Introduction: Historical and philosophical context

Aristotle, born in Stagira, Greece, was a student of Plato and tutor to Alexander the Great. His Politics, written around 350 BC, is a seminal treatise on political organization, exploring how different systems of government can promote the common good or fail due to corruption. He saw politics as the most authoritative science, aiming at human good, especially happiness, which is achieved in community.

Figure 7. Bust of Aristotle.

Author: Roman marble copy of the bronze original by Lysippos (330 BC); the alabaster robe is a modern addition. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Aristotle_Altemps_Inv8575.jpg

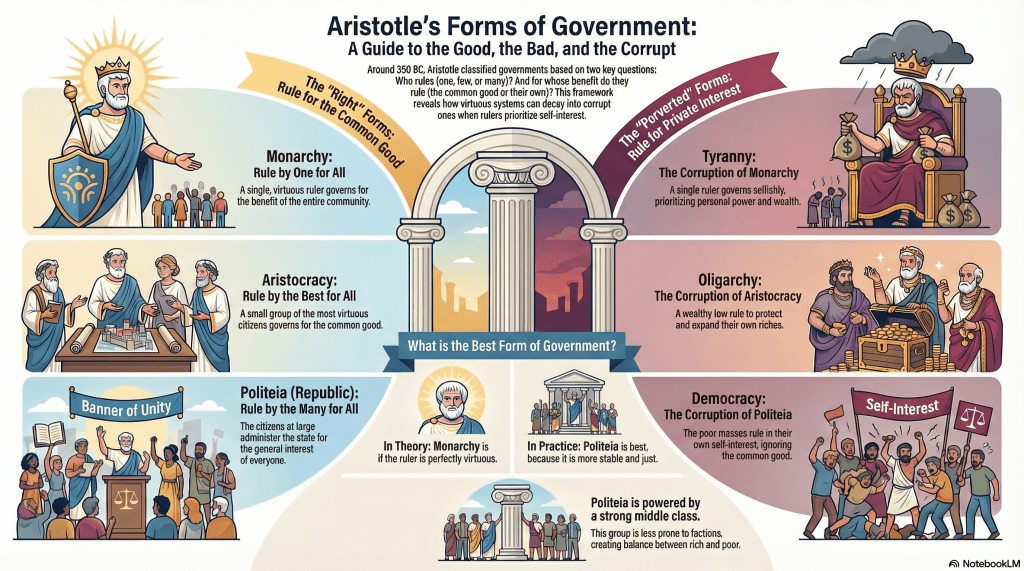

Aristotle’s Classification of Forms of Government

Aristotle classifies governments based on two criteria: the number of rulers (one, a few, or many) and the purpose of government (common interest or private interest).

- Right forms: Rule for the common good.

- Monarchy (Royalty): A wise ruler rules for all.

- Aristocracy: A few, the best, rule virtuously.

- Politeia (Republic): Many citizens rule for the general interest.

- Perverted forms: Rule for private interest.

- Tyranny: Selfish monarch, perversion of monarchy.

- Oligarchy: Rich people rule for themselves, perversion of aristocracy.

- Democracy: Mass rules for self-interest, perversion of politeia.

This distinction is based on the concept that correct regimes aim for the common good, while perverted ones prioritize the rulers.

| Nicaragua’s [degenerated] democracy. José Daniel Ortega Saavedra (1945) is a Nicaraguan politician. He was the leader of the Sandinista National Liberation Front (FSLN), Nicaragua’s socialist party, and president of Nicaragua from 1985 to 1990 and from 2007 to 2025. He is currently co-president of Nicaragua since 18 February 2025, alongside his wife, Rosario Murillo. His government is characterized by maintaining democratic facades, but substantive democratic practices are absent. The regime’s control over institutions, electoral manipulation, constitutional amendments for indefinite reelection, capture of the judiciary, shutdown of the media, repression of protests, murder of demonstrators, arrest and deportation of political prisoners, and revocation of citizenship of its opponents have created a climate of fear and instability. The repression has led to a significant exodus, with approximately 600,000 Nicaraguans fleeing in recent years, with more than 30,000 registered in Costa Rica. This mass migration underscores the gravity of the situation, with many seeking refuge from the political turmoil. International bodies such as the UN, US, EU, and OAS have imposed sanctions and denounced the regime, but these measures have had little impact. Despite these challenges, Ortega’s grip on power remains firm, with no immediate signs of reversal. |

