine, killing millions.

| The Holodomor The Holodomor, a man-made famine in Soviet Ukraine from 1932–1933 engineered under Joseph Stalin’s policies, resulted in massive loss of life. Scholarly estimates of the death toll vary due to challenges in accessing historical data, discrepancies in Soviet records, and debates over methodologies (e.g., whether to include direct starvation deaths only, related diseases, birth deficits, or migration effects). Early accounts and some political statements cited higher figures of 7–10 million, but more recent demographic studies based on declassified archives generally converge on lower ranges. Most experts estimate 3.3–5 million deaths in Ukraine specifically, with some detailed demographic analyses pinpointing around 3.9 million direct excess deaths (e.g., from starvation and famine-related causes). The Holodomor was part of a wider Soviet famine (1930–1933) affecting regions like Kazakhstan and Russia, with total deaths across the USSR estimated at 5.5–8.7 million. The Holodomor is widely recognized as a genocide by Ukraine and many countries, though Russia disputes this, of course. |

Stalin’s Great Purge (1936–1938) eliminated perceived enemies through show trials, executions, and Gulag labor camps, resulting in 700,000–1.2 million deaths.

He fostered a cult of personality, portraying himself as an infallible leader.

During World War II, Stalin allied with the West against Nazi Germany, but postwar he expanded Soviet influence in Eastern Europe.

His regime caused 20–25 million deaths from repression, famine, and war.

Instead of paradise, hell on earth

The USSR’s evolution into a totalitarian state began under Lenin but intensified under Stalin.

The trajectory of the USSR shows how Marxism’s promise of equality disintegrates into “unfreedom and inequality,” mirroring fascism as a post-communist illusion.

In short, the steps of this transformation in the former USSR were:

- Under Lenin, the Bolsheviks seized power in 1917 amid economic chaos and civil war, establishing a one-party regime.

- War Communism centralized the economy, banned opposition parties, and used the Cheka to execute or imprison dissidents (e.g., the Red Terror, which killed tens of thousands).

- The Kronstadt Rebellion of 1921, led by sailors (former Bolshevik supporters), was brutally suppressed, signaling intolerance of internal criticism.

- Lenin’s NEP relaxed some controls, but the state maintained dominance over politics and the media.

- Stalin accelerated totalitarianism after 1924, abandoning the NEP in favor of complete state planning.

- He centralized the economy, purged rivals (for example, exiling Trotsky in 1929), and used propaganda, the secret police (NKVD), and surveillance to control society.

- By the 1930s, the USSR featured total state ownership, a one-man dictatorship, indoctrination through education and art, and mass terror.

| Marxism is Fascism and National Socialism Stalin’s USSR was functionally fascist—”Red Fascism”—due to shared totalitarian traits like leader cults, state control, suppression of individualism, and even antisemitism (Stalin’s late purges targeted “cosmopolitan” Jews). Both systems rejected liberalism, used violence for ideological ends, and centralized power. Friedrich August von Hayek (in his work The Road to Serfdom, 1944) explains how socialist is some kind of fascism as follows: “(…) Similarly, a Britsh writer F. A. Voigt, after many years of close observations of developments in Europe as a foreign correspondent, concludes that “Marxism led to Fascism and National Socialism because, in all essencials, it is Fascism and National Socialism.” And Dr. Walter Lippmann has arrived at the conviction that “the generation to which we belong is now learning by experience what happens when men retreat from freedom to a coercive organize of their affairs. Though they promise themselves a more abundant life, they must in practice renounce it; as the organization direction increases, the variety of ends must give way to uniformity. That is the nemesis of the planned society and the authoritarian principle in human affairs.” Many more similar statements from people in a position to judge might be selected from publications of recent years, particularly from those by men as citizens of now totalitarian countries have lived through the transformation and have been forced by their experiente to revise cherished beliefs. We shall quote as one more example a German writer who express the same conclusion perhaps more justly than those already quoted. “The complete collapse of the belief in the attainability of freedom and equality through Marxism”, writes Peter Drucker, “has forced Russia to travel the same road toward a totalitarian, purely negative, non-economic society of unfreedom and inequality which German has being following . Not that communism and fascism are essentially the same. Fascism is the stage reached after communism has proven an illusion in Stalinist Russia as in pre-Hitler Germany.” No less significant is the intellectual history of many Nazi and Fascist leaders. Everyone who has watched the growth of these movements in Italy or Germany has been stuck by the number of leading men, from Mussolini downward (and not excluding Laval and Quisling), who began as socialists and ended as Fascists or Nazis. (…) Lest this be doubted by people mislead by official propaganda from either side, let me quote one more statement from an authority that ought not to be suspected. In an article under the significant title “The Rediscovery of Liberalism,” Professor Eduard Heimann, one of the leaders of German religious socialism, writes: Hitlerism proclaims itself both to be true democracy and true socialism, and the terrible truth is that there is a grain of truth for such claims — an infinitesimal grain, to be sure, but at any rate enough to serve as a basis for such fantastic distortions. Hitlerism even goes so far as to claim the role of protector of Christianity, and the terrible truth is that even this gross misinterpretation is able to make an impression. But one fact stands out with all the fog: Hitler never claimed to represent true liberalism. Liberalism has the distinction of being the doctrine most hated by Hitler.” It should be added that this hatred had little occasion to show itself in practice merely because, by the time Hitler came to power, liberalism was, for all intents and purposes, dead in Germany. And it was socialism that had killed it. While to many who had watched the transition from socialism to fascism at close quarters the connection between the two systems has became increasingly obvious, in the democracies the majority of people still believe that socialism and freedom can be combined.” Despite Hayek’s understanding, academic consensus distinguishes them: fascism (e.g., Mussolini’s Italy, Hitler’s Germany) was ultranationalist, corporatist, and often race-based, seeking the “rebirth” of a mythical past, while Soviet communism was internationalist, class-focused, and oriented toward a future utopia, hence a classification as radical statist for both. |

The USSR self-identified as antifascist, especially after WWII victories against Nazis in World War II..

