Introduction

Alfredo Rocco (1875-1935) was a Neapolitan jurist who became the principal architect of the legal structure of the Italian Fascist regime.

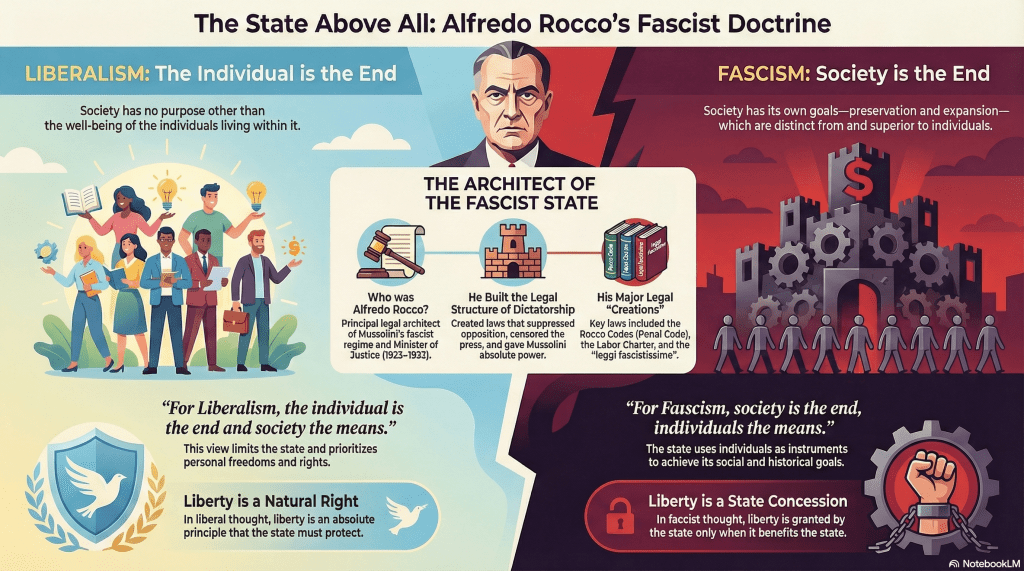

Figure 29. Alfredo Rocco

Source. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Alfredo_Rocco.gif

Rocco was a nationalist before joining fascism. He joined the Italian Nationalist Association (ANI) in 1913, where he became a prominent figure, advocating for nationalist policies and contributing to its congresses in 1914 and 1920.

Although the ANI shared some autoritarian conservative traits—like anti-liberalism, authoritarianism, nationalism, and ties to wealthy elites—it functioned more as a bridge to fascism, hybridizing with radical ideologies and ultimately merging into Mussolini’s National Fascist Party, which underscored its non-conservative radicalism (Some would classify him as a “pseudoconservative,” that is, someone who professes traditional values while harboring subversive impulses).

In fact, it lacked several key elements typically associated with conservatism, such as a commitment to gradual change, preservation of traditional institutions and social hierarchies, moderation in political approach, and avoidance of radical or revolutionary restructuring. Instead, its ideology evolved toward endorsing an authoritarian corporate state, expansionism, and elements of “national socialism,” positioning it as proto-fascism rather than classical conservatism, or even authoritarian conservatism.

The ANI, founded in 1910, was Italy’s first organized nationalist movement and merged with Mussolini’s National Fascist Party in 1923, at which point Rocco transitioned to fascism.

As Mussolini’s Minister of Grace and Justice (1925-1932), Rocco developed a philosophy of legal technicality that transformed law into an instrument of state power, creating the famous Rocco Codes, which profoundly shaped the Italian legal system.

During his ministerial tenure, Rocco was responsible for creating the legal architecture of the fascist regime, including the “leggi fascistissime” of 1925-26,” the Concordato of 1929, the Labor Charter of 1927, the Penal Code and the Code of Criminal Procedure of 1930.

