Introduction

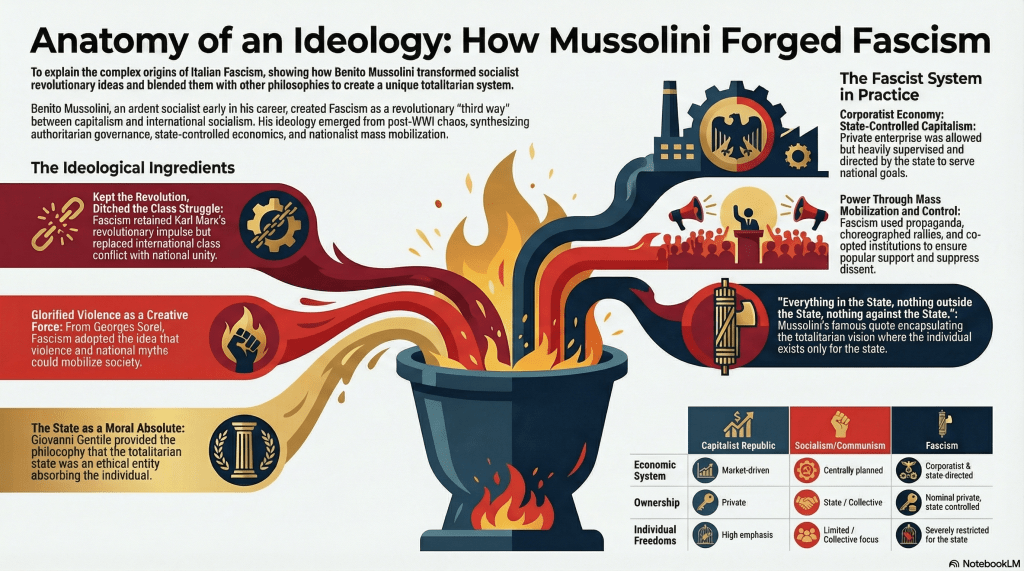

Benito Mussolini (1883-1945), who began his political career as an ardent socialist, created a revolutionary movement that combined ultranationalist rhetoric with state-directed economic control. The fascist ideology emerged from post-World War I Italy’s social chaos, and implemented in Italy from 1922 to 1943, rejected both liberal (capitalistic) democracy and traditional (international) socialism, and represents a “third way” between then, with a synthesis of authoritarian governance, corporate economic organization, market control and mass mobilization techniques that would profoundly influence the trajectory of modern European politics.

Figure 28. Benito Mussolini.

Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Mussolini_mezzobusto.jpg

Main Philosophical Influences

Benito Mussolini’s fascism was not born in isolation but emerged from a confluence of personal experiences, philosophical ideas, political ideologies, and historical circumstances in early 20th-century Italy. Drawing from his socialist roots and the chaos following World War I, Mussolini synthesized diverse influences into a totalitarian ideology emphasizing anti-liberalism, nationalism, action, will, and state absolutism, often rejecting rationalism and individualism. Between them:

- Karl Marx: Mussolini’s fascism represents a complex transformation of Marxist ideas rather than a simple rejection. It retained Marx’s revolutionary impulse, critique of liberalism, and focus on economic organization while rejecting internationalism, class struggle, and economic determinism. The resulting ideology positioned the nation, rather than class, as the fundamental unit of society and sought to resolve class conflict through state-mediated corporatism rather than through proletarian revolution. This transformation helps explain why both fascism and communism developed as totalitarian systems despite their apparent ideological opposition – they shared certain intellectual roots and revolutionary approaches to politics, even as they directed them toward different ends.

- Georges Sorel: Mussolini admired Sorel’s revolutionary syndicalism and ideas on violence as a creative force, including the use of myths (like reviving the Roman Empire) to mobilize masses. This influenced fascism’s anti-intellectual emphasis on action and struggle over theory.

- Niccolò Machiavelli: Mussolini praised The Prince as a guide for statesmen, adopting its pragmatism, use of force, deception, and coercion to maintain power, aligning with fascism’s opportunistic and authoritarian tactics.