Although this classification is based on the number of rulers, Aristotle himself clarifies that the number of rulers is accidental in oligarchies (a few rule) and democracies (many rule), due to the fact that the rich are few and the poor are many everywhere. The real distinction between democracy and oligarchy is that in oligarchies the rulers owe their power to wealth, whether they are a minority or a majority, while in democracy, power is held by the poor (who are always many).

Degeneration of Forms of Government

Aristotle argues that every correct form can degenerate into its perverse form when rulers prioritize self-interest, corruption or lack of virtue.

- From Monarchy to Tyranny:

- Monarchy degenerates into tyranny when the king seeks personal power. This occurs due to the corruption of virtue, leading to oppression.

- From Aristocracy to Oligarchy:

- Aristocracy becomes oligarchy when rulers, initially virtuous, begin to prioritize wealth. This results in inequality and social discontent.

- From Politeia to Democracy:

- Politeia degenerates into democracy when the people rule for their own interests, leading to chaos, ignoring minorities, and leading to impulsive decisions.

| The Russian Oligarchy A prominent modern example of oligarchy, as Aristotle’s degenerate form of aristocracy, is Russia under Vladimir Putin. In Aristotle’s terms, aristocracy is rule by a virtuous few for the common good, but it degenerates into oligarchy when the wealthy few govern solely for their own enrichment, exploiting power to maintain inequality and suppress dissent, often regardless of the number but defined by wealth over virtue.Russia exemplifies this: Since the 1990s post-Soviet privatization, a small group of billionaire “oligarchs”—wealthy individuals with ties to politics and key industries like energy and metals—has wielded disproportionate influence alongside Putin, who has centralized power since 2000. This elite rules not for the common good but for personal and group interests, as seen in crony capitalism where oligarchs control vast resources, often gaining favors through loyalty to the regime. Putin, while appearing as a strongman (echoing tyranny), operates within an oligarchic system where decisions prioritize the rich’s wealth preservation—e.g., sanctions evasion benefits elites while ordinary Russians face economic hardship and suppressed freedoms. This causes social discontent, as Aristotle predicted, with inequality (Russia’s Gini coefficient around 0.37) and corruption (ranking 141/180 on Transparency International’s index) eroding public welfare. Degeneration occurred post-1991, when initial reforms aimed at broader prosperity corrupted into elite capture, aligning with Aristotle’s view that oligarchy arises when rulers prioritize wealth over virtue, leading to instability (e.g., protests like those in 2011–2012 or Navalny’s opposition, which was crushed). Unlike a true aristocracy, Russia’s system lacks focus on the best for all, instead fostering a “few” defined by riches and loyalty, making it a textbook oligarchy in Aristotle’s sense. |

Aristotle suggests that degeneration is natural without virtue, law, and education, and proposes a mixed constitution to prevent this.