| Fascist laws The “leggi fascistissime,” or “most fascist laws,” were a series of legislative measures enacted between 1925 and 1926, marking the formal transition from a parliamentary system to a full-fledged fascist dictatorship by suppressing political opposition, dissolving non-fascist parties and unions, imposing strict press censorship, granting the Duce (Mussolini) absolute executive powers, and establishing the Grand Council of Fascism as the supreme governing body. These laws—also known as the “exceptional fascist laws”—included the abolition of local elections, the creation of a special tribunal for political crimes, and the requirement of loyalty oaths from public officials, effectively eliminating liberal institutions while bending but not entirely breaking the existing Statuto Albertino constitution. This consolidation of power solidified one-party rule, leading to the removal of dissenting intellectuals and the entrenchment of authoritarian control that defined Italian fascism until its fall in 1943. The Concordato of 1929, also known as the Lateran Concordat, was one of the three key agreements within the Lateran Pacts signed on February 11, 1929, between the Kingdom of Italy under Benito Mussolini and the Holy See under Pope Pius XI, effectively resolving the long-standing “Roman Question” that arose after Italy’s unification in 1870 and the annexation of papal territories. This concordat specifically regulated the relationship between the Catholic Church and the Italian state, granting the Church privileges such as recognition of Catholicism as the state religion, ecclesiastical jurisdiction over marriage, religious education in public schools, and exemptions for clergy from certain civil duties, while in return the Vatican acknowledged Italian sovereignty and agreed to neutrality in international affairs. Accompanied by a treaty establishing Vatican City as an independent sovereign entity and a financial convention providing Italy’s compensation of approximately 750 million lire (plus bonds) for lost papal lands, the pacts solidified Mussolini’s regime by gaining Catholic support and marked a formal reconciliation that endured until revisions in 1984. The Carta del Lavoro (Labor Charter) of 1927 was a fundamental document of the Italian fascist regime that established the principles of Mussolini’s corporatist economic system, declared as a “third way” between capitalism and socialism. Although rhetorically presented as harmony between labor and industry working together for the nation, in practice the Charter abolished the right to strike and made independent unions illegal, establishing that only “legally recognized” unions – that is, fascist ones – could stipulate collective contracts. The resulting corporatist system linked employer and employee unions into corporate associations to collectively represent the nation’s economic producers and work together with the State to define national economic policy, but with all wages determined by the government, mandatory state permission for almost any business activity, and the criminalization of both strikes and lockouts as acts harmful to the national community. The Penal Code and the Code of Criminal Procedure of 1930, collectively known as the Rocco Codes, fundamentally reshaped the Italian legal system to align with Mussolini’s authoritarian regime by replacing the liberal Zanardelli Code of 1889 with a more repressive framework that prioritized state security over individual rights.The Penal Code introduced harsh penalties, including expanded use of the death penalty for political offenses, espionage, and common crimes; it emphasized deterrence, recidivism measures against “veterans of crime,” and “security measures” for socially dangerous individuals, while structuring offenses to place crimes against the state’s personality and security first, reflecting fascist ideology’s subordination of personal freedoms to national interests. Complementing this, the Code of Criminal Procedure established an inquisitorial model with secretive investigations, limited defense participation (e.g., no counsel presence in early stages until 1955 amendments), and empowered prosecutors and police in evidence gathering, enabling suppression of opposition while maintaining a facade of legality; though amended post-World War II to remove overtly fascist elements, these codes influenced Italy’s criminal justice until a new procedural code in 1988. |

Legal Philosophy and Corporatist Ideology

Rocco was one of the leading theorists of fascist corporatism, developing an ideology that sought to harmonize relations between social classes through state control. corporatist vision conceived of the state as the supreme mediator between employers and employees, creating a system where all economic activities were comprehensively supervised by the government. This philosophy rejected both liberalism and Marxism, proposing a “third way” in which the state directed the economy through sectoral corporations.

Alfredo Rocco’s 1926 essay “The Political Doctrine of Fascism” (originally a speech) serves as a foundational ideological text for Italian Fascism, endorsed by Benito Mussolini as a masterful exposition of its principles. The work critiques modern liberal, democratic, and socialist doctrines while articulating Fascism as a coherent alternative rooted in an organic, state-centric view of society.

The Political Doctrine of Fascism

The essay is structured around several interconnected themes: the nature of Fascism as action, sentiment, and thought; the shared flaws in prevailing political ideologies; Fascism’s contrasting organic conception of society; and its implications for liberty, government, social justice, and historical significance. Rocco positions Fascism not just as a political movement but as a comprehensive philosophy with universal applicability, drawing on Italian intellectual traditions while rejecting foreign influences.

Its main arguments and critics are:

- Fascism as a Complete Doctrine: Rocco asserts that Fascism encompasses action (practical implementation), feeling (national and racial instinct), and thought (theoretical principles). Its rapid success in Italy and beyond stems from this integrated doctrine, which provides a clear guiding concept lacking in opposition parties. He emphasizes Fascism’s Italian origins but claims its principles hold broader validity.