- Friedrich Nietzsche: Elements like the “will to power,” glorification of war, and critique of egalitarian democracy resonated with fascism’s elitism and vitality-through-conflict ethos, though Mussolini adapted them selectively.

- Giovanni Gentile: Known as the “philosopher of fascism,” Gentile’s actual idealism—rooted in Hegelian dialectics, Platonic ethics, and Italian thinkers like Benedetto Croce and Giambattista Vico—provided fascism’s intellectual foundation. He viewed the state as an ethical, organic entity that absorbs individuals into a higher unity, justifying totalitarianism as a moral imperative.

| Lessons from Machiavelli On her thesis “Origins of Fascism”, submitted for the Degree of Master of Arts, Evangeline Kodric wrote: “As far as Fascism is concerned, Rocco was correct in saying that “Machiavelli was not only a great political authority; he taught the mastery of energy and will. Fascism learns from him not only its doctrines but its action as well”. And what did Fascism learn? That the end justifies the means; that the end of the state is power, unrelated to morals; that hypocrisy, deceit, religion are tools to further the power of the state; that practical, effective methods for expanding the power of the state ‘are increase of population, formation of fortunate alliances, the maintenance of a national army rather than mercenary troops, regulation of economic activity, the use of dictatorial authority, dash, boldness’.” |

Mussolini’s Political Evolution and Ideological Transformation

Born into a socialist family, with a father who “was an ardent socialist who worked part-time as a journalist for leftist publications, established a committed member of the Italian Socialist Party before World War I. This socialist foundation would prove crucial to understanding his later fascist ideology, as it provided him with organizational skills, rhetorical techniques, and an understanding of mass politics that he would later adapt to serve nationalist rather than internationalist goals.

The pivotal transformation in Mussolini’s political orientation occurred during World War I, when he became “a proponent for the war effort”. This shift marked the beginning of his movement away from orthodox socialism toward what would eventually become fascism. This transformation was not merely opportunistic but reflected a genuine ideological evolution that saw Mussolini rejecting the internationalist aspects of socialism while retaining its revolutionary methodology, mass mobilization techniques and strong aversion of free market economies.

| The Socialist Origins of Fascism Luiz Gonçalves Cavalcante Aguiar da Silva (in “The Socialist Origins of Fascism: From Proletarian Internationalism to Mass Nationalism.” Master’s thesis presented to the Graduate Program in History at the Federal University of the State of Rio de Janeiro, 2019) shows how fascism was not a reaction to socialism or a post-World War I counterrevolutionary [socialist] movement—a thesis defended by radical leftists—but a complex phenomenon, with roots formed before the conflict, influenced by Marxism and Georges Sorel’s syndicalism, among others, and a response to the internal crises of the Italian Socialist Party. A small portion of his analysis regarding Mussolini’s dissent and his defense of entry into the war, and the PSI’s stance of absolute neutrality, is quoted: “Mussolini’s response was that he had undergone an intellectual crisis, since he was a man of action, and his self-evaluation led him to the practical conclusion that a possible intervention in the war had to be considered from a purely national perspective. Sternhell argues that in the period preceding Mussolini’s departure from the Italian party and the founding of the newspaper Il Popolo d’Italia, Mussolini’s thought was dominated by nationalism, a new nationalism. For Mussolini, the inability of the Socialist International stemmed from its refusal to consider the national question. Future socialist critique, he argued, could attempt to find a balancing force between nation and class. This balancing force would be the new form of socialism pioneered by Mussolini, a kind of National Socialism. Sternhell argues that it is important to understand that nationality never led Mussolini to abandon the idea of socialism as a continuous process of social reform. Sternhell argues that “national socialism” is primarily an ideological orientation and political movement, and ended up functioning as a kind of transitional phase in the development of fascism. Perhaps it would be more accurate to say that, since fascism was still nonexistent, such “national socialism” would have been, for Mussolini, a transitional phase in the development of socialism, a possible, albeit theoretically heretical, response“. |

Following the war, Mussolini’s evolution into a fascist leader accelerated as he encountered the social and economic instability of postwar Italy. His ability to assess and exploit political opportunities became evident as he positioned himself as a leader capable of providing stability and national renewal. The development of his oratorical skills during this period proved crucial to his success.