Table: Classification and Degeneration of Forms of Government

| Correct Form | Description | Perverted Form | Description |

| Monarchy (Royalty) | One rules for the common good | Tyranny | Monarch rules for himself |

| Aristocracy | A virtuous few rule for all | Oligarchy | The rich rule for their own benefit |

| Politeia (Republic) | Many rule for the general interest | Democracy | Mass rules for self-interest, not common interest |

The Best Form of Government: Theory and Practice

Aristotle considered monarchy to be the best form of government in theory, but in practice he preferred politeia:

- Monarchy in theory: For Aristotle, under ideal conditions, monarchy is preferable, especially when there is an individual or family of supreme excellence. He argues that a virtuous ruler can perfectly align himself with the common good, promoting the happiness of all citizens. However, he acknowledges that such a situation is rare, and the risk of degeneration into tyranny is high

- Politeia in practice: In practice, Aristotle favored politeia, a mixed constitution controlled by the middle class, as being more stable and just. He characterizes politeia as a “mixed” regime, typified by the rule of the middle class of citizens, moderately wealthy, between the rich and the poor. Politeia is presented as an alternative to a more stable constitution, where ordinary people can live better in intersubjective relations with virtuous people. The reason for preferring politeia in practice is that the middle class is less prone to factions and injustices, promoting balance. It combines elements of oligarchy (elected offices) and democracy (offices without evaluation), offering stability. There is controversy over which form Aristotle actually considered best. Some authors argue that he was cautiously in favor of democracy but warned of its fragility, while others suggest that aristocracy can also be ideal in theory, especially when the rulers are virtuous. However, the evidence points to politeia as the practical choice, reflecting debates about stability versus idealism that are still present today.

Table: Comparison of Monarchy and Politeia as Better Forms

| Aspect | Monarchy (Theoretical) | Politeia (Practical) |

| Definition | Government of one, virtuous, for the common good | Mixed constitution, ruled by the middle class |

| Advantages | Aligns perfectly with the common good | Stable, reduces factionalism, promotes justice |

| Challenges | Rare to find a virtuous ruler, risk of tyranny | Depends on social balance, may degenerate |

Conclusion

Aristotle’s classification of forms of government and his analysis of degeneration provide a timeless framework for understanding political systems. His emphasis on virtue and the common good highlights the need for balance to avoid corruption, with insights relevant to modern political discourse.

Furthermore, Aristotle considered monarchy the best form of government in theory, but in practice he preferred politeia for its stability and balance. This distinction reflects his practical approach, recognizing the rarity of virtuous rulers and the need for systems that promote the common good in real-world conditions. The controversies over his preference highlight timeless debates about idealism and pragmatism in political philosophy.

Key Points

- Aristotle classified governments into six forms: three virtuous (monarchy, aristocracy, politeia) and three perverted (tyranny, oligarchy, democracy), based on who rules and for whose benefit.

- According to him, virtuous forms degenerated into their perverse form due to self-interest, corruption or lack of virtue.

- Furthermore, the best form of government, from a practical point of view, would be politeia.

Selected excerpts

Aristotle. Politics. Translated by Benjamin Jowett. Kitchener. 1999. (https://historyofeconomicthought.mcmaster.ca/aristotle/Politics.pdf)

Part VI

Having determined these questions, we have next to consider whether there is only one form of government or many, and if many, what they are, and how many, and what are the differences between them.

A constitution is the arrangement of magistracies in a state, especially of the highest of all. The government is everywhere sovereign in the state, and the constitution is in fact the government. For example, in democracies the people are supreme, but in oligarchies, the few; and, therefore, we say that these two forms of government also are different: and so in other cases.

First, let us consider what is the purpose of a state, and how many forms of government there are by which human society is regulated. We have already said, in the first part of this treatise, when discussing household management and the rule of a master, that man is by nature a political animal. And therefore, men, even when they do not require one another’s help, desire to live together; not but that they are also brought together by their common interests in proportion as they severally attain

to any measure of well-being. This is certainly the chief end, both of individuals and of states. And also for the sake of mere life (in which there is possibly some noble element so long as the evils of existence do not greatly overbalance the good) mankind meet together and maintain the political community. And we all see that men cling to life even at the cost of enduring great misfortune, seeming to find in life a natural sweetness and happiness.