- Critique of Atomistic Ideologies (Liberalism, Democracy, and Socialism): Rocco traces these doctrines to common roots in the Protestant Reformation and natural law theories of the 17th-18th centuries. He condemns them as “atomistic” and “mechanical,” viewing society merely as an aggregate of individuals focused on present-generation welfare. This perspective is anti-historical (ignoring societal continuity across generations), materialistic (prioritizing economic over spiritual values), and individualistic (subordinating society to personal ends).

- Liberalism: Limits the state to coordinating individual liberties, leading to weakened governance through checks like separation of powers and failing to address social inequalities.

- Democracy: Extends Liberalism by vesting sovereignty in the people, promoting equality but enabling the masses to prioritize private over collective interests.

- Socialism (and Bolshevism): Seeks collective production to remedy capitalist exploitation but paralyzes economy by suppressing individual initiative, ignoring human nature, and dispersing capital.

- Fascism’s Organic and Historic View of Society: In contrast, Fascism conceives society as an organic entity—a “fraction of the human species” with perpetual life transcending individuals. Society has its own historical ends (preservation, expansion, power), which may require individual sacrifice. This inverts the liberal formula: “society for the individual” becomes “individuals for society,” with the state as the supreme authority. Individuals are means to social ends, and their rights exist only insofar as they align with state interests, emphasizing duty over liberty.

- Implications for Liberty, Government, and Social Justice:

- Liberty: Not an absolute principle but a concession from the state, promoting individual development only for societal benefit. Economic liberty is a tool for social utility, not individual gain.

- Government: Rejects popular sovereignty in favor of state sovereignty, governed by an elite capable of transcending personal interests. The masses can influence in crises but lack the vision for long-term societal goals.

- Social Justice: Acknowledges class conflicts but rejects socialist collectivization. Instead, Fascism advocates state-controlled syndicalism (trade unions as legal entities), transforming class self-defense into state-mediated justice to ensure production and equity without paralyzing the economy.

Key quotes

“For Liberalism, society has no purposes other than those of the members living at a given moment.“

“For Fascism, society has historical and immanent ends of preservation, expansion, improvement, quite distinct from those of the individuals which at a given moment compose it; so distinct in fact that they may be in opposition.”

“Instead of the liberal-democratic formula, ‘society for the individual,’ we have, ‘individuals for society.“

“For Liberalism, the individual is the end and society the means; nor is it conceivable that the individual, considered in the dignity of an ultimate finality, be lowered to mere instrumentality. For Fascism, society is the end, individuals the means, and its whole life consists in using individuals as instruments for its social ends.”

“Our concept of liberty is that the individual must be allowed to develop his personality in behalf of the state, for these ephemeral and infinitesimal elements of the complex and permanent life of society determine by their normal growth the development of the state.”

“Fascism does not look upon the doctrine of economic liberty as an absolute dogma. It does not refer economic problems to individual needs, to individual interest, to individual solutions.“

“The state is the sole repository of sovereignty and hence of political legitimacy. But the state, in its turn, receives its impulse and orientation from a minority, from an aristocracy, from an élite.“

“Fascism therefore opposed the socialist program but not socialism as such, which, on the contrary, it incorporated within itself, giving it a new lease of life.”

“The true antithesis, not to this or that manifestation of the liberal-democratic-socialistic conception of the state but to the concept itself, is to be found in the doctrine of Fascism.“

“Fascism replaces therefore the old atomistic and mechanical state theory which was at the basis of the liberal and democratic doctrines with an organic and historic concept.”

Alfredo Rocco’s Classification in the Circular Diagram of Western Political Mentalities

Alfredo Rocco (1875–1935), as a fascist, an extreme form of authoritarian statism, clearly fits into the Radical Statist category in the circular diagram of Western political mentalities. Rocco’s classification among the radical statists is confirmed by the fact that fascist corporatism represented a government-directed system that aimed to oversee production comprehensively.

In the diagram’s circular arrangement, Radical Statists are adjacent to Authoritarian Conservatives (sharing authoritarianism and militarism) and Radical Leftists (sharing revolutionary control and violence), which reflects Rocco’s nationalist roots and the fascist regime’s overlaps with both conservative hierarchy and leftist collectivism—evident in Mussolini’s own shift from socialism to fascism.

Rocco’s rejection of liberalism, democracy, and socialism positions him in direct opposition to Classical Liberals (who emphasize individual freedoms and limited government), consistent with the diagram’s oppositional dynamics.