The name “fascism” itself, derived from the Latin word “fasces,” reflects Mussolini’s conscious effort to connect his movement with ancient Roman symbols of authority and power. This etymological choice reveals his understanding that effective political movements require not only ideological coherence but also symbolic resonance with cultural traditions.

| Lessons on Violence Georges Sorel (1847-1922), a French philosopher and theorist of revolutionary syndicalism (another radical leftist), exerted a profound influence on Benito Mussolini during his transition from socialism to fascism in the early 20th century. Mussolini, who began his political career as a socialist editor and activist, encountered Sorel’s writings around 1908–1914, particularly “Reflections on Violence” (1908), which resonated with his growing disillusionment with parliamentary socialism and emphasis on direct action. Sorel’s rejection of rationalist, deterministic Marxism in favor of irrational forces like myth and violence appealed to Mussolini, who saw in them tools for mobilizing the masses beyond class lines toward national renewal. Mussolini openly acknowledged this debt, stating in 1914, “In the whole negative part, we are alike. We both have no faith in parliaments, in democracy, in the people as a decisive factor in politics, in the middle classes. We are alike, even if in different respects, in that we both are enemies of Christianity, of capitalism, of idealism.” He later credited Sorel as his primary intellectual mentor, declaring, “I owe most to Georges Sorel. This master of syndicalism by his rough theories of revolutionary tactics has contributed most to form the discipline, energy and power of the fascist cohorts.“ Sorel’s core ideas, such as the power of myth to inspire heroic action and violence as a moral, regenerative force, directly shaped Mussolini’s fascist ideology. Sorel viewed myths not as falsehoods but as intuitive “bodies of images” that evoke collective sentiments and drive revolutionary change, as he wrote in “Reflections on Violence“: “The general strike is… the myth in which Socialism is wholly comprised, i.e. a body of images capable of evoking instinctively all the feelings which correspond to the different manifestations of the war undertaken by Socialism against modern society.“ He further justified proletarian violence as heroic, stating, “Proletarian violence, carried on as a pure and simple manifestation of the sentiment of class struggle, appears thus as a very fine and very heroic thing; it is at the service of the immemorial interests of civilization; it is not perhaps the most appropriate method of obtaining immediate material advantages, but it may save the world from barbarism.“ Mussolini adapted these concepts by replacing Sorel’s proletarian focus with nationalist myths, such as reviving the Roman Empire, to unify Italians under fascism, and embracing violence through Blackshirt squads to seize power.This influence marked Mussolini’s evolution from internationalist socialism to “national syndicalism,” blending Sorel’s anti-bourgeois, anti-democratic fervor with Italian nationalism. While Sorel remained a syndicalist and never fully endorsed fascism, his emphasis on instinct over intellect and struggle as vital to society provided fascism’s philosophical backbone, enabling Mussolini to justify authoritarianism as a dynamic, mythic force against liberal decay. |

Economic Corporatism and State Control

The economic system under Mussolini’s fascist regime presented a distinct approach to organizing production and labor relations. Italian fascist corporatism emerged as an alternative to free-market capitalism and socialist central planning, promoting a “third way” that preserved private property but under state control. This corporatist system was one of the pillars of Italian fascism, aiming for the “total integration of divergent interests” within state-controlled organizational structures. In practice, despite preaching class collaboration and workers’ representation, fascist corporatism primarily served to strengthen state control over labor and capital while maintaining the appearance of private property.

Mussolini banned Marxist organizations and replaced their unions with government-controlled corporate unions, favoring the interests of large corporations: he reduced taxes for companies, allowed the growth of cartels, decreed wage reductions, and repealed the eight-hour work law.