There is no difficulty in distinguishing the various kinds of authority; they have been often defined already in discussions outside the school. The rule of a master, although the slave by nature and the master by nature have in reality the same interests, is nevertheless exercised primarily with a view to the interest of the master, but accidentally considers the slave, since, if the slave perish, the rule of the master perishes with him. On the other hand, the government of a wife and children and of a household, which we have called household management, is exercised in the first instance for the good of the governed or for the common good of both parties, but essentially for the good of the governed, as we see to be the case in medicine, gymnastic, and the arts in general, which are only accidentally concerned with the good of the artists themselves. For there is no reason why the trainer may not sometimes practice gymnastics, and the helmsman is always one of the crew. The trainer or the helmsman considers the good of those committed to his care. But, when he is one of the persons taken care of, he accidentally participates in the advantage, for the helmsman is also a sailor, and the trainer becomes one of those in training. And so in politics: when the state is framed upon the principle of equality and likeness, the citizens think that they ought to hold office by turns. Formerly, as is natural, every one would take his turn of service; and then again, somebody else would look after his interest, just as he, while in office, had looked after theirs. But nowadays, for the sake of the advantage which is to be gained from the public revenues and from office, men want to be always in office.

One might imagine that the rulers, being sickly, were only kept in health while they continued in office; in that case we may be sure that they would be hunting after places. The conclusion is evident: that governments which have a regard to the common interest are constituted in accordance with strict principles of justice, and are therefore true forms; but those which regard only the interest of the rulers are all defective and perverted forms, for they are despotic, whereas a state is a community of freemen.

Part VII

Having determined these points, we have next to consider how many forms of government there are, and what they are; and in the first place what are the true forms, for when they are determined the perversions of them will at once be apparent. The words constitution and government have the same meaning, and the government, which is the supreme authority in states, must be in the hands of one, or of a few, or of the many. The true forms of government, therefore, are those in which the one, or the few, or the many, govern with a view to the common interest; but governments which rule with a view to the private interest, whether of the one or of the few, or of the many, are perversions. For the members of a state, if they are truly citizens, ought to participate in its advantages. Of forms of government in which one rules, we call that which regards the common interests, kingship or royalty; that in which more than one, but not many, rule, aristocracy; and it is so called, either because the rulers are the best men, or because they have at heart the best interests of the state and of the citizens. But when the citizens at large administer the state for the common interest, the government is called by the generic name—a constitution. And there is a reason for this use of language. One man or a few may excel in virtue; but as the number increases it becomes more difficult for them to attain perfection in every kind of virtue, though they may in military virtue, for this is found in the masses. Hence in a constitutional government the fighting-men have the supreme power, and those who possess arms are the citizens.

Of the above-mentioned forms, the perversions are as follows: of royalty, tyranny; of aristocracy, oligarchy; of constitutional government, democracy. For tyranny is a kind of monarchy which has in view the interest of the monarch only; oligarchy has in view the interest of the wealthy; democracy, of the needy: none of them the common good of all.

Part VIII

But there are difficulties about these forms of government, and it will therefore be necessary to state a little more at length the nature of each of them. For he who would make a philosophical study of the various sciences, and does not regard practice only, ought not to overlook or omit anything, but to set forth the truth in every particular. Tyranny, as I was saying, is monarchy exercising the rule of a master over the political society; oligarchy is when men of property have the government in their hands; democracy, the opposite, when the indigent, and not the men of property, are the rulers. And here arises the first of our difficulties, and it relates to the distinction drawn. For democracy is said to be the government of the many. But what if the many are men of property and have the power in their hands? In like manner oligarchy is said to be the government of the few; but what if the poor are fewer than the rich, and have the power in their hands because they are stronger? In these

cases the distinction which we have drawn between these different forms of government would no longer hold good.

Suppose, once more, that we add wealth to the few and poverty to the many, and name the governments accordingly—an oligarchy is said to be that in which the few and the wealthy, and a democracy that in which the many and the poor are the rulers—there will still be a difficulty. For, if the only forms of government are the ones already mentioned, how shall we describe those other governments also just mentioned by us, in which the rich are the more numerous and the poor are

the fewer, and both govern in their respective states?