Rocco’s shift from nationalist (a proto-fascist, with some authoritarian conservative elements) to fascist (as many other proto-fascists, and even some authoritarian conservatives did in fascist Italy), joining Mussolini, a socialist (a radical leftist) who became a fascist (as many radical socialists did in fascist Italy), encountering and forming fascism, is a relevant example of the explanatory power and usefulness of the circular diagram of Western political mentalities.

| Shared Characteristics Between Antifascists and Fascists Neurological evidence from Brown University creveals that “the brains of highly conservative and highly liberal individuals are processing the same charged political content in ways that are even more similar than people in their own political parties with more moderate beliefs.” (https://www.brown.edu/news/2025-08-28/extremist-brains) Both movements share authoritarian psychological structures and Manichean views of the political world. Extremists on both spectrums exhibit “prejudice against those who are different, the willingness to exercise authority within a social group to coerce individuals’ behavior, cognitive rigidity, aggression and punishment toward enemies perceived as different” (https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/psychology/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2025.1627540/full) Ideologically extreme individuals “not only adopt a cognitive “us versus them” worldview but also exhibit pronounced affective and behavioral hostility toward political opponents.” (https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/political-science-research-and-methods/article/nonlinearity-between-populist-attitudes-and-ideological-extremism/67739FA295B84B9FF1C973D24F8A1369) The most significant convergence occurs in tactical methods and a willingness to abandon democratic norms. For example, some modern anti-fascist movements involve digital activism, harassment, physical violence, and property damage, mirroring the tactics historically employed by fascists. Extremes on both spectrums share a willingness to “break the system” and abandon democratic discourse, sharing authoritarian preferences and posing functionally similar threats to democratic stability, regardless of their seemingly opposing ideological motivations. |

The Contemporary Relevance of Alfredo Rocco’s Ideas

Although Rocco’s ideas are largely marginalized in democratic societies, seen as relics of a discredited totalitarianism, they remain important as a historical reference. The clarity of Rocco’s exposition of fascism and his central opposition to classical liberalism (individualism, individual liberties, divine rights, natural rights) make his work worthy of reading to this day.

| Similarities between the fascist Rocco Codes, the Communist USSR Penal Code (1926), and the Communist People’s Republic of China Penal Code (1979). All three codes served as tools for regime consolidation in authoritarian systems, sharing: State Prioritization: Crimes against the state (e.g., subversion, propaganda) are prioritized, reflecting totalitarian control. Rocco’s “state personality” mirrors Soviet Article 58 and Chinese counterrevolutionary chapters. Repressive Flexibility: Vague or analogical provisions allowed broad application against dissent—Rocco’s ambiguity, early Soviet/Chinese analogy. Increased Sentences and the Death Penalty for Political Crimes: All reinstated or emphasized severe punishments, including capital punishment for political crimes, rejecting liberal leniency. Ideological Rejection of Liberalism: Each code broke with pre-regime liberal laws, using criminal law to impose ideologies (fascism, communism, socialism). In short, these codes exemplify how authoritarian regimes use criminal law as a weapon for ideological application, with shared repressive tools but with distinct characteristics: nationalist in Italy, class-based in the USSR, and state socialist in China. |

Questions for reflection

1. How does Rocco’s view of the state as an “organic entity” with its own perpetual goals challenge modern liberal notions of individual sovereignty, and could this perspective justify increased government surveillance in the name of national security today?

2. In what ways might Rocco’s subordination of individual rights to collective duties resonate with contemporary debates on mandatory public health measures, such as vaccine mandates during global pandemics?

3. Considering Rocco’s emphasis on elite rule over mass sovereignty, how does this align or conflict with the rise of populist leaders like those in recent elections in Europe or the Americas, who claim to represent “the people” against elites?

4. Rocco’s corporatist economic model integrated labor into the state—could elements of this be seen in modern “state capitalism” practices in countries like China, where private enterprise serves national interests?

5. How does Rocco’s prioritization of duty over liberty parallel contemporary discussions on “cancel culture” or social conformity, where group norms enforce behaviors at the expense of personal freedoms?

6. To what extent does Rocco’s corporatist model, where the state mediates between employers and employees, fundamentally differ from the systems of tripartite social dialogue in current European democracies?

7. How did Rocco’s legal codes, which subordinated individual rights to state interest, anticipate contemporary debates about anti-terrorism legislation and emergency powers?

8. Do organizations like the European Union, with their sectoral representation and corporate governance, represent a democratic evolution of Rocco’s corporatist ideas or a continuation of his authoritarian principles?

Leave a comment