Mussolini abandoned economic individualism and introduced a state-controlled economy, where “private enterprise controlled production but was supervised by the state,” presenting this as a synthesis that preserved entrepreneurial initiative and guaranteed social coordination.

| Catholic versus fascist corporatism Fascist corporatism and Catholic corporatism both draw from the idea of organizing society into “corporations” or intermediary groups (e.g., guilds, syndicates, or associations representing industries, professions, or classes) to mediate economic and social relations, moving beyond pure individualism or class conflict. However, they differ fundamentally in origins, implementation, philosophy, and goals. Fascist corporatism, as articulated by Benito Mussolini in Italy, was a top-down, state-imposed system designed to consolidate totalitarian power. In contrast, Catholic corporatism, rooted in papal encyclicals like Rerum Novarum (1891) by Pope Leo XIII and Quadragesimo Anno (1931) by Pope Pius XI, emphasizes voluntary associations guided by moral principles, subsidiarity (where higher authorities support but do not supplant lower ones), and social justice aligned with Christian ethics. Below, key difference between them. 1. Role of the State Fascist Corporatism: The state is absolute and totalitarian, claiming supremacy over all aspects of life, including economic ones. Corporations (corporazioni) are state-created organs that coordinate labor, capital, and industries under direct government control, eliminating independent unions or parties. Catholic Corporatism: The state plays a supportive, subsidiary role, intervening only when necessary to aid voluntary associations and ensure the common good. It should not substitute itself for free activity or dominate lower groups. 2. Voluntary vs. Coercive Nature Fascist Corporatism: Mandatory and coercive. Membership in corporations was often compulsory, with the state granting monopolies and forbidding strikes or independent actions. Catholic Corporatism: Voluntary and organic. Associations form naturally based on shared professions or interests, with individuals “quite free to join or not.” 3. Philosophical Foundations and Goals Fascist Corporatism: Rooted in nationalism, anti-liberalism, and anti-socialism, it aims for national power, expansion, and the glorification of the state. The goal is totalitarian unity, often tied to ultra-nationalism and the suppression of dissent. Catholic Corporatism: Grounded in Christian social teaching, it seeks economic justice, the common good, and human flourishing directed toward God. It promotes solidarity, equitable wealth distribution, and protection of workers from exploitation, while rejecting both individualism and collectivism. In summary, fascist corporatism is a tool of state domination and national aggrandizement, while Catholic corporatism is a framework for ethical, voluntary collaboration emphasizing human dignity and subsidiarity. These distinctions highlight why Catholic thinkers often viewed fascist versions as a perversion of the concept. |

Methods of Power and Social Control

The fascist system of social control developed by Mussolini was innovative in its understanding of mass society and the techniques needed to maintain popular support under an authoritarian regime. Unlike traditional dictatorships, which relied on coercion, fascism recognized that a successful regime required public opinion more than outright oppression. Thus, systematic violence was used strategically, not only as repression but also to mobilize supporters through experiences of conflict.

Mussolini adapted his experiences in socialist organizing to mobilize masses behind nationalist goals. Rallies and demonstrations were carefully choreographed to create emotional bonds between leaders and followers, demonstrating popular support. Rather than destroying traditional institutions, fascists captured and redirected them to their own goals, as occurred with the unions transformed into government-controlled “corporatist unions.” Religious and cultural institutions were also co-opted to serve fascist purposes, and large corporations were aligned with government goals in exchange for benefits.

In education and culture, fascism sought to shape popular consciousness in the long term. It attacked intellectual independence and developed its own educational and cultural programs to instill fascist values. The control of cultural and educational production reflected its totalitarian aspirations and the need for cultural hegemony. Sophisticated propaganda, utilizing modern communication technologies, allowed fascists to effectively reach large audiences.

Combining technological capabilities with psychological insights, they created campaigns that appealed to rational and emotional interests, offering simple explanations for complex problems and promising order and national greatness.

Despite rhetoric in favor of social justice, fascist methods of control served to discipline workers and maintain power, revealing the instrumental nature of fascist ideology.