The argument seems to show that, whether in oligarchies or in democracies, the number of the governing body, whether the greater number, as in a democracy, or the smaller number, as in an oligarchy, is an accident due to the fact that the rich everywhere are few, and the poor numerous. But if so, there is a misapprehension of the causes of the difference between them. For the real difference between democracy and oligarchy is poverty and wealth. Wherever men rule by reason of their wealth, whether they be few or many, that is an oligarchy, and where the poor rule, that is a democracy. But as a fact the rich are few and the poor many; for few are well-to-do, whereas freedom is enjoyed by an, and wealth and freedom are the grounds on which the oligarchical and democratical parties respectively claim power in the state.

Part IX

Let us begin by considering the common definitions of oligarchy and democracy, and what is justice oligarchical and democratical. For all men cling to justice of some kind, but their conceptions are imperfect and they do not express the whole idea. For example, justice is thought by them to be, and is, equality, not. however, for however, for but only for equals. And inequality is thought to be, and is, justice; neither is this for all, but only for unequals. When the persons are omitted, then men judge erroneously. The reason is that they are passing judgment on them-selves, and most people are bad judges in their own case. And whereas justice implies a relation to persons as well as to things, and a just distribution, as I have already said in the Ethics, implies the same ratio between the persons and between the things, they agree about the equality of the things, but dispute about the equality of the persons, chiefly for the reason which I have just given—because they are bad judges in their own affairs; and secondly, because both the parties to the argument are speaking of a limited and partial justice, but imagine themselves to be speaking of absolute justice. For the one party, if they are

unequal in one respect, for example wealth, consider themselves to be unequal in all; and the other party, if they are equal in one respect, for example free birth, consider themselves to be equal in all. But they leave out the capital point. For if men met and associated out of regard to wealth only, their share in the state would be proportioned to their property, and the oligarchical doctrine would then seem to carry the day. It would not be just that he who paid one mina should have the same share of a hundred minae, whether of the principal or of the profits, as he who paid the remaining ninety-nine. But a state exists for the sake of a good life, and not for the sake of life only: if life only were the object, slaves and brute animals might form a state, but they cannot, for they have no share in happiness or in a life of free choice. Nor does a state exist for the sake of alliance and security from injustice, nor yet for the sake of exchange and mutual intercourse; for then the Tyrrhenians and the Carthaginians, and all who have commercial treaties with one another, would be the citizens of one state. True, they have agreements about imports, and engagements that they will do no wrong to one another, and written articles of alliance. But there are no magistrates common to the contracting parties who will enforce their engagements; different states have each their own magistracies. Nor does one state take care that the citizens of the other are such as they ought to be, nor see that those who come under the terms of the treaty do no wrong or wickedness at an, but only that they do no injustice to one another. Whereas, those who care for good government take into consideration virtue and vice in states. Whence it may be further inferred that virtue must be the care of a state which is truly so called, and not merely enjoys the name: for without this end the community becomes a mere alliance which differs only in place from alliances of which the members live apart; and law is only a convention, ‘a surety to one another of justice,’ as the sophist Lycophron says, and has no real power to make the citizens.