Key Quotes from Vladimir Lenin

- “Truth is the most precious thing. That’s why we should ration it.“

- “Crime is a product of social excess.“

- “One man with a gun can control 100 without one.”

| The Importance of a Free Press Hannah Arendt (1906 – 1975) was a German and American philosopher. In a 1973 interview, she explained why one of the first measures of a totalitarian government or any other dictatorship is the suppression of freedom of the press: “The moment we no longer have a free press, anything can happen. What makes it possible for a totalitarian or any other dictatorship to rule is that people are not informed; how can you have an opinion if you are not informed? If everybody always lies to you, the consequence is not that you believe the lies, but rather that nobody believes anything any longer. This is because lies, by their very nature, have to be changed, and a lying government has constantly to rewrite its own history. On the receiving end you get not only one lie—a lie which you could go on for the rest of your days—but you get a great number of lies, depending on how the political wind blows. And a people that no longer can believe anything cannot make up its mind. It is deprived not only of its capacity to act but also of its capacity to think and to judge. And with such a people you can then do what you please.“ |

Key Quotes from Joseph Stalin

- “A single death is a tragedy; a million deaths is a statistic.”

- “Death is the solution to all problems. No man – no problem.”

- “Those who vote decide nothing. Those who count the vote decide everything.“

- “Ideas are more powerful than guns. We would not let our enemies have guns, why should we let them have ideas.“

- “Education is a weapon, whose effect depends on who holds it in his hands and at whom it is aimed.”

- “Gratitude is a sickness suffered by dogs.“

- “Print is the sharpest and the strongest weapon of our party.”

- “Mankind is divided into rich and poor, into property owners and exploited; and to abstract oneself from this fundamental division; and from the antagonism between poor and rich means abstracting oneself from fundamental facts.“

- “I trust no one, not even myself.“

- “The people who cast the votes don’t decide an election, the people who count the votes do.”

| The Brazilian electronic voting system The Brazilian electronic voting system, in place since 1996 and fully implemented by 2000, relies entirely on direct-recording electronic (DRE) machines that record votes digitally without producing a voter-verifiable paper trail, rendering a public count of individual votes impossible. This setup means that once votes are cast, they are stored in the machine’s memory and aggregated into bulletins printed at polling stations, but there is no physical ballot for citizens, political parties, or independent observers to manually tally or recount. This inadequacy shifts decisive power from voters to the “counters”—in this case, the electoral authorities at the Superior Electoral Court (TSE) and the proprietary software governing the machines—creating an opaque process where results must be taken on faith rather than verified publicly. Critics argue that without a mechanism for broad scrutiny, the system undermines democratic integrity, as even basic audits are limited to digital records that can be manipulated without detection, fostering suspicions of fraud especially in closely contested elections. The TSE’s resistance to adopting a voter-verified paper audit trail (VVPAT), despite legislative pushes and pilot programs that were dismissed due to cited issues like printer malfunctions and secrecy risks, leaves no independent means for voters to confirm their choices or for society to challenge outcomes. This “black box” nature, combined with restricted source code access and no comprehensive third-party certifications, erodes public trust and invites allegations of systemic bias, as seen in post-election challenges where no recounts were possible, highlighting how the lack of a public count perpetuates reliance on institutional assurances over tangible proof. |

Two Lessons

For radical leftists, the development of projects and plans for socialism is utopian; according to Marx, what matters is the seizure of power. With the seizure of power, what history teaches is that the natural evolution of radical leftism is, in practice, a totalitarian (radical statist) state, which closely resembles the fascism that leftists so strenuously claim to combat.

Given the various attempts to establish communism around the world, all resulting in totalitarian states, the illusion that today’s radical leftists desire paradise on earth for workers is no longer valid; it is merely a project to seize power. And to achieve this, based on the lessons learned from Machiavelli, radical leftists are willing to say and do anything.

Questions for reflection

1. How did the centralization of economic planning under Lenin and Stalin exemplify radical statism, and what were the human costs of policies like collectivization in the USSR?

2. In what ways did the USSR’s transition from Lenin’s New Economic Policy to Stalin’s Five-Year Plans demonstrate the escalation of state control over individual freedoms?

3. Reflecting on Hayek’s argument, how might the ideological roots of Marxism in the USSR have paved the way for totalitarian practices that mirrored aspects of fascism?

4. What role did propaganda and the cult of personality play in sustaining radical statism in the USSR, and how does this compare to modern authoritarian regimes? What is the role of propaganda and the cult of personality in countries like Venezuela (Hugo Chavez and Maduro) and Brazil (Lula da Silva)?

5. How did the suppression of dissent through institutions like the Cheka and NKVD reflect the inherent dangers of unchecked state power in the Soviet system? What about the suppression of dissent in countries like Venezuela and Brazil?

6. In contemporary Russia under Putin, how do elements of state control over media and economy echo the radical statism of the USSR era? Are other countries doing the same?

7. How do contemporary Russian laws against “fake news” relate to Soviet strategies of controlling historical narrative? Are other countries doing the same?

8. How do Putin’s tactics for concentrating political power echo Stalinist methods of gradually eliminating opposition? Are other countries doing the same?

9. What lessons from the USSR’s Gulag system can inform current discussions on surveillance states and political imprisonment in countries like China or North Korea?

10. How might the failure of Soviet central planning influence today’s debates on government intervention in economies, such as in response to climate change or inequality?

Leave a comment