| The expansion of fascists methods of social control in authoritarian governments After Mussolini, many other authoritarian governments employed fascist methods of social control. Below are some of them: China under Xi Jinping (2013–present): The Chinese Communist Party employs the Great Firewall for internet censorship, blocking foreign sites and monitoring online speech via AI-driven surveillance, while the social credit system assigns scores to citizens based on behavior, restricting travel or jobs for “disloyal” individuals—akin to fascist social engineering. Propaganda glorifies Xi as a near-mythical leader, with “Xi Jinping Thought” mandatory in schools. Suppression of Uighurs in Xinjiang involves re-education camps and forced assimilation, justified by nationalist rhetoric against “separatists,” echoing fascist racial and ideological purity campaigns. Russia under Vladimir Putin (2000–present): Putin’s government has consolidated control through state media like RT and Rossiya, which propagate nationalist narratives portraying Russia as besieged by Western “enemies,” fostering a cult of personality around Putin as a strongman defender of the motherland. Opposition figures like Alexei Navalny have been imprisoned, poisoned, or killed, with laws criminalizing “fake news” about the Ukraine war enabling censorship and suppression of dissent. The FSB (successor to the KGB) conducts surveillance, while laws against “foreign agents” target NGOs and independent journalists, mirroring fascist intimidation tactics. Spain under Francisco Franco (1939–1975): After the Spanish Civil War, Franco’s Falange party suppressed opposition through mass executions and imprisonment of republicans, anarchists, and regional nationalists. State-controlled media propagated a cult around Franco as Caudillo (leader), censoring dissent and promoting ultranationalism. Labor unions were banned and replaced with vertical syndicates under state control, while surveillance by the Guardia Civil maintained social order. |

Position in the Circular Diagram of Western Political Mentalities

In the circular arrangement, Radical Statists are positioned adjacent to Radical Leftists (e.g., communism under Stalin or Lenin) and Authoritarian Conservatives (e.g., Franco’s Spain), reflecting shared authoritarian mechanisms like state propaganda and suppression of dissent, despite ideological differences. This adjacency illustrates fluid transitions, such as Mussolini’s evolution from radical leftist to statist, and underscores the diagram’s insight into how extremes converge in totalitarianism, challenging views that place fascism strictly on the “right.” Empirically, this is supported by fascist regimes’ use of state-controlled economies and coercive social order, akin to adjacent groups, while fundamentally clashing with opposite Classical Liberals’ free markets and civil liberties.

Table. Comparison between a capitalist constitutional republic, socialism/communism and fascism, showing how close fascism is to socialism/communism and how far it is from capitalist constitutional republics.

| Characteristic | Capitalist Constitutional Republics | Socialism/ Communism | Fascism |

| Economic System | Market-driven economy with prices set by supply and demand; emphasis on competition and profit motive. | Centrally planned economy, classless society (in practice separation between the ruling class and the rest of the population) | Corporatist economy where private initiative exists, but is heavily regulated and directed by the State to serve the interests of its rulers. |

| Ownership of Means of Production | Private ownership by individuals or corporations. | Collective or state ownership; private property abolished or minimized | Nominal private ownership, but ultimate control and direction by the state; syndicates or corporations aligned with government. |

| Role of Government | Minimal intervention; focuses on protecting property rights, enforcing contracts, and providing public goods like defense. | Extensive control; government plans production, distribution, and owns key industries. | Totalitarian control; government dictates economic policy, suppresses opposition, and mobilizes society for “national goals”. |

| Individual Freedoms | High emphasis on personal liberties, including freedom of speech, assembly, and economic choice. | Limited; prioritizes “collective good” over individual rights, often with censorship and restricted dissent. | Severely restricted; loyalty to the state and leader is paramount, with suppression of free speech and political opposition. |

| Wealth Distribution | Unequal, based on market outcomes; wealth accumulation through innovation and entrepreneurship. | Aimed at equality; redistribution through state mechanisms to eliminate class differences. | Unequal but state-managed; wealth serves national power, with favoritism toward aligned elites and suppression of labor rights. |

| Innovation and Efficiency | Driven by competition and profit incentives; high potential for technological advancement. | Often stifled by central planning; focuses on meeting quotas rather than consumer needs. | Directed toward state priorities like military; can be efficient in mobilization but lacks broad innovation. |

| Political System | Democratic with pluralism; multiple parties and rule of law. | One-party dictatorship. | Authoritarian dictatorship; single-party state with cult of personality and nationalism. |

| Mechanisms for seizing political power | Through democratic elections, peaceful transitions. | Often via revolution, proletarian uprising, or seizure of state apparatus; e.g., Bolshevik Revolution or guerrilla warfare. | Through marches, coups, paramilitary action, or manipulated elections followed by consolidation; e.g., Mussolini’s March on Rome or Hitler’s Enabling Act. |