This is obvious; for suppose distinct places, such as Corinth and Megara, to be brought together so that their walls touched, still they would not be one city, not even if the citizens had the right to intermarry, which is one of the rights peculiarly characteristic of states. Again, if men dwelt at a distance from one another, but not so far off as to have no intercourse, and there were laws among them that they should not wrong each other in their exchanges, neither would this be a state. Let us suppose that one man is a carpenter, another a husbandman, another a shoemaker, and so on, and that their number is ten thousand: nevertheless, if they have nothing in common but exchange, alliance, and the like, that would not constitute a state. Why is this? Surely not because they are at a distance from one another: for even supposing that such a community were to meet in one place, but that each man had a house of his own, which was in a manner his state, and that they made alliance with one another, but only against evil-doers; still an accurate thinker would not deem this to be a state, if their intercourse with one another was of the same character after as before their union. It is clear then that a state is not a mere society, having a common place, established for the prevention of mutual crime and for the sake of exchange. These are conditions without which a state cannot exist; but all of them together do not constitute a state, which is a community of families and aggregations of families in well-being, for the sake of a perfect and self-sufficing life. Such a community can only be established among those who live in the same place and intermarry. Hence arise in cities family connections, brotherhoods, common sacrifices, amusements which draw men together. But these are created by friendship, for the will to live together is friendship. The end of the state is the good life, and these are the means towards it. And the state is the union of families and villages in a perfect and self-sufficing life, by which we mean a happy and honorable life.

Our conclusion, then, is that political society exists for the sake of noble actions, and not of mere companionship. Hence they who contribute most to such a society have a greater share in it than those who have the same or a greater freedom or nobility of birth but are inferior to them in political virtue; or than those who exceed them in wealth but are surpassed by them in virtue.

From what has been said it will be clearly seen that all the partisans of different forms of government speak of a part of justice only.

Questions for reflection:

1. Is the meaning given by Aristotle to the word democracy, government of the poor, the same meaning adopted today? Is the term used with the same meaning by all political groups? Or, what does the left understand as democracy? What does the right understand as democracy?

2. Review the table The degenerate democracy of Nicaragua. In your opinion, is this a good example of what Aristotle described as democracy (degenerate politéia)? How and why did this degeneration occur? Or, in other words, how did the socialist Ortega, with a discourse of serving the poor (socialist), transform Nicaraguan democracy into a degenerate government oriented towards serving his faction?

3. What would be the proposals for public policies, nowadays, that are characteristic of a government for the poor? Do such policies contribute to the construction of a virtuous society? Is the result of these policies the common good?

4. To what extent is a government for the poor a degenerate government?

5. How can governments be prevented from degenerating?

6. Which government today most resembles what Aristotle calls politeia?

7. What would a government for the common good be?

8. How can we make rulers govern for the common good? So that their citizens can have a good life.

| In which form of government, according to Aristotle, would you classify Brazil? Some information about Brazil (research more before answering the question) In Brazil, the judiciary operates as a vast and bureaucratic institution, boasting one of the world’s largest contingents of judges (around 16,000) and lawyers, yet it ranks among the least efficient globally, with civil justice delays averaging 600 days in first-instance courts—nearly three times the European average of 232 days. It scores poorly on international metrics, such as 78th out of 143 in the World Justice Project’s Rule of Law Index and 138th out of 139 for criminal justice impartiality, reflecting issues like backlog, opacity, and perceived bias. Critics argue that this system sometimes oversteps constitutional boundaries, prioritizing institutional and political interests. The economy features significant oligopolistic control in key sectors, bolstered by government policies that have historically favored large corporations through the Brazilian Development Bank (BNDES), which provides subsidized loans and equity investments via subsidiaries like BNDESPar. Under past administrations, this included promoting “national champions” in industries like agribusiness, often at the expense of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), which face barriers despite constitutional mandates for preferential treatment. Brazil’s governance exhibits elements of corporatism, where the federal government maintains close ties with powerful unions and corporations, fostering a system that can lead to favoritism, nepotism, and regulatory rigidities. This dynamic, rooted in historical state intervention, prioritizes organized interests, though labor reforms in recent years have aimed to liberalize markets. A core feature of Brazilian policy is its emphasis on aiding the poorest through programs like Bolsa Família, a conditional cash transfer initiative that has significantly reduced poverty and inequality by providing minimum income to millions, while stimulating local economies. Funded primarily through general taxation—including regressive indirect taxes that disproportionately burden the middle class—these efforts are financed by broader revenue streams, raising debates about equity and long-term sustainability. |

Leave a reply to fearlesse6315fa66c Cancel reply