| Keeping Power Mechanisms | Rule of law, regular elections, checks and balances, media freedom, and civil society oversight ensuring accountability. | One-party dominance, purges, secret police (e.g., KGB), propaganda, and suppression of counter-revolutionaries to maintain control. | Totalitarian apparatus including secret police (e.g., OVRA or Gestapo), cult of personality, pervasive propaganda, and violent elimination of opposition. |

| Social Structure | Class mobility possible through merit; social hierarchies based on wealth and achievement. | Classless society in theory; in practice, party elites form a new hierarchy. | Rigid hierarchy based on loyalty to the regime; emphasis on racial or national purity in some variants. |

| Key Ideological Focus | Individualism, liberty, and free enterprise. God given and natural rights. Equality of all before the law. | Collectivism (supremacy of the State over the individual), economic equality and worker empowerment. Law positivism. | Collectivism (supremacy of the State over the individual), nationalism, militarism. |

| Historical Examples | United States (pre-Roosevelt), Hong Kong (pre-1997), Singapore. | Soviet Union (under Stalin), Cuba, China (under Mao). | Italy under Mussolini, Germany under Hitler. |

Key quotes

- “Everything in the State, nothing outside the State, nothing against the State.”

- From his speech for the Third Anniversary of the March on Rome (October 28, 1925)

- This is perhaps his most famous quote, encapsulating the totalitarian nature of fascism.

- “For the Fascist, everything is the State, and nothing human or spiritual exists, much less has value, outside the State. In this sense Fascism is totalitarian.”

- From “The Doctrine of Fascism” (1932)

- Clearly articulates the absolute primacy of the state over individual existence.

- “The Fascist conception of the State is all-embracing; outside of it no human or spiritual values can exist, much less have value. Thus understood, Fascism is totalitarian, and the Fascist State—a synthesis and a unit inclusive of all values—interprets, develops, and potentates the whole life of a people.”

- From “The Doctrine of Fascism” (1932)

- Elaborates on the totalitarian concept, presenting the state as the embodiment of all values.

- “Democracy is a kingless regime infested by many kings who are sometimes more exclusive, tyrannical and destructive than one, even if he be a tyrant.”

- Reflects his contempt for democratic systems and justification for authoritarian rule.

- “Fascism denies that the majority, by the simple fact that it is a majority, can direct human society; it denies that numbers alone can govern by means of a periodical consultation.”

- From “The Doctrine of Fascism”

- Rejects the fundamental democratic principle of majority rule.

- “The Liberal State is a mask behind which there is no face; it is a scaffold which lacks a building.”

- Expresses his view that liberalism is an empty shell without substance.

- “Let us have a dagger between our teeth, a bomb in our hand, and an infinite scorn in our hearts.”

- Demonstrates his glorification of violence and militant action.

- “Blood alone moves the wheels of history.”

- Reflects his belief in the necessity of violence for historical change.

- “Fascism conceives of life as a struggle in which it behooves a man to win for himself a really worthy place, first of all by fitting himself (physically, morally, intellectually) to become the implement required for winning it.”

- From “The Doctrine of Fascism”

- Articulates the fascist conception of life as constant struggle and competition.

- “The man of Fascism is an individual who is nation and fatherland, which is a moral law, binding together individuals and the generations into a tradition and a mission.”

- From “The Doctrine of Fascism”

- Shows how fascism reconceived the individual as merely a component of the national collective.

- “The Fascist conception of life stresses the importance of the State and accepts the individual only in so far as his interests coincide with those of the State.”

- Clearly subordinates individual rights and interests to those of the state.

The Legacy and Broader Implications

The study of Mussolini’s fascism reveals the continuing importance of understanding political movements not as fixed ideological categories, but as dynamic responses to specific historical conditions and social needs. The temporary success and ultimate failure of fascism provide important lessons about the possibilities and dangers of political movements that promise revolutionary change through authoritarian means while also appealing to popular desires for national greatness and social order. Furthermore, it provides important insights into the dynamics of authoritarian movements and the vulnerabilities of democratic institutions, while the framework of the circle diagram offers valuable tools for understanding how political movements can transcend traditional ideological boundaries while also serving fundamentally antidemocratic purposes.

| The Venezuela Case Venezuela serves as a stark contemporary example of a traditionally democratic country transforming into an authoritarian regime with fascist-tinged methods of social control, despite its official socialist ideology under the Bolivarian Revolution. Once a stable parliamentary democracy with multiparty elections and oil-fueled prosperity since the 1958 Punto Fijo Pact, Venezuela began to decline in 1998 when Hugo Chávez, a socialist former military officer, won the presidency with promises of social reform and an anti-corruption approach. Chávez initially operated within democratic norms but gradually eroded institutions: he rewrote the Constitution in 1999 to expand executive powers, packed the judiciary with supporters, nationalized industries, and used state resources to finance his United Socialist Party of Venezuela (PSUV). By 2005, he controlled the National Assembly, enabling laws like the 2004 media restrictions that shut down opposition channels like RCTV, fostering a cult of personality around himself as a charismatic redeemer. Under Nicolás Maduro, who succeeded Chávez in 2013 amid disputed elections, the regime intensified its authoritarian shift to state radicalism amid economic collapse (hyperinflation exceeding 1 million percent in 2018) and humanitarian crises, including the mass emigration of more than 7.7 million people by 2025. Predictably, Maduro’s government has employed fascist tactics: widespread repression of dissent through the Bolivarian National Intelligence Service (SEBIN) and paramilitary “colectivos,” arbitrary arrests (more than 18,000 political prisoners since 2014), torture, and extrajudicial executions, often justified by labeling opponents as “fascists” or “imperialist agents.” A key tool is the proposed and partially enacted “Law Against Fascism, Neofascism, and Similar Expressions” (enacted in April 2024 and referenced in the 2025 legislation), which vaguely defines “fascism” to criminalize protests, NGO activities, and journalism, imposing up to 30 years in prison for “incitement to hatred” or support for sanctions—ironically used to persecute voices opposing the regime while the government itself demonstrates totalitarian control. The 2024 presidential election exemplified this transformation: opposition candidate Edmundo González Urrutia won with 67% of the vote (according to independent counts from 81% of polling stations), but the regime-controlled National Electoral Council declared Maduro victorious with 51% of the vote, without evidence, triggering massive protests that were met with brutal repression—25 deaths, 2,400 arrests, and internet shutdowns. Maduro’s inauguration on January 10, 2025, boycotted by most international observers and attended only by allies such as Cuba and Nicaragua, cemented his third term amid border closures, preventive detentions, and threats of constitutional reforms to further consolidate power. Additional laws, such as the Simón Bolívar Law of November 2024, allow for the seizure of assets and trials in absentia of “traitors,” while an anti-NGO law (April 2025) freezes foreign funding to civil society, reflecting the fascist erosion of independent institutions. Although it still presents itself as socialist (emphasizing class struggle over fascist nationalism), the Maduro regime shares typical fascist characteristics: a dominant one-party system, state-run media propaganda glorifying the leader and demonizing “enemies” (e.g., the US as imperial fascists), economic corporatism that ties unions to the state, and militarized nationalism to justify repression. In September 2025, international isolation increases—US rewards for Maduro, EU sanctions, and OAS condemnations—but the regime survives through alliances with Russia, China, and Iran, highlighting how crises (economic and electoral) enable such changes in Latin America. |

Questions for reflection

1. How does Mussolini’s transformation from a socialist leader who edited “Avanti” to the creator of fascism through “Il Popolo d’Italia” inform contemporary analyses of political radicalization and the abandonment of democratic principles?

2. How does the Italian corporatist system—where “economics involves labor unions and corporate associations united to collectively represent the nation’s economic producers”—apply to contemporary debates about public-private partnerships and “crony capitalism”?

3. How does Mussolini’s strategy of using violence against “established institutions, socialist politicians, the Catholic Church, the stock market” before World War I inform understandings of contemporary escalation of political violence?

4. What insights does the observation of authoritarian regimes using “data and artificial intelligence to exert surveillance and control at unprecedented levels” offer for understanding differences between historical and contemporary fascism?

5. Reflect on Mussolini’s glorification of violence as a moral and creative force, as seen in quotes like “Blood alone moves the wheels of history”—in what ways might this mindset resonate with contemporary justifications for state-sanctioned force in authoritarian regimes, such as during crackdowns on protests?

6. In what ways does Mussolini’s totalitarian principle—”Everything in the State, nothing outside the State”—challenge individual freedoms, and what lessons can it offer for evaluating surveillance and social control mechanisms in today’s digital authoritarian states like China under Xi Jinping?

7. Reflect on the disillusionment with parliamentary socialism that led Mussolini to embrace fascism; how might this historical pattern shed light on contemporary leftist movements that turn toward more radical alternatives amid perceived failures of democratic socialism?

8. Considering Mussolini’s retention of Marxist revolutionary impulses while rejecting class struggle in favor of national unity, what insights does this provide into the hybrid ideologies of contemporary leaders like those in Venezuela under Maduro, who mix socialism with authoritarian control?

9. The text highlights fascism’s roots in Marxist crises and Sorel’s ideas—how could this connection guide reflections on the potential for ideological disillusionment in current socialist experiments, potentially leading to totalitarian shifts in nations facing economic turmoil?

10. Consider the following decisions of the Brazilian Supreme Court:

Free enterprise (Brazilian Constitution, art. 1, IV and 170, caput) is not an end in itself, but a means to achieve the fundamental objectives of the Republic, including the protection and preservation of the environment for present and future generations (Brazilian Constitution, art. 225) [ADI 6.218, rapporteur Justice Nunes Marques, dissenting opinion by Justice Rosa Weber, judgment of July 3, 2023, Plenary, Official Gazette of August 21, 2023].

The caput of article 52 of Law 13.146/2015, which establishes a quota of vehicles adapted for people with disabilities in rental companies, constitutes a legitimate discipline of the economic order. In this case, no contradiction to the principle of free enterprise is seen, because it concretizes the fundamental rights of personal mobility and access to assistive technology [ADI 5.452, vote of rapporteur Justice Rosa Weber]. [Justice Cármen Lúcia, judgment of August 22, 2020, P, Official Gazette of October 6, 2020.]

Free enterprise is an expression of freedom held not only by businesses but also by labor. Therefore, the Constitution, in contemplating it, also considers the “initiative of the State”; it does not, therefore, privilege it as a good pertinent only to businesses. If, on the one hand, the Constitution ensures free enterprise, on the other hand, it mandates the State to adopt all measures tending to guarantee the effective exercise of the right to education, culture, and sports (articles 23, V; 205; 208; 215; and 217, § 3, of the Constitution). In the composition between these principles and rules, the interest of the community, a primary public interest, must be preserved. The right to access culture, sports, and leisure are means of complementing the education of students. [ADI 1.950, rapporteur Justice Cármen Lúcia] [Eros Grau, judgment of 3-11-2005, Plenary, Official Gazette of 2-6-2006.]

In light of the current Constitution, to reconcile the foundation of free enterprise and the principle of free competition with those of consumer protection and the reduction of social inequalities, in accordance with the dictates of social justice, the State may, through legislation, regulate the pricing policy of goods and services, given the abusive nature of economic power that aims at the arbitrary increase of profits. [ADI 319 QO, rapporteur Justice Moreira Alves, judgment of 3-3-1993, Plenary, Official Gazette of 30-4-1993.]

10.1. Which of the two alternatives seems to make sense to you: “free enterprise is not an end in itself, but a means to achieve the fundamental objectives of the Republic” (that is, the individual, owner of their enterprise, must act seeking the ends of the Republic and, therefore, is a means in the pursuit of the ends of the Republic) or “the right to free enterprise can be restricted when it violates the rights of third parties” (that is, the individual is free to act in pursuit of his ends, but must respect the rights of others)?

10.2. Isn’t the State’s allocation of the use of private property (for example: a quota of vehicles adapted for people with disabilities in rental companies) a partial expropriation of the right to property for social interest?

10.3. What does free enterprise of labor mean? What does free initiative of the State mean?

10.4. What does “economic power aimed at the arbitrary increase of profits” mean? When price increases cease to be at the discretion of the owner of the goods and become at the discretion of the State, isn’t that expropriation?

105. How closely do the aforementioned decisions of the Brazilian Supreme Court resemble fascist ideas?

Leave a comment